Anatomy of a Scene: Great Expectations, Pip and Joe’s Reunion

What already feels like eons ago, at the beginning of 2016, the choice for my first Anatomy of a Scene of the year seemed obvious. I could piggyback off of December’s post and look at another one of Charles Dickens’ most famous and well-known works. And besides, what could be more punnily fitting for the beginning of the new year – with all its hope and resolution – than Great Expectations?

I am probably not alone in saying that January has been a hell of a month. It’s possible our own expectations are not quite as bright as they had been at the beginning of the month (I, for example, greatly expected I would have this post ready in time to be published in January. As you might have guessed, I disappointed my own expectations in that particular regard). But really, that only makes Dickens’ tale of reinvention, betrayal and frustrated longing all the more appropriate.

I am on record as a huge lover of Miss Havisham, but when I think about adaptations of Great Expectations, the scene that always sticks with me is the first reunion between Pip and Joe in Chapter 27.

In this scene, Pip has been installed in London with his fortune and has begun to live the life of a young gentleman when he receives a visit from his guardian, rural blacksmith Joe Gargery. Pip recounts his feelings about Joe’s visit as “considerable disturbance; some mortification, and a keen sense of incongruity.” “If I could have kept him away by paying money, I certainly would have,” he reflects unflinchingly. Pip is desperate to establish himself as a gentleman to win Estella and the respect of peers; for him Joe represents an inconvenient and uncomfortable reflection of the past from which he yearns to distance himself.

Joe’s manner throughout this scene simultaneously heart wrenching and cringe-inducing. He arrives overdressed and he openly gapes at Pip’s lavish quarters. He immediately recognizes that that he doesn’t belong, and some of his more bizarre behaviours come across clearly as an attempt to make as little mark as possible on his nephew’s new life. He wipes his feet on the doormat for what seems a small eternity. He cannot bring himself to express a preference for either tea or coffee. He is extremely hesitant to relinquish his hat, and when he does, he insists on perching it precariously on the edge of the fireplace.

All of this exacerbates Pip’s feelings; he becomes angry and impatient and Joe is certainly not oblivious. Before he leaves, Joe tells Pip that it is time for them to truly part. He claims all fault for the discomfort of this meeting between them and admits that he and Pip “are not two figures to be seen together in London.” Assuaging any worries about future unexpected visits, Joe tells Pip that if Pip wants to see him again Pip can visit the forge. Going forward their relationship will be entirely on Pip’s terms. Essentially, Joe releases him.

This small scene, while lacking the Gothic drama of Pip’s interactions with Estella, Magwitch, or Miss Havisham, is crucial to Pip’s character arc, and it really gets to the heart of the tensions that animate Great Expectations: between love and shame, goodness and greatness, and quality and class. It’s also a great example of Dickens’ refusal to let his readers off the hook: a scene that simultaneously mirrors and repels.

It would be easy to criticize Pip’s callow lack of gratitude and to want to reach through the pages and shake him (guilty as charged). But how many of us haven’t had a similar moment in our own lives, when a well-meaning parent or friend embarrassed us with their inability to fit in, know how to act, or just behave? How many of us haven’t felt even a flicker of that projected self-loathing? How many of us haven’t treating someone who deserved better badly because they forced us to reckon with our most vulnerable, inappropriate selves?

**********

There are too many adaptations of Great Expectations alone to cover here, so I tried to cast a wide net of readily-available choices and ultimately decided on the 1946 and 1998 film adaptations and the televised miniseries from 2011. Together they represent: two straight adaptations and one modernization, two films and one miniseries, and a span of sixty-five years.

First up is David Lean’s gorgeous 1946 film adaptation, still widely considered a classic and an inspiration to everyone from Joel Schumacher to Donald Sutherland. Lean and co.’s script (there are five credited screenwriters) is a faithful if significantly abridged adaptation Dickens’ novel.

Of the three adaptations I’ve selected, this one maintains the most textually-faithful version of the “reunion” scene between Pip and Joe, and Joe as written and as performed by a wild-eyed Bernard Miles is the most strictly faithful adaptation of the character. Lean includes and even augments Joe’s awkward preoccupation with his hat, adding a clumsy off-camera bit of business resulting in Joe knocking over the table and dunking his hat in a pot of tea. Joe’s fumbling begets this rather disdainful look between Pip and Herbert Pocket (a young Alec Guinness).

Lean also uses set and costume to visually communicate that Joe is out of his element. Pip’s apartment and his person are decorated in soft, curving lines and lush draped fabrics. By contrast, Joe arrives stuffed into a stark, too-small jacket. His dark, owlish eyebrows and the sharp, exaggerated lapels of collar give the impression of Joe as a series of awkward angles, setting him visually at odds with Pip and his baroque chambers.

Lean also uses set and costume to visually communicate that Joe is out of his element. Pip’s apartment and his person are decorated in soft, curving lines and lush draped fabrics. By contrast, Joe arrives stuffed into a stark, too-small jacket. His dark, owlish eyebrows and the sharp, exaggerated lapels of collar give the impression of Joe as a series of awkward angles, setting him visually at odds with Pip and his baroque chambers.

Lean’s real genius shines through in two poignant, incredibly well-composed shots that bracket this scene.The first is of Pip looking out his window at Joe as he arrives. Pip is literally looking down his nose at Joe and the windowpane creates a barrier between them. This shot set the stage for what will follow; before anything is said or done the film communicates Pip’s distance from Joe.

Lean’s real genius shines through in two poignant, incredibly well-composed shots that bracket this scene.The first is of Pip looking out his window at Joe as he arrives. Pip is literally looking down his nose at Joe and the windowpane creates a barrier between them. This shot set the stage for what will follow; before anything is said or done the film communicates Pip’s distance from Joe.

The final shot of this scene, after Joe has delivered his message to Pip and taken his leave, is of Pip catching his own eye in the mirror. Pip takes in his face, his clothes and his surrounding, and ultimately he can’t meet his own eyes. Clearly he doesn’t like what he sees. It’s a moment of self-reflection and of revelation, the seed of the hard lessons he’ll learn in the weeks to follow.

The final shot of this scene, after Joe has delivered his message to Pip and taken his leave, is of Pip catching his own eye in the mirror. Pip takes in his face, his clothes and his surrounding, and ultimately he can’t meet his own eyes. Clearly he doesn’t like what he sees. It’s a moment of self-reflection and of revelation, the seed of the hard lessons he’ll learn in the weeks to follow.

Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 update of Great Expectations recasts Pip (here called Finn and played by Ethan Hawke) as an aspiring artist from working-class Florida whose mysterious benefactor sends him to live in Manhattan and sponsors and publicizes his first gallery show.

In discussions of the glut of ’90s literary updates Great Expectations is often unfairly overlooked, but it is both a gorgeous film in its own right and an excellent adaptation. Screenwriter Mitch Glazer modernizes and streamlines Dickens’ novel and Cuarón, a master of his craft, packs dense visual allusions and imbues meaning into every lush frame. Of all the filmmakers discussed here, Cuarón and Glazer are the team that most obviously share my attachment to this scene between Pip/Finn and Joe they weave this moment into the very moment the entire film the scene has been building toward – Finn’s gallery opening.

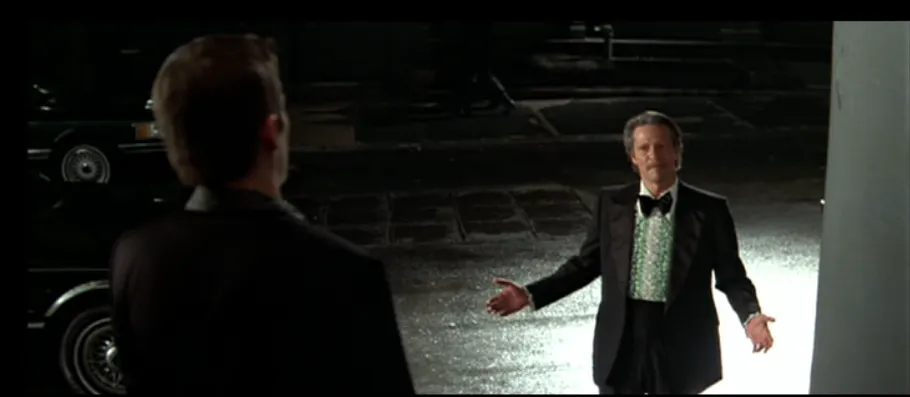

Cuarón’s version takes this moment from an uncomfortable but private encounter to a public scene. Finn’s opening is already in full swing when Joe (Chris Cooper) shows up, unannounced and uninvited. Hawke’s Finn is obviously panicked; he stutters, winces, and ineffectually attempts to hustle Joe out of the gallery before he is seen. Cooper plays Joe as warm and well-meaning but ungainly. His voice is pitched too loud, his accent is too broad, and his language too coarse (Finn cringes when Joe jovially calls the Jagger character, Ragno, a ‘sonofabitch’).

Joe stands out visually, too. In a sea of slouchy cashmere sweaters, chic pencil skirts, and wool blazers slung casually over jeans, Joe’s shoddy-looking, too-formal ‘70s-era tuxedo is a sartorial anomaly. One of Cuarón’s strokes of visual genius is the beautiful, strategic use of green – a colour alternately and sometimes simultaneously connoting wealth, envy, and nature – in all the costumes and sets.

Cuarón uses the variety of his colour palette to great advantage in this scene: the gallery-goers run the gambit of rich hunter green to understated khaki to brilliant lime. Again Joe is visually coded as an outsider. Joe’s touch of green in the spearmint ruffles of his tuxedo shirt, is suggestive of nothing more the chewing gum: cheap, tacky and disposable.

Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 update of Great Expectations recasts Pip (here called Finn and played by Ethan Hawke) as an aspiring artist from working-class Florida whose mysterious benefactor sends him to live in Manhattan and sponsors and publicizes his first gallery show.

In discussions of the glut of ’90s literary updates Great Expectations is often unfairly overlooked, but it is both a gorgeous film in its own right and an excellent adaptation. Screenwriter Mitch Glazer modernizes and streamlines Dickens’ novel and Cuarón, a master of his craft, packs dense visual allusions and imbues meaning into every lush frame. Of all the filmmakers discussed here, Cuarón and Glazer are the team that most obviously share my attachment to this scene between Pip/Finn and Joe they weave this moment into the very moment the entire film the scene has been building toward – Finn’s gallery opening.

Cuarón’s version takes this moment from an uncomfortable but private encounter to a public scene. Finn’s opening is already in full swing when Joe (Chris Cooper) shows up, unannounced and uninvited. Hawke’s Finn is obviously panicked; he stutters, winces, and ineffectually attempts to hustle Joe out of the gallery before he is seen. Cooper plays Joe as warm and well-meaning but ungainly. His voice is pitched too loud, his accent is too broad, and his language too coarse (Finn cringes when Joe jovially calls the Jagger character, Ragno, a ‘sonofabitch’).

Joe stands out visually, too. In a sea of slouchy cashmere sweaters, chic pencil skirts, and wool blazers slung casually over jeans, Joe’s shoddy-looking, too-formal ‘70s-era tuxedo is a sartorial anomaly. One of Cuarón’s strokes of visual genius is the beautiful, strategic use of green – a colour alternately and sometimes simultaneously connoting wealth, envy, and nature – in all the costumes and sets.

Cuarón uses the variety of his colour palette to great advantage in this scene: the gallery-goers run the gambit of rich hunter green to understated khaki to brilliant lime. Again Joe is visually coded as an outsider. Joe’s touch of green in the spearmint ruffles of his tuxedo shirt, is suggestive of nothing more the chewing gum: cheap, tacky and disposable.

Seen through Finn’s eyes, Joe is big, colourful, garish, too much. For half the scene, Cuarón frames Joe in front of a larger-than-life black-and-white portrait of himself. From Finn and the audience’s viewpoint, Joe seems to pop out of the frame, simultaneously diminished and (for Finn, uncomfortably) vital.

Seen through Finn’s eyes, Joe is big, colourful, garish, too much. For half the scene, Cuarón frames Joe in front of a larger-than-life black-and-white portrait of himself. From Finn and the audience’s viewpoint, Joe seems to pop out of the frame, simultaneously diminished and (for Finn, uncomfortably) vital.

The culmination of Finn’s embarrassment is when Joe, gesturing wildly, knocks over a server’s tray of champagne — and then gets down on his hands and knees to help her clean up. The camera reinforces Finn’s view of Joe, filming the scene from above to emphasize Joe’s lowly, crouching position. Finn is mortified. He knows by now it’s the rich and glamorous who make messes; cleaning them up is for everyone else.

The culmination of Finn’s embarrassment is when Joe, gesturing wildly, knocks over a server’s tray of champagne — and then gets down on his hands and knees to help her clean up. The camera reinforces Finn’s view of Joe, filming the scene from above to emphasize Joe’s lowly, crouching position. Finn is mortified. He knows by now it’s the rich and glamorous who make messes; cleaning them up is for everyone else.

Flustered, Finn screams at Joe to “just LEAVE IT!” It’s in this moment that it dawns on Joe with heartbreaking clarity that is presence isn’t welcome. Chris Cooper is absolutely tremendous here; an actor to break your damn heart. You can literally see the realization that he is an embarrassment to Finn cross his face.

Flustered, Finn screams at Joe to “just LEAVE IT!” It’s in this moment that it dawns on Joe with heartbreaking clarity that is presence isn’t welcome. Chris Cooper is absolutely tremendous here; an actor to break your damn heart. You can literally see the realization that he is an embarrassment to Finn cross his face.

Joe quickly leaves and, after a beat, Finn eventually chases him out, but he stops before ever really leaving the gallery. Joe stands outside on the street while Finn stands above him on the staircase. The effect is a camera that elevates Finn and looks down on Joe: Joe is on the outside, looking in and Finn is perched liminally on the doorstep, on his way up.

Joe quickly leaves and, after a beat, Finn eventually chases him out, but he stops before ever really leaving the gallery. Joe stands outside on the street while Finn stands above him on the staircase. The effect is a camera that elevates Finn and looks down on Joe: Joe is on the outside, looking in and Finn is perched liminally on the doorstep, on his way up.

Directed by Brian Kirk and written by Sarah Phelps, the BBC’s 2011 Great Expectations miniseries is, visually and thematically, a dark and, yes, even gritty take on Dickens’ novel, including a visit to a brothel and a rather graphic self-immolation. Phelps’ screenplay hews to the plot and characters of the novel quite closely, but the dialogue is often significantly different; Joe is the character most altered in Phelps’ script. Far from the awkward, occasionally buffoonish, but dignified Joe of the novel and Lean’s film, this Joe is confident, proud, forthcoming with his feelings and opinions, and, in this particular scene, angry.

Like Cuarón, Kirk stages the beginning of this scene in public. Joe surprises Pip at his gentlemen’s club where he is drinking with Herbert Pocket. Shaun Dooley’s physicality immediately marks him as different from the rest of the men in the club. His big, frizzy hair and ruddy cheeks contrast with the dark, languorous curls and pallid skin of Pip and Herbert.

Directed by Brian Kirk and written by Sarah Phelps, the BBC’s 2011 Great Expectations miniseries is, visually and thematically, a dark and, yes, even gritty take on Dickens’ novel, including a visit to a brothel and a rather graphic self-immolation. Phelps’ screenplay hews to the plot and characters of the novel quite closely, but the dialogue is often significantly different; Joe is the character most altered in Phelps’ script. Far from the awkward, occasionally buffoonish, but dignified Joe of the novel and Lean’s film, this Joe is confident, proud, forthcoming with his feelings and opinions, and, in this particular scene, angry.

Like Cuarón, Kirk stages the beginning of this scene in public. Joe surprises Pip at his gentlemen’s club where he is drinking with Herbert Pocket. Shaun Dooley’s physicality immediately marks him as different from the rest of the men in the club. His big, frizzy hair and ruddy cheeks contrast with the dark, languorous curls and pallid skin of Pip and Herbert.

Joe strides into the club, broad shoulders squared, and barks at the porter that he has “no cause to lay hands on me.” Pip, obviously mortified, cannot look Joe in the eye or even speak to him. He all but flees, returning to his flat with Joe following on his heels.

Once behind closed doors the viewer gets a better sense of why, in this version, Joe has come: both to check on Pip and to chastise him. Joe scolds Pip for not writing, even to let them know that he was well; he reminds Pip that his bedridden sister “lives for” news from him. Pip appears not so much unmoved as unwilling to be moved. Throughout this scene Kirk shoots Booth in a series of tight close-ups that emphasize his inability to meet Joe’s eyes.

Joe strides into the club, broad shoulders squared, and barks at the porter that he has “no cause to lay hands on me.” Pip, obviously mortified, cannot look Joe in the eye or even speak to him. He all but flees, returning to his flat with Joe following on his heels.

Once behind closed doors the viewer gets a better sense of why, in this version, Joe has come: both to check on Pip and to chastise him. Joe scolds Pip for not writing, even to let them know that he was well; he reminds Pip that his bedridden sister “lives for” news from him. Pip appears not so much unmoved as unwilling to be moved. Throughout this scene Kirk shoots Booth in a series of tight close-ups that emphasize his inability to meet Joe’s eyes.

The two actors are even physically set at odds. When Joe follows Pip from the club, he is all but chasing him. And when they arrive at Pip’s chambers, they stand facing each other on opposite sides of the frame, looking less like companions than combatants.

The two actors are even physically set at odds. When Joe follows Pip from the club, he is all but chasing him. And when they arrive at Pip’s chambers, they stand facing each other on opposite sides of the frame, looking less like companions than combatants.

Up until this point Joe seems to believe Pip has been careless: that the lack of communication of him has been self-involved but accidental. It is only when they discuss who would even read his letters that Joe realizes the truth. When Joe suggests the petty, officious Pumblechook as the obvious candidate, Pip sneers that Pumblechook only wants to brag that he gave Pip his start in life. Joe shrugs, “He’s an idiot, let him brag. It doesn’t hurt you.” Pip snaps back, “Oh doesn’t it?”

Joe suddenly realizes that Pip is ashamed (“ashamed of me, ashamed of home”) and that that shame is hurting him, very much. It’s at this moment that the Joe of Phelps’ script most strongly evokes the Joe of Dickens’ novel – compassionate, generous, and loving. Because whether or not Pip should feel ashamed is immaterial; the fact of his pain is enough.

Joe’s entire demeanour changes. He softens toward Pip and physically broaches the gap between them. Flustered, Pip responds with the frustrated, deeply-felt cry of every teenager at some point or another: “you don’t understand!” In response, Joe gently gathers Pip’s head in his hands, the kind of embrace reserved for children or the vulnerable and distraught. Instead of the blessing of Dickens’ text, here Joe kisses Pip on the forehand and whispers “I understand.”

Up until this point Joe seems to believe Pip has been careless: that the lack of communication of him has been self-involved but accidental. It is only when they discuss who would even read his letters that Joe realizes the truth. When Joe suggests the petty, officious Pumblechook as the obvious candidate, Pip sneers that Pumblechook only wants to brag that he gave Pip his start in life. Joe shrugs, “He’s an idiot, let him brag. It doesn’t hurt you.” Pip snaps back, “Oh doesn’t it?”

Joe suddenly realizes that Pip is ashamed (“ashamed of me, ashamed of home”) and that that shame is hurting him, very much. It’s at this moment that the Joe of Phelps’ script most strongly evokes the Joe of Dickens’ novel – compassionate, generous, and loving. Because whether or not Pip should feel ashamed is immaterial; the fact of his pain is enough.

Joe’s entire demeanour changes. He softens toward Pip and physically broaches the gap between them. Flustered, Pip responds with the frustrated, deeply-felt cry of every teenager at some point or another: “you don’t understand!” In response, Joe gently gathers Pip’s head in his hands, the kind of embrace reserved for children or the vulnerable and distraught. Instead of the blessing of Dickens’ text, here Joe kisses Pip on the forehand and whispers “I understand.”

**********

The final thing I want to examine in these three scenes is the last thing Joe says to Pip before he leaves. Each film gives Joe a different parting line suited to the audience but the sentiment – reassurance, benevolence and love – remains the same.

In the David Lean adaptation, aimed at an audience who had likely lived through Depression and at least one war, Joe’s last line in this scene is taken straight from Dickens’ text: “God bless you.” Lean’s audience would recognize this as an invocation, a benediction, and a call for protection, not just for Pip’s body but his immortal soul.

In Alfonso Cuarón’s Gen-X modernization, when the line is being delivered to the Hollywood poster boy of the slacker generation, the line becomes “I’m proud of you, Finn. I always have been.” For the 2011 adaptation Sarah Phelps was insistent on casting Pip young to show “somebody finding their feet as an adult, dealing with growing up.” The result is a Great Expectations starring (and presumably geared toward) that much-discussed, oft-derided but rarely truly understood commodity: a millennial. And in this case Joe’s last line becomes an emphatic, comforting “I understand.”

This, to me, is what makes adaptations are so fascinating. Stories like Great Expectations persist because they manage to be both robust and infinitely malleable. They can be shaped and tweaked into something fresh and urgent all while remaining undeniably, irrefutably themselves.

**********

The final thing I want to examine in these three scenes is the last thing Joe says to Pip before he leaves. Each film gives Joe a different parting line suited to the audience but the sentiment – reassurance, benevolence and love – remains the same.

In the David Lean adaptation, aimed at an audience who had likely lived through Depression and at least one war, Joe’s last line in this scene is taken straight from Dickens’ text: “God bless you.” Lean’s audience would recognize this as an invocation, a benediction, and a call for protection, not just for Pip’s body but his immortal soul.

In Alfonso Cuarón’s Gen-X modernization, when the line is being delivered to the Hollywood poster boy of the slacker generation, the line becomes “I’m proud of you, Finn. I always have been.” For the 2011 adaptation Sarah Phelps was insistent on casting Pip young to show “somebody finding their feet as an adult, dealing with growing up.” The result is a Great Expectations starring (and presumably geared toward) that much-discussed, oft-derided but rarely truly understood commodity: a millennial. And in this case Joe’s last line becomes an emphatic, comforting “I understand.”

This, to me, is what makes adaptations are so fascinating. Stories like Great Expectations persist because they manage to be both robust and infinitely malleable. They can be shaped and tweaked into something fresh and urgent all while remaining undeniably, irrefutably themselves.

Lean also uses set and costume to visually communicate that Joe is out of his element. Pip’s apartment and his person are decorated in soft, curving lines and lush draped fabrics. By contrast, Joe arrives stuffed into a stark, too-small jacket. His dark, owlish eyebrows and the sharp, exaggerated lapels of collar give the impression of Joe as a series of awkward angles, setting him visually at odds with Pip and his baroque chambers.

Lean also uses set and costume to visually communicate that Joe is out of his element. Pip’s apartment and his person are decorated in soft, curving lines and lush draped fabrics. By contrast, Joe arrives stuffed into a stark, too-small jacket. His dark, owlish eyebrows and the sharp, exaggerated lapels of collar give the impression of Joe as a series of awkward angles, setting him visually at odds with Pip and his baroque chambers.

Lean’s real genius shines through in two poignant, incredibly well-composed shots that bracket this scene.The first is of Pip looking out his window at Joe as he arrives. Pip is literally looking down his nose at Joe and the windowpane creates a barrier between them. This shot set the stage for what will follow; before anything is said or done the film communicates Pip’s distance from Joe.

Lean’s real genius shines through in two poignant, incredibly well-composed shots that bracket this scene.The first is of Pip looking out his window at Joe as he arrives. Pip is literally looking down his nose at Joe and the windowpane creates a barrier between them. This shot set the stage for what will follow; before anything is said or done the film communicates Pip’s distance from Joe.

The final shot of this scene, after Joe has delivered his message to Pip and taken his leave, is of Pip catching his own eye in the mirror. Pip takes in his face, his clothes and his surrounding, and ultimately he can’t meet his own eyes. Clearly he doesn’t like what he sees. It’s a moment of self-reflection and of revelation, the seed of the hard lessons he’ll learn in the weeks to follow.

The final shot of this scene, after Joe has delivered his message to Pip and taken his leave, is of Pip catching his own eye in the mirror. Pip takes in his face, his clothes and his surrounding, and ultimately he can’t meet his own eyes. Clearly he doesn’t like what he sees. It’s a moment of self-reflection and of revelation, the seed of the hard lessons he’ll learn in the weeks to follow.

Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 update of Great Expectations recasts Pip (here called Finn and played by Ethan Hawke) as an aspiring artist from working-class Florida whose mysterious benefactor sends him to live in Manhattan and sponsors and publicizes his first gallery show.

In discussions of the glut of ’90s literary updates Great Expectations is often unfairly overlooked, but it is both a gorgeous film in its own right and an excellent adaptation. Screenwriter Mitch Glazer modernizes and streamlines Dickens’ novel and Cuarón, a master of his craft, packs dense visual allusions and imbues meaning into every lush frame. Of all the filmmakers discussed here, Cuarón and Glazer are the team that most obviously share my attachment to this scene between Pip/Finn and Joe they weave this moment into the very moment the entire film the scene has been building toward – Finn’s gallery opening.

Cuarón’s version takes this moment from an uncomfortable but private encounter to a public scene. Finn’s opening is already in full swing when Joe (Chris Cooper) shows up, unannounced and uninvited. Hawke’s Finn is obviously panicked; he stutters, winces, and ineffectually attempts to hustle Joe out of the gallery before he is seen. Cooper plays Joe as warm and well-meaning but ungainly. His voice is pitched too loud, his accent is too broad, and his language too coarse (Finn cringes when Joe jovially calls the Jagger character, Ragno, a ‘sonofabitch’).

Joe stands out visually, too. In a sea of slouchy cashmere sweaters, chic pencil skirts, and wool blazers slung casually over jeans, Joe’s shoddy-looking, too-formal ‘70s-era tuxedo is a sartorial anomaly. One of Cuarón’s strokes of visual genius is the beautiful, strategic use of green – a colour alternately and sometimes simultaneously connoting wealth, envy, and nature – in all the costumes and sets.

Cuarón uses the variety of his colour palette to great advantage in this scene: the gallery-goers run the gambit of rich hunter green to understated khaki to brilliant lime. Again Joe is visually coded as an outsider. Joe’s touch of green in the spearmint ruffles of his tuxedo shirt, is suggestive of nothing more the chewing gum: cheap, tacky and disposable.

Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 update of Great Expectations recasts Pip (here called Finn and played by Ethan Hawke) as an aspiring artist from working-class Florida whose mysterious benefactor sends him to live in Manhattan and sponsors and publicizes his first gallery show.

In discussions of the glut of ’90s literary updates Great Expectations is often unfairly overlooked, but it is both a gorgeous film in its own right and an excellent adaptation. Screenwriter Mitch Glazer modernizes and streamlines Dickens’ novel and Cuarón, a master of his craft, packs dense visual allusions and imbues meaning into every lush frame. Of all the filmmakers discussed here, Cuarón and Glazer are the team that most obviously share my attachment to this scene between Pip/Finn and Joe they weave this moment into the very moment the entire film the scene has been building toward – Finn’s gallery opening.

Cuarón’s version takes this moment from an uncomfortable but private encounter to a public scene. Finn’s opening is already in full swing when Joe (Chris Cooper) shows up, unannounced and uninvited. Hawke’s Finn is obviously panicked; he stutters, winces, and ineffectually attempts to hustle Joe out of the gallery before he is seen. Cooper plays Joe as warm and well-meaning but ungainly. His voice is pitched too loud, his accent is too broad, and his language too coarse (Finn cringes when Joe jovially calls the Jagger character, Ragno, a ‘sonofabitch’).

Joe stands out visually, too. In a sea of slouchy cashmere sweaters, chic pencil skirts, and wool blazers slung casually over jeans, Joe’s shoddy-looking, too-formal ‘70s-era tuxedo is a sartorial anomaly. One of Cuarón’s strokes of visual genius is the beautiful, strategic use of green – a colour alternately and sometimes simultaneously connoting wealth, envy, and nature – in all the costumes and sets.

Cuarón uses the variety of his colour palette to great advantage in this scene: the gallery-goers run the gambit of rich hunter green to understated khaki to brilliant lime. Again Joe is visually coded as an outsider. Joe’s touch of green in the spearmint ruffles of his tuxedo shirt, is suggestive of nothing more the chewing gum: cheap, tacky and disposable.

Seen through Finn’s eyes, Joe is big, colourful, garish, too much. For half the scene, Cuarón frames Joe in front of a larger-than-life black-and-white portrait of himself. From Finn and the audience’s viewpoint, Joe seems to pop out of the frame, simultaneously diminished and (for Finn, uncomfortably) vital.

Seen through Finn’s eyes, Joe is big, colourful, garish, too much. For half the scene, Cuarón frames Joe in front of a larger-than-life black-and-white portrait of himself. From Finn and the audience’s viewpoint, Joe seems to pop out of the frame, simultaneously diminished and (for Finn, uncomfortably) vital.

The culmination of Finn’s embarrassment is when Joe, gesturing wildly, knocks over a server’s tray of champagne — and then gets down on his hands and knees to help her clean up. The camera reinforces Finn’s view of Joe, filming the scene from above to emphasize Joe’s lowly, crouching position. Finn is mortified. He knows by now it’s the rich and glamorous who make messes; cleaning them up is for everyone else.

The culmination of Finn’s embarrassment is when Joe, gesturing wildly, knocks over a server’s tray of champagne — and then gets down on his hands and knees to help her clean up. The camera reinforces Finn’s view of Joe, filming the scene from above to emphasize Joe’s lowly, crouching position. Finn is mortified. He knows by now it’s the rich and glamorous who make messes; cleaning them up is for everyone else.

Flustered, Finn screams at Joe to “just LEAVE IT!” It’s in this moment that it dawns on Joe with heartbreaking clarity that is presence isn’t welcome. Chris Cooper is absolutely tremendous here; an actor to break your damn heart. You can literally see the realization that he is an embarrassment to Finn cross his face.

Flustered, Finn screams at Joe to “just LEAVE IT!” It’s in this moment that it dawns on Joe with heartbreaking clarity that is presence isn’t welcome. Chris Cooper is absolutely tremendous here; an actor to break your damn heart. You can literally see the realization that he is an embarrassment to Finn cross his face.

Joe quickly leaves and, after a beat, Finn eventually chases him out, but he stops before ever really leaving the gallery. Joe stands outside on the street while Finn stands above him on the staircase. The effect is a camera that elevates Finn and looks down on Joe: Joe is on the outside, looking in and Finn is perched liminally on the doorstep, on his way up.

Joe quickly leaves and, after a beat, Finn eventually chases him out, but he stops before ever really leaving the gallery. Joe stands outside on the street while Finn stands above him on the staircase. The effect is a camera that elevates Finn and looks down on Joe: Joe is on the outside, looking in and Finn is perched liminally on the doorstep, on his way up.

Directed by Brian Kirk and written by Sarah Phelps, the BBC’s 2011 Great Expectations miniseries is, visually and thematically, a dark and, yes, even gritty take on Dickens’ novel, including a visit to a brothel and a rather graphic self-immolation. Phelps’ screenplay hews to the plot and characters of the novel quite closely, but the dialogue is often significantly different; Joe is the character most altered in Phelps’ script. Far from the awkward, occasionally buffoonish, but dignified Joe of the novel and Lean’s film, this Joe is confident, proud, forthcoming with his feelings and opinions, and, in this particular scene, angry.

Like Cuarón, Kirk stages the beginning of this scene in public. Joe surprises Pip at his gentlemen’s club where he is drinking with Herbert Pocket. Shaun Dooley’s physicality immediately marks him as different from the rest of the men in the club. His big, frizzy hair and ruddy cheeks contrast with the dark, languorous curls and pallid skin of Pip and Herbert.

Directed by Brian Kirk and written by Sarah Phelps, the BBC’s 2011 Great Expectations miniseries is, visually and thematically, a dark and, yes, even gritty take on Dickens’ novel, including a visit to a brothel and a rather graphic self-immolation. Phelps’ screenplay hews to the plot and characters of the novel quite closely, but the dialogue is often significantly different; Joe is the character most altered in Phelps’ script. Far from the awkward, occasionally buffoonish, but dignified Joe of the novel and Lean’s film, this Joe is confident, proud, forthcoming with his feelings and opinions, and, in this particular scene, angry.

Like Cuarón, Kirk stages the beginning of this scene in public. Joe surprises Pip at his gentlemen’s club where he is drinking with Herbert Pocket. Shaun Dooley’s physicality immediately marks him as different from the rest of the men in the club. His big, frizzy hair and ruddy cheeks contrast with the dark, languorous curls and pallid skin of Pip and Herbert.

Joe strides into the club, broad shoulders squared, and barks at the porter that he has “no cause to lay hands on me.” Pip, obviously mortified, cannot look Joe in the eye or even speak to him. He all but flees, returning to his flat with Joe following on his heels.

Once behind closed doors the viewer gets a better sense of why, in this version, Joe has come: both to check on Pip and to chastise him. Joe scolds Pip for not writing, even to let them know that he was well; he reminds Pip that his bedridden sister “lives for” news from him. Pip appears not so much unmoved as unwilling to be moved. Throughout this scene Kirk shoots Booth in a series of tight close-ups that emphasize his inability to meet Joe’s eyes.

Joe strides into the club, broad shoulders squared, and barks at the porter that he has “no cause to lay hands on me.” Pip, obviously mortified, cannot look Joe in the eye or even speak to him. He all but flees, returning to his flat with Joe following on his heels.

Once behind closed doors the viewer gets a better sense of why, in this version, Joe has come: both to check on Pip and to chastise him. Joe scolds Pip for not writing, even to let them know that he was well; he reminds Pip that his bedridden sister “lives for” news from him. Pip appears not so much unmoved as unwilling to be moved. Throughout this scene Kirk shoots Booth in a series of tight close-ups that emphasize his inability to meet Joe’s eyes.

The two actors are even physically set at odds. When Joe follows Pip from the club, he is all but chasing him. And when they arrive at Pip’s chambers, they stand facing each other on opposite sides of the frame, looking less like companions than combatants.

The two actors are even physically set at odds. When Joe follows Pip from the club, he is all but chasing him. And when they arrive at Pip’s chambers, they stand facing each other on opposite sides of the frame, looking less like companions than combatants.

Up until this point Joe seems to believe Pip has been careless: that the lack of communication of him has been self-involved but accidental. It is only when they discuss who would even read his letters that Joe realizes the truth. When Joe suggests the petty, officious Pumblechook as the obvious candidate, Pip sneers that Pumblechook only wants to brag that he gave Pip his start in life. Joe shrugs, “He’s an idiot, let him brag. It doesn’t hurt you.” Pip snaps back, “Oh doesn’t it?”

Joe suddenly realizes that Pip is ashamed (“ashamed of me, ashamed of home”) and that that shame is hurting him, very much. It’s at this moment that the Joe of Phelps’ script most strongly evokes the Joe of Dickens’ novel – compassionate, generous, and loving. Because whether or not Pip should feel ashamed is immaterial; the fact of his pain is enough.

Joe’s entire demeanour changes. He softens toward Pip and physically broaches the gap between them. Flustered, Pip responds with the frustrated, deeply-felt cry of every teenager at some point or another: “you don’t understand!” In response, Joe gently gathers Pip’s head in his hands, the kind of embrace reserved for children or the vulnerable and distraught. Instead of the blessing of Dickens’ text, here Joe kisses Pip on the forehand and whispers “I understand.”

Up until this point Joe seems to believe Pip has been careless: that the lack of communication of him has been self-involved but accidental. It is only when they discuss who would even read his letters that Joe realizes the truth. When Joe suggests the petty, officious Pumblechook as the obvious candidate, Pip sneers that Pumblechook only wants to brag that he gave Pip his start in life. Joe shrugs, “He’s an idiot, let him brag. It doesn’t hurt you.” Pip snaps back, “Oh doesn’t it?”

Joe suddenly realizes that Pip is ashamed (“ashamed of me, ashamed of home”) and that that shame is hurting him, very much. It’s at this moment that the Joe of Phelps’ script most strongly evokes the Joe of Dickens’ novel – compassionate, generous, and loving. Because whether or not Pip should feel ashamed is immaterial; the fact of his pain is enough.

Joe’s entire demeanour changes. He softens toward Pip and physically broaches the gap between them. Flustered, Pip responds with the frustrated, deeply-felt cry of every teenager at some point or another: “you don’t understand!” In response, Joe gently gathers Pip’s head in his hands, the kind of embrace reserved for children or the vulnerable and distraught. Instead of the blessing of Dickens’ text, here Joe kisses Pip on the forehand and whispers “I understand.”

**********

The final thing I want to examine in these three scenes is the last thing Joe says to Pip before he leaves. Each film gives Joe a different parting line suited to the audience but the sentiment – reassurance, benevolence and love – remains the same.

In the David Lean adaptation, aimed at an audience who had likely lived through Depression and at least one war, Joe’s last line in this scene is taken straight from Dickens’ text: “God bless you.” Lean’s audience would recognize this as an invocation, a benediction, and a call for protection, not just for Pip’s body but his immortal soul.

In Alfonso Cuarón’s Gen-X modernization, when the line is being delivered to the Hollywood poster boy of the slacker generation, the line becomes “I’m proud of you, Finn. I always have been.” For the 2011 adaptation Sarah Phelps was insistent on casting Pip young to show “somebody finding their feet as an adult, dealing with growing up.” The result is a Great Expectations starring (and presumably geared toward) that much-discussed, oft-derided but rarely truly understood commodity: a millennial. And in this case Joe’s last line becomes an emphatic, comforting “I understand.”

This, to me, is what makes adaptations are so fascinating. Stories like Great Expectations persist because they manage to be both robust and infinitely malleable. They can be shaped and tweaked into something fresh and urgent all while remaining undeniably, irrefutably themselves.

**********

The final thing I want to examine in these three scenes is the last thing Joe says to Pip before he leaves. Each film gives Joe a different parting line suited to the audience but the sentiment – reassurance, benevolence and love – remains the same.

In the David Lean adaptation, aimed at an audience who had likely lived through Depression and at least one war, Joe’s last line in this scene is taken straight from Dickens’ text: “God bless you.” Lean’s audience would recognize this as an invocation, a benediction, and a call for protection, not just for Pip’s body but his immortal soul.

In Alfonso Cuarón’s Gen-X modernization, when the line is being delivered to the Hollywood poster boy of the slacker generation, the line becomes “I’m proud of you, Finn. I always have been.” For the 2011 adaptation Sarah Phelps was insistent on casting Pip young to show “somebody finding their feet as an adult, dealing with growing up.” The result is a Great Expectations starring (and presumably geared toward) that much-discussed, oft-derided but rarely truly understood commodity: a millennial. And in this case Joe’s last line becomes an emphatic, comforting “I understand.”

This, to me, is what makes adaptations are so fascinating. Stories like Great Expectations persist because they manage to be both robust and infinitely malleable. They can be shaped and tweaked into something fresh and urgent all while remaining undeniably, irrefutably themselves.