Beyoncé, Western Lit, and the Cowboy Renaissance

Growing up in Nashville, I’d always hated country music, as did a lot of other Black people. At least, that’s how it felt to me at the time. This may sound odd to someone not from there since it is literally the country music capital of the world — a title that was leaned into. Every other radio station played country exclusively, and trips to the Grand Ole Opry were always a thing. Despite this and the fact that Black people have had a big part in developing country music in the first place, I still greatly disliked the genre.

But why the disconnect? For one, I hadn’t learned about Black folks’ deep ties to the genre until much later — which is a gag because banjoes, thee country music instruments, are from West Africa. I think this was by design. Like with many other aspects of American culture and history, non-white people had been written out of country music. And even though I was young, I — like I imagine the other Black kids who didn’t like country music — knew early on to associate the genre with people who weren’t friendly to people who looked like me. There was a subtext to people who declared their love for country music. Their favorite songs spoke of “redneck values,” they didn’t mind donning the confederate flag, and some of their fave musical groups had names that celebrated the antebellum south.

This was all, again, despite the connection to the genre that Black people had. In the past few years, I’ve started to see a shift, though. There were always Black country artists, of course, but it was only in the last few years that I’ve seen mainstream Black artists being tied to the genre and its iconography. Just a few years ago, Lil Nas X burst onto the scene with a song that started out as a meme (but was still, legitimately, a bop) and shook up the country music world a bit. Suddenly, with “Old Town Road,” I was seeing this adorable Black kid boppin’ and smiling to a beat with a country-esque accent and cowboy garb. He even had Billy Ray Cyrus on the remix.

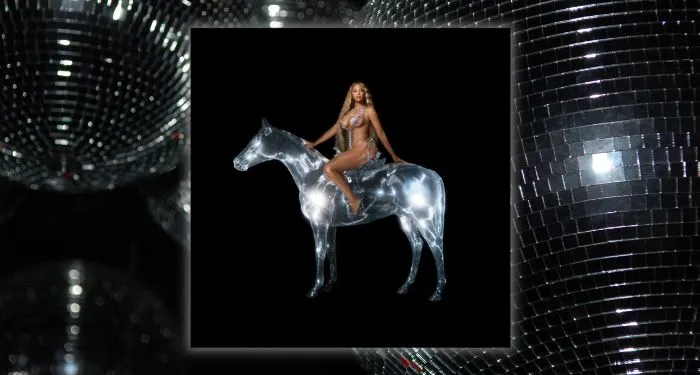

Lil Nas X wasn’t the only one. Beyoncé, and her sister Solange, had always repped their Texas roots, but it wasn’t until the last few years that I’d seen them lean into their connection to things that had long been associated with country music. In her latest album, When I Get Home (which I had on r e p e a t), Solange sings of her old home in Alameda, Texas and pays homage to the Black cowboys she saw riding horses growing up. Music videos for the songs on the album had Black folks on horses, hats, boots, fringe, and all other manner of cowboy realness. Beyoncé hasn’t been too far behind. Her imagery for 2020’s “Black Parade” and Black is King both referenced the singer’s cowboy/country influences. I remember the iconic cover for her latest album, Renaissance, had the girlies by the neck when it first premiered.

As with country music, I’ve noticed a similar shift in the western literary genre.

Where before there were lone, “heroic” white men battling against the last frontier, and its many wicked and wild influences (see: Indigenous people), now there are stories with a more accurate representation of how the American West really was. There are more Black, Indigenous, and queer people showing up in stories where we should have been in the first place. Fools Crow by James Welch tells the story of white people moving west, further encroaching on Indigenous territory. Books like Outlawed by Anna North, The Good Luck Girls by Charlotte Nicole Davis, and Lucky Red by Claudia Cravens show how hostile and unwelcoming the newly colonized west could be for women and queer people. Tread of Angels by Rebecca Roanhorse and Lone Women by Victor LaValle, meanwhile, are more darkly fantastical iterations of the genre that explore isolation, race, and class.

It makes sense to me that country music and the western literary genre have had a seemingly similar trajectory. They both feel like pieces of Americana that, though their shaping has been greatly influenced by Indigenous and Black people, they’ve since become ways for white people (especially white men) to extoll their traditional values and paint themselves as hardworking and their actions as just. With this cowboy renaissance, narratives that have been taken out are being written back in.

The comments section is moderated according to our community guidelines. Please check them out so we can maintain a safe and supportive community of readers!

Leave a comment

Join All Access to add comments.