Anatomy of a Scene: Jane Eyre’s Red Room

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

While we at the Riot take some time off to rest and catch up on our reading, we’re re-running some of our favorite posts from the last several months. Enjoy our highlight reel, and we’ll be back with new stuff on Monday, January 11th.

This post originally ran September 15, 2015.

_________________________

As a general rule I love adaptations, from the faithful to the experimental to the “it’s actually just the name you’re using, right?” I’m interested in the stories we choose to tell and retell across mediums, but I’m fascinated by examining the ways in which we choose to retell them. It can be a bit unwieldy (especially in blog form!) to compare whole books to entire films or television series, so there I thought I’d try something different with a close read of a single scene across three adaptations.

The natural choice of book was one of my favourites and one of the most frequently adapted classic English novels – Jane Eyre. There are no shortage of scenes in Jane Eyre that are rich for directorial interpretation, but I chose the red room scene.

A quick refresher for those who need it: the red room scene takes place in the second chapter of the novel. When, at the end of chapter one, Jane defends herself against her cousin John Reed’s beating, Jane’s Aunt Reed punishes her by locking her in what Jane calls “the red room.” The red room is the room in which Aunt Reed’s husband, Jane’s biological uncle, died; unsurprisingly, Jane and her cousins believe it to be haunted. Once in the red room Jane initially focuses on the injustice of her imprisonment, but soon becomes frightened when she begins to imagine that the displeasure her uncle Reed might feel upon learning of his sister’s child’s mistreatment at his family’s hands could cause him to rise from the dead. Jane sees strange flashing beams of light, and becomes so consumed by fear that she has a “fit’ and loses consciousness.

I chose the red room scene because it has always seemed to me to be a sort of litmus test for how the rest of an adaptation of Jane Eyre will proceed. In other words, as goes the red room scene, so goes the film.

For one thing, it’s a scene that focuses exclusively on Jane; it’s part of her history and character development before she even meets Rochester. Some earlier adaptations, such as the 1944 film starring Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles or the 1970 film starring Susannah York and George C. Scott. eschew the red room scene altogether. That an adaptation chooses to include the scene at all suggests that, at least to a certain extent, it reads the novel as a Bildungsroman rather than a romance.

This scene also provides perfect snapshot of Jane’s essential character: spirited, solitary, righteously indignant, sensitive, and ultimately undone by her own feelings and imagination. Which parts of Jane are emphasized in this scene on film can often set the tone for how she will be portrayed as an adult.

Finally, this scene includes one of the more difficult-to-wrangle elements of the novel: Charlotte Brontë’s Gothic suggestions of the supernatural. These includes the flashes of lights that Jane sees, as well as the moment of pathetic fallacy when lightning ominously strikes a tree just as Rochester makes his doomed proposal to Jane, and the moment when, from across the country, Jane hears Rochester crying her name as he tries to escape a burning Thornfield. Ignore them, explain them, or amplify them, these moments demand a stance and the red room scene typically provides a good indication of which one a director will take.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll be looking at three adaptations: the 1996 film directed by Franco Zeffirelli, the 2006 BBC/Masterpiece Theatre mini-series directed by Susannah White, and the 2011 film by Cary Fukunaga. They’re three of the most currently popular, easily-available adaptations of Jane Eyre with diverse directors who offer three fairly distinct takes.

Zeffirelli’s film actually begins with the red room scene, even before the credits have rolled. The scene’s context – Jane’s discovery and subsequent beating by John – is omitted entirely; the first we see of Jane is her being yanked and punched by all three of her cousins at once. Not only does Jane not defend herself, she barely resists. While seemingly minor – after all, there is a lot of Reed cruelty to chose from – this moment in the novel has fairly significant implications for Jane’s character. It shows that despite her disadvantages of stature and station, she has spirit, courage, and an immutable sense of fairness. Without this, Jane appears less angry and more passive, a version of her that is born out in this film by Charlotte Gainsborough’s measured, almost muted performance as the adult Jane.

The room Jane is thrown into is not named by either Jane or Aunt Reed in this film, but there’s no mistaking it: it’s red walls, scarlet damask wallpaper, and crimson upholstery as far as the eye can see. The set here is pure gothic – simultaneously dark and lurid. It’s also utterly in keeping with Zeffirelli’s lush, almost baroque visuals and colour-saturated aesthetic.

The closest the viewer get to an explanation of why Jane fears the red room is when she pleads to her aunt (in a line taken directly from the book) that she “cannot endure it”; there is no suggestion of the spectral. This too, is consistent with the rest of the film, which excises Brontë’s supernatural touches.

The room Jane is thrown into is not named by either Jane or Aunt Reed in this film, but there’s no mistaking it: it’s red walls, scarlet damask wallpaper, and crimson upholstery as far as the eye can see. The set here is pure gothic – simultaneously dark and lurid. It’s also utterly in keeping with Zeffirelli’s lush, almost baroque visuals and colour-saturated aesthetic.

The closest the viewer get to an explanation of why Jane fears the red room is when she pleads to her aunt (in a line taken directly from the book) that she “cannot endure it”; there is no suggestion of the spectral. This too, is consistent with the rest of the film, which excises Brontë’s supernatural touches.

What the film does offer, however, are some neat pieces of camera work that enhance the atmosphere of lurid creepiness. When Aunt Reed throws Jane into the red room, she throws her up against a large, full-length mirror causing it to swing wildly. The mirror not only reflects and doubles the overwhelming redness, the motion it as it swings also gives the subtle impression of parts of the room advancing and retreating. Of course, the viewer understands what is creating this sensory chaos; we’re behind the curtain the whole time.

At this point the camera drops down and pans wildly across the room, briefly giving us Jane’s perspective. While the camera offers the viewer Jane’s point of view, its return to normal perspective actually highlights the difference and the distance between the viewer and Jane; we were seeing through her eyes, and now we are not. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the set, blocking, and camera work as much as it is to Jane.

What the film does offer, however, are some neat pieces of camera work that enhance the atmosphere of lurid creepiness. When Aunt Reed throws Jane into the red room, she throws her up against a large, full-length mirror causing it to swing wildly. The mirror not only reflects and doubles the overwhelming redness, the motion it as it swings also gives the subtle impression of parts of the room advancing and retreating. Of course, the viewer understands what is creating this sensory chaos; we’re behind the curtain the whole time.

At this point the camera drops down and pans wildly across the room, briefly giving us Jane’s perspective. While the camera offers the viewer Jane’s point of view, its return to normal perspective actually highlights the difference and the distance between the viewer and Jane; we were seeing through her eyes, and now we are not. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the set, blocking, and camera work as much as it is to Jane.

In a similar vein, for the final few shots of the scene the mirror itself is takes up almost as much of the frame as Jane does, literally decentering Jane and giving equal weight to the effect created by the mirror. Overall the scene is consistent with Zeffirelli’s vision for Jane Eyre, one that prioritizes image and atmosphere over dialogue and character: direction over story.

Susannah White’s 2006 BBC/Masterpiece Theatre mini-series takes an entirely different tack, playing the sensational and the supernatural to the hilt with dramatic lighting, crazy camera angles and staring reanimated corpses. Consider Aunt Reed as she exiles Jane to the red room: she is shot in the kind of tight closeup and looming upward angle reserved for monsters in old creature feature films, suggesting that that is exactly how Jane sees her.

In a similar vein, for the final few shots of the scene the mirror itself is takes up almost as much of the frame as Jane does, literally decentering Jane and giving equal weight to the effect created by the mirror. Overall the scene is consistent with Zeffirelli’s vision for Jane Eyre, one that prioritizes image and atmosphere over dialogue and character: direction over story.

Susannah White’s 2006 BBC/Masterpiece Theatre mini-series takes an entirely different tack, playing the sensational and the supernatural to the hilt with dramatic lighting, crazy camera angles and staring reanimated corpses. Consider Aunt Reed as she exiles Jane to the red room: she is shot in the kind of tight closeup and looming upward angle reserved for monsters in old creature feature films, suggesting that that is exactly how Jane sees her.

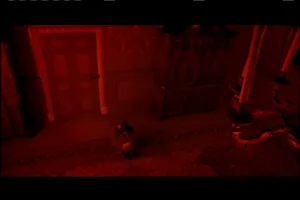

The lighting, camerawork and script in White’s red room scene don’t necessarily show what is happening but how what happening feels to Jane. In this red room, it isn’t that the walls or tapestries or carpets are red, it’s that everything seems red. The entire screen is awash in a garish, blood-red filter, which, combined with the darkness of the scene, give it an almost darkroom effect. At one point the camera looks down on a sitting Jane from above but rather than creating distance, this shot, followed immediately by a tight closeup of Jane weeping, has the effect of simulating for the viewer the oppressiveness Jane feels.

The lighting, camerawork and script in White’s red room scene don’t necessarily show what is happening but how what happening feels to Jane. In this red room, it isn’t that the walls or tapestries or carpets are red, it’s that everything seems red. The entire screen is awash in a garish, blood-red filter, which, combined with the darkness of the scene, give it an almost darkroom effect. At one point the camera looks down on a sitting Jane from above but rather than creating distance, this shot, followed immediately by a tight closeup of Jane weeping, has the effect of simulating for the viewer the oppressiveness Jane feels.

As in the Zeffirelli version, this Jane is immediately frightened of the room rather than talking herself into it, but unlike the Zeffirelli film, White’s script explicitly states why Jane is afraid. Jane begs her uncle “please don’t come back” and, not content with the flashing beams of light described in the novel, White provides another retro-horror moment when the undead body of Uncle Reed rises from his bed as lightning strikes. Making the suggestion of the supernatural textually explicit is consistent with the approach of the rest of the film (which has lightning striking dramatically out of a clear sky at Rochester’s proposal and which later suggests, via slo-mo closeups of a forest stream, that Rochester’s voice is carried to Jane from Thornfield by the countryside itself).

As in the Zeffirelli version, this Jane is immediately frightened of the room rather than talking herself into it, but unlike the Zeffirelli film, White’s script explicitly states why Jane is afraid. Jane begs her uncle “please don’t come back” and, not content with the flashing beams of light described in the novel, White provides another retro-horror moment when the undead body of Uncle Reed rises from his bed as lightning strikes. Making the suggestion of the supernatural textually explicit is consistent with the approach of the rest of the film (which has lightning striking dramatically out of a clear sky at Rochester’s proposal and which later suggests, via slo-mo closeups of a forest stream, that Rochester’s voice is carried to Jane from Thornfield by the countryside itself).

This moment of reanimation again replicates for the viewer how Jane feels. Here we never literally seeing the red room from Jane’s perspective, but we are experiencing the room as she experiences it. These somewhat melodramatic choices might make White’s a less elegant adaptation, but they consistently center Jane’s perception and experience. This continues throughout the miniseries – White gives a lot of time and space for Jane’s development outside of her relationship with Rochester. This series even explicitly positions itself about Jane’s adventures by opening with a whimsical, original scene prior to the red room that represents Jane reading by inserting her into the desert landscape of her book. Of all three directors, White does the most to replicate the immediate and personal feel of the novel’s first-person narration (without resorting to voiceover).

This moment of reanimation again replicates for the viewer how Jane feels. Here we never literally seeing the red room from Jane’s perspective, but we are experiencing the room as she experiences it. These somewhat melodramatic choices might make White’s a less elegant adaptation, but they consistently center Jane’s perception and experience. This continues throughout the miniseries – White gives a lot of time and space for Jane’s development outside of her relationship with Rochester. This series even explicitly positions itself about Jane’s adventures by opening with a whimsical, original scene prior to the red room that represents Jane reading by inserting her into the desert landscape of her book. Of all three directors, White does the most to replicate the immediate and personal feel of the novel’s first-person narration (without resorting to voiceover).

Finally, unlike Zeffirelli’s film this adaptation does present the conflict between Jane and John, and Jane fighting back (with gusto). In a similar vein, White does not show Jane fainting in the red room; the last we see of her she is pounding the door of the red room with her fists. When we next see Jane, she is fully awake and has her hands wrapped in bandages reminiscent of a boxer’s. This is a more spirited Jane that is consistent with the hot-blooded (some might even say bodice-heaving) tone of the mini-series and Ruth Wilson’s passionate performance as adult Jane.

Cary Fukunaga presents the most restrained iteration of the red room scene yet. Like Zeffirelli, Fukunaga is working with a distinct, consistent colour palette, but while the former skews dark and autumnal, Fukunaga favours a dreamy, bleached-out, shades-of-grey aesthetic. In Fukunaga’s red room, the walls are crimson damask and there are a few brick-red linens, but overall the room has as much cream as red. This red room is also much more brightly lit than either of the previous two; it’s daytime when Jane is locked in there, and there are plenty of windows letting in the natural light.

Finally, unlike Zeffirelli’s film this adaptation does present the conflict between Jane and John, and Jane fighting back (with gusto). In a similar vein, White does not show Jane fainting in the red room; the last we see of her she is pounding the door of the red room with her fists. When we next see Jane, she is fully awake and has her hands wrapped in bandages reminiscent of a boxer’s. This is a more spirited Jane that is consistent with the hot-blooded (some might even say bodice-heaving) tone of the mini-series and Ruth Wilson’s passionate performance as adult Jane.

Cary Fukunaga presents the most restrained iteration of the red room scene yet. Like Zeffirelli, Fukunaga is working with a distinct, consistent colour palette, but while the former skews dark and autumnal, Fukunaga favours a dreamy, bleached-out, shades-of-grey aesthetic. In Fukunaga’s red room, the walls are crimson damask and there are a few brick-red linens, but overall the room has as much cream as red. This red room is also much more brightly lit than either of the previous two; it’s daytime when Jane is locked in there, and there are plenty of windows letting in the natural light.

Like White’s adaptation, this version offers an explanation of why Jane is afraid, albeit one that is slightly different from that of the novel. As Jane is being dragged into the room, we hear her protest that it is “haunted,” and the maids that are locking her in there tell her to be good or (in another line taken almost verbatim from the novel) “something will come down and fetch you.”

Here it is a general suggestion of hauntedness rather than a specific fear of her uncle Reed’s ghost that causes Jane to panic. As she beats furiously on the door, a large puff of black smoke (which the viewer might infer to be caused an animal in the chimney or perhaps the flue opening) bursts out of the fireplace. This turns Jane’s fear to frenzy and she runs at the door so hard that she hits her head on it, knocking herself out cold.

Like White’s adaptation, this version offers an explanation of why Jane is afraid, albeit one that is slightly different from that of the novel. As Jane is being dragged into the room, we hear her protest that it is “haunted,” and the maids that are locking her in there tell her to be good or (in another line taken almost verbatim from the novel) “something will come down and fetch you.”

Here it is a general suggestion of hauntedness rather than a specific fear of her uncle Reed’s ghost that causes Jane to panic. As she beats furiously on the door, a large puff of black smoke (which the viewer might infer to be caused an animal in the chimney or perhaps the flue opening) bursts out of the fireplace. This turns Jane’s fear to frenzy and she runs at the door so hard that she hits her head on it, knocking herself out cold.

This moment is in keeping with Fukunaga’s choice not necessarily to completely eliminate Brontë’s supernatural Gothic touches, but to provide a rational explanation for them. For example, later in the film when Jane “hears” Rochester calling her name, what is is actually hearing is a kind of internal echo, prompted by St. John angrily saying her name while accusing her of thinking of Rochester.

The bright lighting, a more realistically red set, and the explanations suggested for what frightened Jane and caused her to lose consciousness, all contribute to a grounded, clear-eyed iteration of scene that encourages the viewer to witness Jane’s fear but not necessarily to share it: to feel for her but not as her. It’s appropriate for a film with a very Victorian directorial sensibility – beautiful, deeply-felt but restrained.

So there you have it: one book, three adaptations, and three takes on an iconic scene, all utterly different and yet in their own way faithful to the source material.

This moment is in keeping with Fukunaga’s choice not necessarily to completely eliminate Brontë’s supernatural Gothic touches, but to provide a rational explanation for them. For example, later in the film when Jane “hears” Rochester calling her name, what is is actually hearing is a kind of internal echo, prompted by St. John angrily saying her name while accusing her of thinking of Rochester.

The bright lighting, a more realistically red set, and the explanations suggested for what frightened Jane and caused her to lose consciousness, all contribute to a grounded, clear-eyed iteration of scene that encourages the viewer to witness Jane’s fear but not necessarily to share it: to feel for her but not as her. It’s appropriate for a film with a very Victorian directorial sensibility – beautiful, deeply-felt but restrained.

So there you have it: one book, three adaptations, and three takes on an iconic scene, all utterly different and yet in their own way faithful to the source material.

The room Jane is thrown into is not named by either Jane or Aunt Reed in this film, but there’s no mistaking it: it’s red walls, scarlet damask wallpaper, and crimson upholstery as far as the eye can see. The set here is pure gothic – simultaneously dark and lurid. It’s also utterly in keeping with Zeffirelli’s lush, almost baroque visuals and colour-saturated aesthetic.

The closest the viewer get to an explanation of why Jane fears the red room is when she pleads to her aunt (in a line taken directly from the book) that she “cannot endure it”; there is no suggestion of the spectral. This too, is consistent with the rest of the film, which excises Brontë’s supernatural touches.

The room Jane is thrown into is not named by either Jane or Aunt Reed in this film, but there’s no mistaking it: it’s red walls, scarlet damask wallpaper, and crimson upholstery as far as the eye can see. The set here is pure gothic – simultaneously dark and lurid. It’s also utterly in keeping with Zeffirelli’s lush, almost baroque visuals and colour-saturated aesthetic.

The closest the viewer get to an explanation of why Jane fears the red room is when she pleads to her aunt (in a line taken directly from the book) that she “cannot endure it”; there is no suggestion of the spectral. This too, is consistent with the rest of the film, which excises Brontë’s supernatural touches.

What the film does offer, however, are some neat pieces of camera work that enhance the atmosphere of lurid creepiness. When Aunt Reed throws Jane into the red room, she throws her up against a large, full-length mirror causing it to swing wildly. The mirror not only reflects and doubles the overwhelming redness, the motion it as it swings also gives the subtle impression of parts of the room advancing and retreating. Of course, the viewer understands what is creating this sensory chaos; we’re behind the curtain the whole time.

At this point the camera drops down and pans wildly across the room, briefly giving us Jane’s perspective. While the camera offers the viewer Jane’s point of view, its return to normal perspective actually highlights the difference and the distance between the viewer and Jane; we were seeing through her eyes, and now we are not. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the set, blocking, and camera work as much as it is to Jane.

What the film does offer, however, are some neat pieces of camera work that enhance the atmosphere of lurid creepiness. When Aunt Reed throws Jane into the red room, she throws her up against a large, full-length mirror causing it to swing wildly. The mirror not only reflects and doubles the overwhelming redness, the motion it as it swings also gives the subtle impression of parts of the room advancing and retreating. Of course, the viewer understands what is creating this sensory chaos; we’re behind the curtain the whole time.

At this point the camera drops down and pans wildly across the room, briefly giving us Jane’s perspective. While the camera offers the viewer Jane’s point of view, its return to normal perspective actually highlights the difference and the distance between the viewer and Jane; we were seeing through her eyes, and now we are not. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the set, blocking, and camera work as much as it is to Jane.

In a similar vein, for the final few shots of the scene the mirror itself is takes up almost as much of the frame as Jane does, literally decentering Jane and giving equal weight to the effect created by the mirror. Overall the scene is consistent with Zeffirelli’s vision for Jane Eyre, one that prioritizes image and atmosphere over dialogue and character: direction over story.

Susannah White’s 2006 BBC/Masterpiece Theatre mini-series takes an entirely different tack, playing the sensational and the supernatural to the hilt with dramatic lighting, crazy camera angles and staring reanimated corpses. Consider Aunt Reed as she exiles Jane to the red room: she is shot in the kind of tight closeup and looming upward angle reserved for monsters in old creature feature films, suggesting that that is exactly how Jane sees her.

In a similar vein, for the final few shots of the scene the mirror itself is takes up almost as much of the frame as Jane does, literally decentering Jane and giving equal weight to the effect created by the mirror. Overall the scene is consistent with Zeffirelli’s vision for Jane Eyre, one that prioritizes image and atmosphere over dialogue and character: direction over story.

Susannah White’s 2006 BBC/Masterpiece Theatre mini-series takes an entirely different tack, playing the sensational and the supernatural to the hilt with dramatic lighting, crazy camera angles and staring reanimated corpses. Consider Aunt Reed as she exiles Jane to the red room: she is shot in the kind of tight closeup and looming upward angle reserved for monsters in old creature feature films, suggesting that that is exactly how Jane sees her.

The lighting, camerawork and script in White’s red room scene don’t necessarily show what is happening but how what happening feels to Jane. In this red room, it isn’t that the walls or tapestries or carpets are red, it’s that everything seems red. The entire screen is awash in a garish, blood-red filter, which, combined with the darkness of the scene, give it an almost darkroom effect. At one point the camera looks down on a sitting Jane from above but rather than creating distance, this shot, followed immediately by a tight closeup of Jane weeping, has the effect of simulating for the viewer the oppressiveness Jane feels.

The lighting, camerawork and script in White’s red room scene don’t necessarily show what is happening but how what happening feels to Jane. In this red room, it isn’t that the walls or tapestries or carpets are red, it’s that everything seems red. The entire screen is awash in a garish, blood-red filter, which, combined with the darkness of the scene, give it an almost darkroom effect. At one point the camera looks down on a sitting Jane from above but rather than creating distance, this shot, followed immediately by a tight closeup of Jane weeping, has the effect of simulating for the viewer the oppressiveness Jane feels.

As in the Zeffirelli version, this Jane is immediately frightened of the room rather than talking herself into it, but unlike the Zeffirelli film, White’s script explicitly states why Jane is afraid. Jane begs her uncle “please don’t come back” and, not content with the flashing beams of light described in the novel, White provides another retro-horror moment when the undead body of Uncle Reed rises from his bed as lightning strikes. Making the suggestion of the supernatural textually explicit is consistent with the approach of the rest of the film (which has lightning striking dramatically out of a clear sky at Rochester’s proposal and which later suggests, via slo-mo closeups of a forest stream, that Rochester’s voice is carried to Jane from Thornfield by the countryside itself).

As in the Zeffirelli version, this Jane is immediately frightened of the room rather than talking herself into it, but unlike the Zeffirelli film, White’s script explicitly states why Jane is afraid. Jane begs her uncle “please don’t come back” and, not content with the flashing beams of light described in the novel, White provides another retro-horror moment when the undead body of Uncle Reed rises from his bed as lightning strikes. Making the suggestion of the supernatural textually explicit is consistent with the approach of the rest of the film (which has lightning striking dramatically out of a clear sky at Rochester’s proposal and which later suggests, via slo-mo closeups of a forest stream, that Rochester’s voice is carried to Jane from Thornfield by the countryside itself).

This moment of reanimation again replicates for the viewer how Jane feels. Here we never literally seeing the red room from Jane’s perspective, but we are experiencing the room as she experiences it. These somewhat melodramatic choices might make White’s a less elegant adaptation, but they consistently center Jane’s perception and experience. This continues throughout the miniseries – White gives a lot of time and space for Jane’s development outside of her relationship with Rochester. This series even explicitly positions itself about Jane’s adventures by opening with a whimsical, original scene prior to the red room that represents Jane reading by inserting her into the desert landscape of her book. Of all three directors, White does the most to replicate the immediate and personal feel of the novel’s first-person narration (without resorting to voiceover).

This moment of reanimation again replicates for the viewer how Jane feels. Here we never literally seeing the red room from Jane’s perspective, but we are experiencing the room as she experiences it. These somewhat melodramatic choices might make White’s a less elegant adaptation, but they consistently center Jane’s perception and experience. This continues throughout the miniseries – White gives a lot of time and space for Jane’s development outside of her relationship with Rochester. This series even explicitly positions itself about Jane’s adventures by opening with a whimsical, original scene prior to the red room that represents Jane reading by inserting her into the desert landscape of her book. Of all three directors, White does the most to replicate the immediate and personal feel of the novel’s first-person narration (without resorting to voiceover).

Finally, unlike Zeffirelli’s film this adaptation does present the conflict between Jane and John, and Jane fighting back (with gusto). In a similar vein, White does not show Jane fainting in the red room; the last we see of her she is pounding the door of the red room with her fists. When we next see Jane, she is fully awake and has her hands wrapped in bandages reminiscent of a boxer’s. This is a more spirited Jane that is consistent with the hot-blooded (some might even say bodice-heaving) tone of the mini-series and Ruth Wilson’s passionate performance as adult Jane.

Cary Fukunaga presents the most restrained iteration of the red room scene yet. Like Zeffirelli, Fukunaga is working with a distinct, consistent colour palette, but while the former skews dark and autumnal, Fukunaga favours a dreamy, bleached-out, shades-of-grey aesthetic. In Fukunaga’s red room, the walls are crimson damask and there are a few brick-red linens, but overall the room has as much cream as red. This red room is also much more brightly lit than either of the previous two; it’s daytime when Jane is locked in there, and there are plenty of windows letting in the natural light.

Finally, unlike Zeffirelli’s film this adaptation does present the conflict between Jane and John, and Jane fighting back (with gusto). In a similar vein, White does not show Jane fainting in the red room; the last we see of her she is pounding the door of the red room with her fists. When we next see Jane, she is fully awake and has her hands wrapped in bandages reminiscent of a boxer’s. This is a more spirited Jane that is consistent with the hot-blooded (some might even say bodice-heaving) tone of the mini-series and Ruth Wilson’s passionate performance as adult Jane.

Cary Fukunaga presents the most restrained iteration of the red room scene yet. Like Zeffirelli, Fukunaga is working with a distinct, consistent colour palette, but while the former skews dark and autumnal, Fukunaga favours a dreamy, bleached-out, shades-of-grey aesthetic. In Fukunaga’s red room, the walls are crimson damask and there are a few brick-red linens, but overall the room has as much cream as red. This red room is also much more brightly lit than either of the previous two; it’s daytime when Jane is locked in there, and there are plenty of windows letting in the natural light.

Like White’s adaptation, this version offers an explanation of why Jane is afraid, albeit one that is slightly different from that of the novel. As Jane is being dragged into the room, we hear her protest that it is “haunted,” and the maids that are locking her in there tell her to be good or (in another line taken almost verbatim from the novel) “something will come down and fetch you.”

Here it is a general suggestion of hauntedness rather than a specific fear of her uncle Reed’s ghost that causes Jane to panic. As she beats furiously on the door, a large puff of black smoke (which the viewer might infer to be caused an animal in the chimney or perhaps the flue opening) bursts out of the fireplace. This turns Jane’s fear to frenzy and she runs at the door so hard that she hits her head on it, knocking herself out cold.

Like White’s adaptation, this version offers an explanation of why Jane is afraid, albeit one that is slightly different from that of the novel. As Jane is being dragged into the room, we hear her protest that it is “haunted,” and the maids that are locking her in there tell her to be good or (in another line taken almost verbatim from the novel) “something will come down and fetch you.”

Here it is a general suggestion of hauntedness rather than a specific fear of her uncle Reed’s ghost that causes Jane to panic. As she beats furiously on the door, a large puff of black smoke (which the viewer might infer to be caused an animal in the chimney or perhaps the flue opening) bursts out of the fireplace. This turns Jane’s fear to frenzy and she runs at the door so hard that she hits her head on it, knocking herself out cold.

This moment is in keeping with Fukunaga’s choice not necessarily to completely eliminate Brontë’s supernatural Gothic touches, but to provide a rational explanation for them. For example, later in the film when Jane “hears” Rochester calling her name, what is is actually hearing is a kind of internal echo, prompted by St. John angrily saying her name while accusing her of thinking of Rochester.

The bright lighting, a more realistically red set, and the explanations suggested for what frightened Jane and caused her to lose consciousness, all contribute to a grounded, clear-eyed iteration of scene that encourages the viewer to witness Jane’s fear but not necessarily to share it: to feel for her but not as her. It’s appropriate for a film with a very Victorian directorial sensibility – beautiful, deeply-felt but restrained.

So there you have it: one book, three adaptations, and three takes on an iconic scene, all utterly different and yet in their own way faithful to the source material.

This moment is in keeping with Fukunaga’s choice not necessarily to completely eliminate Brontë’s supernatural Gothic touches, but to provide a rational explanation for them. For example, later in the film when Jane “hears” Rochester calling her name, what is is actually hearing is a kind of internal echo, prompted by St. John angrily saying her name while accusing her of thinking of Rochester.

The bright lighting, a more realistically red set, and the explanations suggested for what frightened Jane and caused her to lose consciousness, all contribute to a grounded, clear-eyed iteration of scene that encourages the viewer to witness Jane’s fear but not necessarily to share it: to feel for her but not as her. It’s appropriate for a film with a very Victorian directorial sensibility – beautiful, deeply-felt but restrained.

So there you have it: one book, three adaptations, and three takes on an iconic scene, all utterly different and yet in their own way faithful to the source material.