The Year in Anti-Book Ban Laws (& What They Actually Mean): Book Censorship News, December 20, 2024

New Jersey became the latest state to pass a statewide anti-book ban bill. It happened in early December, and they joined a slate of other states who managed to pass such laws in 2024.

The wave of anti-book ban laws passed this year deserves recognition. But it also necessitates pausing to not only understand what these laws actually mean—they aren’t going to stop book censorship, for one—but also why they will not be the solution to America’s ongoing book ban problem.

In general, there are two types of anti-book ban bills being passed at the state level. The first ties a pool of money to public libraries, which might include public school libraries, to agreeing they will not ban books. That agreement may involve proving your library has a policy in place against book banning modeled after the American Library Association’s Freedom to Read statement or one that is more specific to the particular institution. If you have these things, you send proof to the designated official in the state, and you’ll receive a small grant to use for your library. In Illinois, those grants have ranged in the $800-$2000 range, which for many libraries, is a huge sum of money. This style of anti-book ban bill does not require compliance, and as reported by the Chicago Tribune, many places throughout the state have simply elected not to take the grant money.

The second type of anti-book ban bill strengthens librarian job protections. These bills codify that librarians, as part of their job, can deny book bans. They are the experts with the knowledge and resources to make developmentally—and community—appropriate collection decisions, and as such, when they defend a book’s inclusion in a library, their jobs will not be on the line. These bills are meant to encourage librarians to do the work. They’re a safety net for library workers who’ve been engaged in anti-censorship measures in their libraries. But like the other style of anti-book ban bill, these measures do not require librarians to do anything. Indeed, those already deeply engaged in quiet/silent censorship can continue unfettered. In some cases, such legislation further emboldens those who simply don’t purchase materials or inappropriately “weed” them because they can make the claim they’re doing the thing that’s best for their community (what they mean is they don’t want to do their jobs and are instead either in agreement with the complaints or are complying in advance).

These two broad categories of anti-book ban bills can overlap. Politicians who draft or sponsor these bills do so with the knowledge of what has the best possibility of being approved, thus why each piece of legislation differs (and why sometimes, you’ll see several pieces of legislation addressing all of these parts).

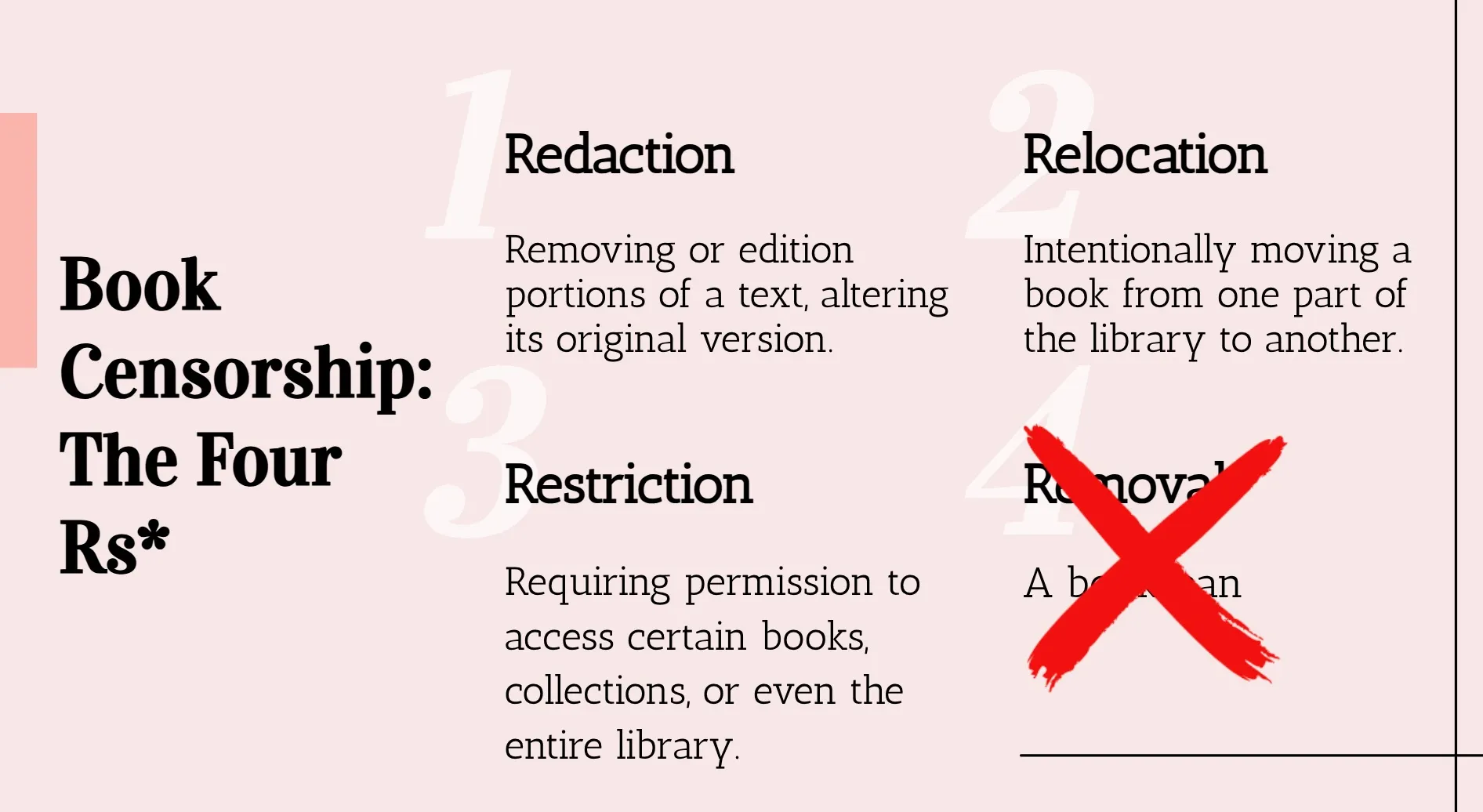

But what each of these anti-book ban bills has in common is that they address one type of book censorship: the banning part. There are, however, Four Rs of book censorship, a term and classification coined by Dr. Emily Knox:

- Restriction, or the intentional inability for books to be accessed by all who may want them. This would be putting books behind a desk so that people must ask to borrow them and may be denied if they don’t meet certain requirements.

- Redaction, the intentional editing or removal of material from a work. Cy-Fair Independent School District (TX) did this when they elected to omit sections from textbooks to be used by students that they disagreed with. Another example would be drawing underwear on a character in a book who may be nude, as was done several times in libraries in the ’70s and ’80s with Maurice Sendak’s In The Night Kitchen.

- Relocation, the intentional moving of a book from one area of the library to another. This is what Greenville County Libraries (SC) did with their youth LGBTQ+ books. It’s what was going in at East Hamilton Public Library (IN) before the board returned to actually serving its community rather than a few religious zealots.

- Removal, also known as a book ban.

Anti-book ban bills address only that last R, the actual removal of books.

That still leaves plenty of room for libraries to redact, restrict, and relocate materials, as well as engage in quiet/silent censorship. It’s not a complete end to book censorship, and because of how much latitude there is in what these bills require, so, too, is there plenty of room for continuing book bans even in states with these laws.

None of this is meant to be a downer. It’s meant to be a reminder that “good” “blue” states passing these bills still don’t have good mechanisms for addressing the reality of book censorship. Just look at Anoka County, Minnesota, schools. It’s a “good” “blue” state with an anti-book ban law on the books, and yet, the district still plans to use the slapdash, partisan creation of Moms For Liberty, BookLooks, to make decisions on whether or not to keep materials on shelves. These bills are tied to incentives or to individual protections. They are not about protecting the institutions nor the broad scope of the problem.

Moreover, none of these bills to date address the largest purveyor of book censorship, the prison system. As much as we need to fight for and on behalf of public schools and public libraries, so, too, do advocates for the freedom to read and freedom to think need to be advocating for those experiencing incarceration. Access to books and libraries reduces recidivism and has an incredible impact on those on the inside (see this, this, and this). Prison censorship is directly related to America’s legacy of slavery.

There is something especially important in these bills, though, and it’s this: politicians working to get anti-book ban bills passed are signaling to constituents that they are listening to library workers. They are championing the institutions being attacked. Even if their attempts are only moderately successful in addressing the issues, they’re majorly symbolic. These legislators are the ones that not only library workers should continue to get into the ears (and inboxes) of, but so, too, should every citizen concerned about what’s happening in libraries both in their state and beyond. As you’re planning your 2025 pro-library, anti-book censorship advocacy, learn who was behind these bills in your state and reach out to them. Tell them what else they can be doing and provide them with the data and anecdotes to help bolster why they should act now.

So, as we round out 2024 in book censorship news, here’s a roundup of the eight states that have successfully passed anti-book ban laws. I’ve included a short description of what is in each bill, but you can and should visit the bills as passed to learn more.

California

Addresses Public Schools & Public Libraries

California passed its first anti-book ban bill as it relates to public schools in 2023. This bill disallows school boards to ban books that they deem inappropriate and bans related to partisan or doctrinal belief. It should be noted that at the same time this anti-book banning measure came up, there was a bill floating in the state legislature that would allow parents to sue school boards for not banning books fast enough.

The state then passed one for public libraries in 2024 through Assembly Bill 1825. The public bill ties funding to having intellectual freedom policies, much like Illinois, and it also strengthens protections of librarians who defend their collections. The bill will go into effect January 1, 2026. You can see how excited some of the local politicians are about it, too; Fresno County’s supervisor will have his little parent book banning committee invalidated.

Colorado

Addresses Public Libraries

Passed in early June 2024, Colorado has implemented new laws requiring every public library to have a collection policy and, if they allow for books to be challenged, requiring policies governing the process. One thing this particular bill does that is noteworthy is it requires keeping track of the outcomes of every official book challenge in public libraries. It also makes the names of those seeking to remove books public. Both of these add a crucial layer of transparency to the process. The bill does not, however, codify that books cannot be removed for discriminatory reasons (though that was in the original draft).

Retaliation against library workers for defending books is included in this bill.

Illinois

Addresses Public Schools & Public Libraries

The Prairie State made history as the first to pass an anti-book ban law. The law ties funding to intellectual freedom policies in public and public school libraries. If a library wants access to a pot of state money for their institution, they need to have in their collection policies the American Library Association’s Library Bill of Rights and/or a comparable statement upholding the rights of everyone to access materials in the collection. Books and other items in the library cannot be removed for partisan or discriminatory reasons.

Maryland

Addresses Public Libraries and Public Schools

Maryland’s Freedom to Read Act protects access to books and other library items by stating they cannot be removed or prohibited from collections because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval. Collections seek to serve the research and recreational needs of all, and materials cannot be excluded based on the origin, background, or views of their creator. Both school and public libraries would need to have collection development policies in place, and if a book were to be challenged, the title would remain on shelves and available for use through the reconsideration process.

You may note this bill has not stopped book banning in the state. Seven books were banned from Carroll County Public Schools after the bill’s passage and Montgomery County Schools bowed to pressure from the local bigotry brigade and pulled two LGBTQ+ inclusive books about family from curriculum.

Minnesota

Addresses Public Libraries, Public Schools, and Public Institutions of Higher Education

Minnesota’s governor signed off on Senate File 3567 as part of a robust education bill. All of these institutions are now required to have collection policies, as well as guidelines for the selection and reconsideration of material. This is similar to that passed in Colorado, though Minnesota’s bill makes it clear books cannot be removed on the basis of viewpoint or opinion alone.

New Jersey

Addresses Public Schools and Libraries

The just-passed Freedom to Read bill in New Jersey offers protections for librarians who are defending the right to have books accessible in their collections, and it also requires school and public libraries to have policies about where and how materials are acquired, evaluated, and go through the challenge process (if complaints are filed). Books cannot be banned based on politics or doctrine, and only people who have a vested interest in a school community can lodge challenges. This will deter, for example, members of Moms For Liberty or other groups from challenging books if they don’t actually live in the community of the school to which they’re complaining.

Something of note: as mentioned above, this bill is not the original bill as introduced. Several of the protections initially proposed were moved, including one that would ensure librarians are not discriminated against in future hiring decisions based on their anti-book ban experiences in previous institutions.

The bill goes into effect next year.

Vermont

Addresses Public Libraries

One of the more robust bills passed in 2024 is Vermont’s Protecting Libraries and the Freedom to Read Bill. Among the provisions are requiring libraries to have policies that align with the First Amendment and anti-discrimination laws. Legal protections for libraries and library workers throughout the state have been strengthened as well as more robust opportunities for education around libraries and their role in community and civic life would be created for library workers and trustees.

What makes Vermont’s legislation stand out, aside from its clear commitment to upholding and championing libraries, is that its emergence came following a report put together by library workers to give the legislature a real picture of the current state of the state’s institutions. You can read the full working group report here.

Washington

Addresses Public Schools

HB 2331 is similar to the California bill in that it bars school boards from banning books, curriculum, textbooks, and other materials from use for discriminatory reasons. By the 2025-2026 school year, boards need to have in place policies related to supplemental materials (i.e., library and classroom materials) and how those are reviewed and evaluated were they to be challenged.

Note: This edition of Literary Activism inadvertently left off another state with an anti-book ban law and that’s Connecticut’s Public Act 23-101. That bill opens up a pool of funds for public libraries who meet a short list of criteria, including that they will not ban books.

*

For the 2025 legislative session, there are already three states with anti-book ban bills on the docket. These include Missouri (in the Senate addressing public schools and libraries and in the House, any library receiving state funds) Arkansas (addressing school and public libraries), and Michigan (addressing public libraries and district libraries). Anticipate also seeing bills be revisited in states that did not pass anti-book ban bills in 2024 in the coming session, including Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, and more. There’s also an interesting research study being conducted in regard to Senate Bill 1531 from Massachusetts that explores the problem of banned books in state prisons.

The US Senate Resolution 857 isn’t dead yet, either, though with the incoming administration, chances of seeing this one move any further are marginal.

Book Censorship News: December 20, 2024

- Saydel Community School District (IA) has pulled 21 books for review under the state’s book ban law. The list is the usual suspects, including The Handmaid’s Tale, The Bluesy Eye, Me & Earl & The Dying Girl, Sold, Breaking Dawn, and more.

- A new bill being proposed in Pennsylvania would criminalize librarians and require that all students be opted-in to books. This form is absolutely absurd and passes absolute lies off as truth to further whip up a frenzy over “pornographic” books in libraries that DO NOT EXIST.

- One legislator in Missouri proposed a bill for the coming session that would require all kinds of nonsense disclosures about potential porn in library materials. This is a new angle in this year’s bills: if you “inform” the parent/guardian about “potential porn” in the library, you whip up a good frenzy for your cause when there is no such thing as porn in the library, period.

- A new report highlights the inconsistencies of prison book bans in New York.

- Oh, you don’t say that the surprise book challenges at a Platteville, Wisconsin, middle school happened right after the new Moms for Liberty chapter in the county met? Color me shocked.

- Speaking of, Moms For Liberty is happy about new book

banchallenge policies in Volusia County Schools (FL). - And speaking of both Volusia AND Moms For Liberty: “During a session at the Moms for Liberty 2024 Joyful Warriors Summit in Washington, D.C., Jessie Thompson—the new Volusia County School Board chair—made a disparaging remark about Deltona High School students, admitted to feeding false data to the board to get agenda items passed, and spoke at length about her poor relationships with fellow board members.” Remember how Volusia wanted to “invest in” BookLooks as their review source?

- Read Freely Alabama talks about the state’s banning of books related to sexual education in libraries and schools.

- People showed up to discuss the impact of potential LGBTQ+ and trans-specific book bans at Addison Central School District (VT).

- It’s still not clear yet what Bellaire Public Library (MI) will do following the challenge of the Heartstopper books. But the info in this piece that made it worth sharing is that the library ALREADY MOVED ITS YA SECTION to avoid this kind of fake outrage.

- Lancaster Public Library (PA) is trying to figure out how to find funding since many of their usual sources are choosing not to in the coming year. Why? Bigotry.

- ONE parent complained about Lily & Duncan by Donna Gephardt in Johnson County Schools (KS), so the book is being removed. This is despite a review committee voting overwhelmingly to keep it. Remember: one complaint, and one board wanting to keep her and her bigot friends happy.

- Here’s what’s happening with mass book bans in Tennessee.

- “Several organizations critical of Florida’s restrictions on education materials are warning school officials against removing books that contain health information—even if that information has been removed from the health curriculum for middle school students.” Did you know some of the curriculum Florida has banned includes teaching consent? Imagine how they’ll apply their new standards to library books.

- Right wing book banners have huge power on the Conroe Independent School District (TX) board, and they plan on wielding it. Remember “mama bears” are just Moms For Liberty under a different name.

- In news that isn’t news but is worthy of repeating: when school boards are being overwhelmed with book ban bs, they can’t do their actual jobs. Also, they’re harassed for doing what’s right.

- The Lehighton Area School District Board of Directors (PA) is readying a form that allows parents to opt-in to letting their kids access 33 books in the district that the board things are not appropriate. The books are the usual suspects from BookLooks and other book-banning “review” websites.

- How Christian nationalists are shaping Texas’s public education. Recall: this is all part of the long game to get vouchers shoved through in Texas, which has been a holdout among other red states.

- “Trimming the State Library’s budget would eliminate the vast majority of funding for the organization, which is an arm of the state Department of Education. The library currently has 21 employees; the budget cut would lay off a dozen of them, according to the governor’s proposal.” This is in South Dakota and one way to begin killing public goods in the state.

- Are you in Warren County, Virginia, where the county is trying to kill Samuels Public Library after a years’ long effort from a local church group? Apply to be on their new library board.

- Portage Public Schools (MI) will not be banning The Breadwinner, which some complainers said had inappropriate content.

- A federal judge is telling Escambia County Schools (FL) to stop wasting so much taxpayer money and settle the lawsuit against them for banning books.

- It looks like some “conservative activists” are trying to get on the Denton, Texas, public library board. This week, they approved her appointment.

- Charleston County School District (SC) is now no longer allowing anyone in 12th grade or younger to access ebooks or audiobooks via the digital Sora app that is rated above juvenile. You read that right: high schoolers can’t use Sora to get YA books or adult books (which include classics and thousands of perfectly appropriate books for them). We’ll see this happening more, as this is an issue arising between a public school and a public library partnership.

- The nominee for New Hampshire’s State Librarian has had that nomination revoked. Why? Because she opposes book bans.

- Watch for the next list of dozens of books to be removed from Blount County Schools (TN) soon. This is in part because of the state’s new law and part because of a local soon-to-be Moms For Liberty chapter who believes they are “making progress.”

- “The Derby school district near Wichita [KS] has rejected a proposed social studies curriculum for high school students over concerns that some materials are biased against Republican President-elect Donald Trump.” Biggest eye roll ever, especially the part about how the publisher’s website talks about anti-racism being an issue.

- Prattville Public Library (AL) is far from out of the woods when it comes to nonstop attacks. A controversial board member is back on the board.

- A new bill pre-filed in South Carolina would make it law that libraries have to follow the

whimspreoccupationsrules related to “inappropriate content” or face losing their funding. Think of this as the opposite of, say, Illinois’s anti-book ban law.