The Proof is in the Audio: How Proof Listeners Make Sure the Audiobook Matches the Print

It’s rare to survive on just one job in this economy, especially when you’re a graduate student. Luckily, I get to be a Professional Book Person in a number of different roles, like, well, Book Riot! But today I’d like to share another way to be a Professional Book Person that should be very appealing to people who have dreams of working in publishing but don’t live in New York City or don’t want to quit their day jobs: audiobook proofing.

Different companies have different shorthand for this (for example, where I got my start, they call it QC, for “quality control”), but it’s the same task regardless. You’ve heard of a proofreader, who works like a copyeditor to check for errors or general wonkiness in text, design, etc. Or maybe you’ve worked as a sensitivity reader and consulted with an editor and/or author on their manuscript, marking it up and making suggestions and corrections. It’s somewhat similar for an audiobook proof listener, actually!

First, the producer/director of the recording sends me a bunch of MP3s, as well as a PDF of the print book. It’s important that you use that, not an ARC or eARC, as those are likely to have plenty of errors as well. The producer sends you a PDF of what will be going to the printer and into the bookstores. They may also tell you that they’ve already noticed XYZ and to not worry about it or, perhaps, based on your existing relationship and expertise, they’ll ask you to pay special attention to the performer’s pronunciation of non-English words or consistency in a particular regional accent. In general, though, your task is not to give creative, developmental, or evaluative feedback, it’s to give technical notes. You are there to find inconsistencies between printed text and audio, and I mean every single thing. The text says “did not” and the performer says “didn’t?” That’s an error. They mispronounced a word? That’s an error. Skipped an entire line? Error.

Your assigning producer will probably also ask you to make note of what I’ve heard referred to as “eats, shoots, and leaves” errors — that comes from the joke about the panda who walks into a bar, kills the bartender, and walks out. Maybe the performer said every single word on the page, but their emphasis and rhythm did not match the meaning of the sentence or didn’t match the punctuation. Or maybe there’s a line that was a bit of a tongue twister, and somewhere along the lines the performer ended up mixing up some sounds. You should also make note of excessively long pauses that don’t seem to be intentional and for dramatic effect.

So how does this work?

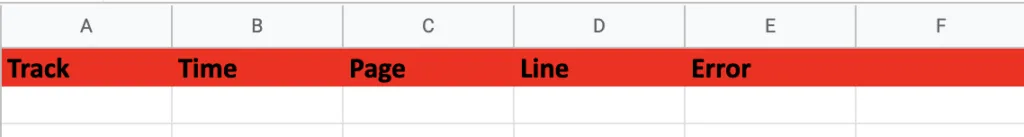

Here’s what my workflow looks like (I use a Macbook Pro and an iPhone, but PC and Android should have nearly identical applications and systems for this): I open up my phone’s Clock app and set it to the stopwatch function. This is to keep track of how much time I spend working, because I bill hourly, not by project. I open the PDF of the book and pull up the MP3s in iTunes. I turn on the Mini Player in iTunes, which will keep the play, pause, etc., on top of the screen regardless of what window or app I have on top. Finally, I open Excel and make a blank document that looks like this:

“Track” is the audio file; “time” is roughly 3 seconds before the error appears; “page” is PDF; “line” is PDF; and “error” is, well, the error.

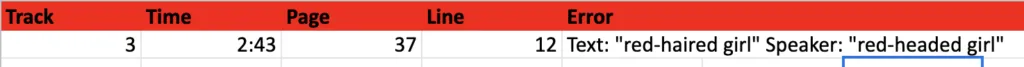

Now it’s time to work! I start the stopwatch and press play on iTunes. Now I start listening while reading every single line. It sounds easy, but it can get tedious. People tend to read text faster than they speak it, which means it’s very easy to read ahead and then realize I haven’t actually been listening at all. Then I have to rewind, because it’s very possible I missed something. Anytime I think I’ve caught a discrepancy, I rewind a few seconds and listen again. Yup, definitely an error. Pause the audio and go to the spreadsheet. Here’s what that entry would look like:

Cmd+S, just to be on the safe side, and then back to the PDF. Press Play. And so on.

One thing I’ve learned is that I have about a 45-minute limit before everything starts to swim before my eyes and I stop being able to do my job competently. At that point, I’ll stop the stopwatch, and then make a note on paper or the Notes app on my computer that says something like “Ch. 1-3: 48 minutes,” which is my way of saying that’s how long it took me to get through those chapters. The length of those chapters’ recordings might have been 34 minutes if I found a lot of errors, or 46 minutes if I found none or next to none. Then I go off and do literally anything else, ideally a screen-free activity like a workout or the dishes.

As you develop your skills and develop a relationship with the producer(s) you’re working with, they may start assigning things to you specifically because you’ve indicated that you are strong in that area — multilingual people are especially valuable here, and I find that I’m also great at keeping track of accents and pronunciation of fantasy places, so I’ve been able to note when a regional accent has changed or when the name of a country’s language and its people is the same written word but pronounced differently based on whether it’s the language or the humans and when the speaker reversed it. Not quite an “eats, shoots and leaves” issue so much as an “emPHAsis on the wrong syLLAble” thing. If you have a really good relationship with your producer, developed over time, you also become bold enough to make notes like “the text and the speaker don’t match up here, but the speaker was actually correct and the text is wrong.” My biggest point of pride is that the producer was once able to get to the editorial staff and have them stop the presses, so to speak, to fix a number of errors I found in the text before they printed it, and meanwhile I was complimenting the performer because she had naturally corrected them while speaking. To be clear, it was a fantastic book and a fantastic recording, and I actually assign it to my students, so it’s not like I thought the whole thing was garbage. I’m proud to have helped make it even better in my little way.

The best case scenario is obviously one in which there are almost no errors, and you can have a quick turnaround to your producer. It’s typical to bill about five hours for every four hours of recording, to give you an idea of how many errors you’re likely to find and how much time it takes you to pause, type, save, and get back to listening. I have had times when the recording was such a mess that it was a lot longer, and once I ended up billing almost exactly twice the length of the recording itself because there were so many problems with it (in that case, I think it was not so much performer error as technical garbling when the file saved). You send in the work, send in an invoice, and wait for your next project!

I want in!

This is not a job for everyone, but it can be really fun and rewarding if your brain is wired for it. I’ve become a better listener over time, and not only has that made me better at the job, but it’s also made me enjoy audiobooks more as a reader. I also think listening to audiobooks is a great way to become a better writer. When you listen to a piece of writing intently, you pretty quickly start to identify weird idiosyncrasies, words you rely on too often, non-parallel sentence structure, poorly tagged dialogue, and more. I highly recommend having someone read your writing aloud when you’re trying to make revisions.

If audiobook proof listening sounds like a job you’d like to try, your best bet is to contact production companies. For big publishers, that’s usually in-house, so you just have to find X Publisher’s audio division and look for contact information there. You can also look at companies that do a lot of the recording for smaller publishers, such as Brilliance Audio, an Amazon company that also handles recordings for imprints and series like Chicken Soup for the Soul. Finally, you can check freelancer websites like Fiverr.