Librarians Under Pandemic Duress: Layoffs, Napkin Masks, and Fear of Retaliation

For institutions ranked among the most trustworthy and beloved, it’s shameful how the individuals who comprise libraries are treated as disposable.

As the pandemic lurches forward, more and more libraries are doing something unexpected during a period of time when the digital services they provide are vital: they’re laying off workers or pushing them into alternate emergency jobs for which they’re untrained or unqualified. Librarians in Hennepin County, Minnesota, were told they could be assigned to work in hotel-based homeless shelters, while other systems nationwide like Cuyahoga County, Ohio, laid off or furloughed hundreds of their employees.

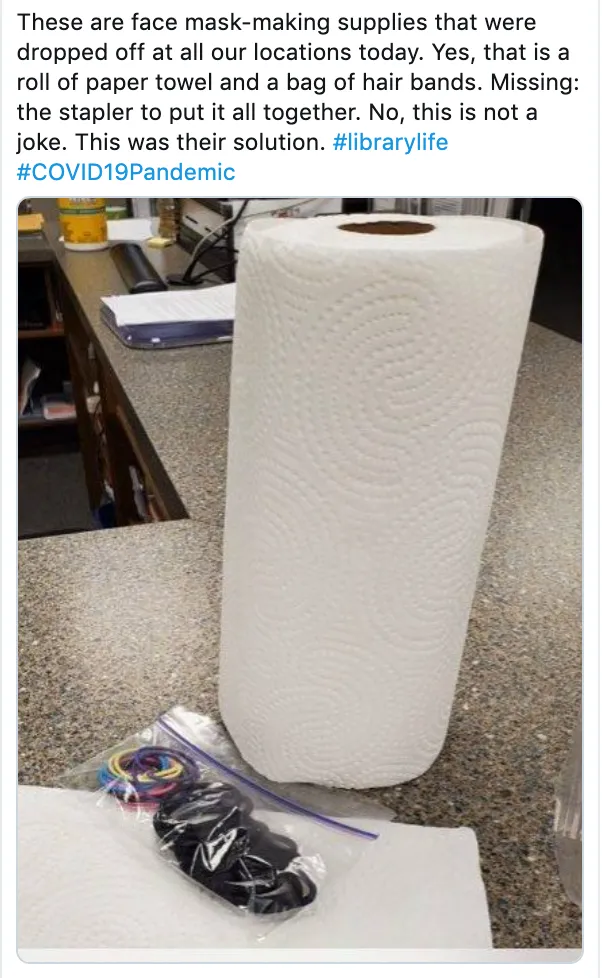

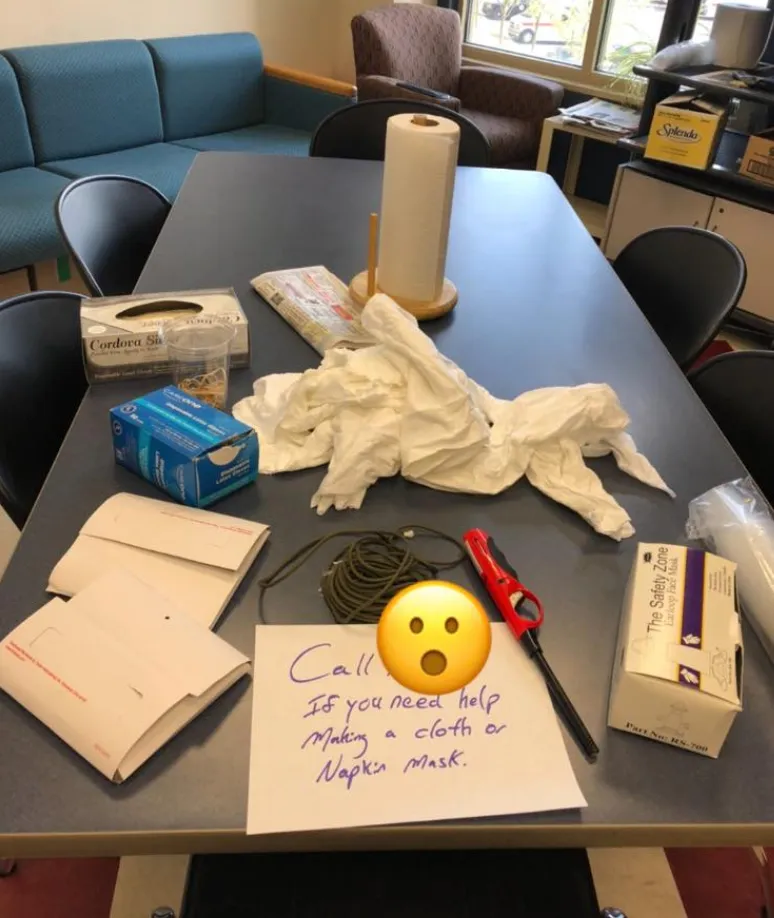

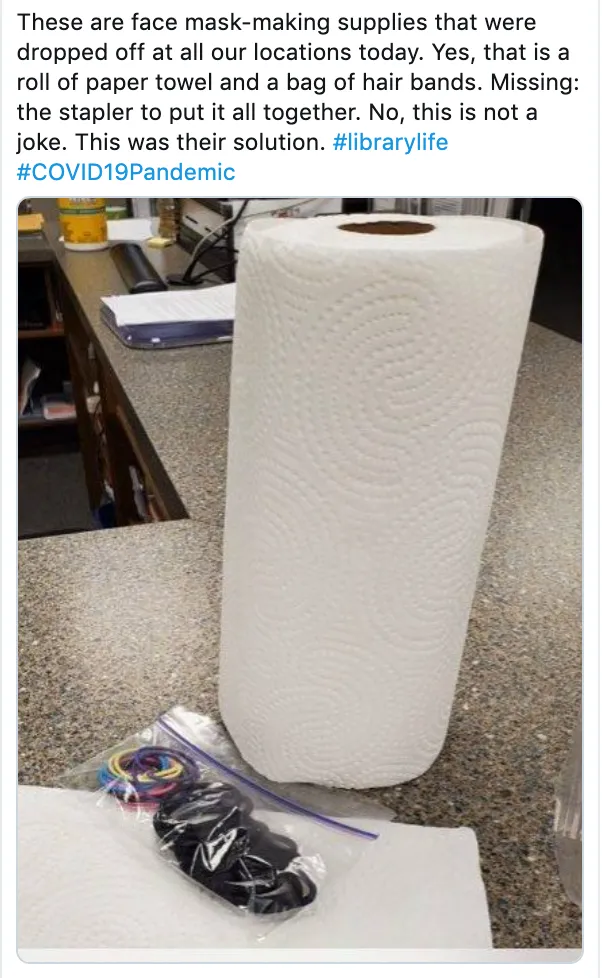

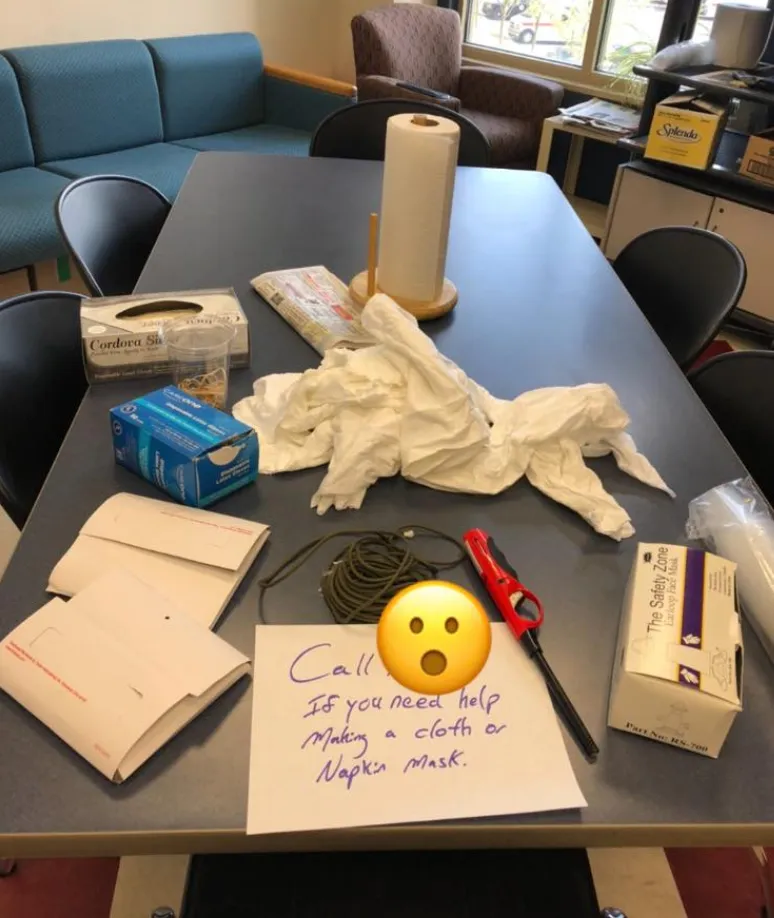

In libraries that are still operating, things aren’t business as usual, either. Some libraries have their staff working entirely from home, while others have their doors shut to the public but are having staff report. Those operating with staff in the building run the gamut in terms of what they’ve provided their employees in terms of health and safety protection. Some have masks available, while others have simply dropped materials like paper towels, tissue, and other poor substitutions for cotton masks and expected employees to make do.

In still other cases, staff who aren’t comfortable in the library are told they’re required to report and if they don’t feel okay doing so, they need to use paid time off (PTO). Libraries that depend upon the hard work of those who aren’t full time, like many institutions, don’t offer PTO or other benefits to those workers. This puts lives on the line as employees choose between their health and that of their loved ones or their job and source of income.

“Library workers do not have labor-oriented organizations fighting for improved working conditions for them; our national professional organization does not serve that role and by extension nor do our state associations,” said Callan Bignoli, Library Director at Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. “This has never been more clear than it is right now.”

Vocational awe in libraries is a consistent reality, as are the ever-present worries regarding funding. Libraries, particularly public institutions, face regular threats of cuts to their budgets, and thus strive to prove their role as essential services to their communities. The fear of job cuts is real and, as is being seen broadly throughout the U.S. and Canada, happening right before our eyes.

These cuts are likely no small part of why libraries are scrambling to cobble together reopening plans. The plans range from moderately plausible, like those which suggest COVID-19 testing for all staff (with what tests?), to downright dangerous and discriminatory (a plan from East Lansing Public Library in Michigan, sent out to a public listserv for librarians, suggests sending home anyone with a temperature of 99 or higher, a failure to understand how human bodies work—99 is an average temperature for some bodies—among other glaring issues such as not addressing whether those staff will be compensated). None of the plans address sociopolitical realities like the fear Black people have in covering their faces and the challenges lived by the economically disadvantaged—can this vulnerable group get to the library? What about access to face masks?

Given that many public libraries are funded annually and have their budget already in place for the year, the swift pace of layoffs and furloughs is especially surprising. Certainly city budgets will be impacted by lost tax revenue, among other sources, but given the vital role public libraries are playing in providing accurate information and entertainment to their communities at a time when they’re most in need of both, cutting staff now appears ill-conceived and, perhaps, too quick.

“In news articles decision-makers have given a number of different reasons for these decisions, from perceived budget cuts to not believing that library workers can work from home,” said one librarian-advocate who preferred not to be named. “And it’s not just public libraries. Academic, museum, and school libraries are seeing layoffs and furloughs too, most likely because of perceived budget cuts and strains on funding.”

Optics play a role here, too. Those making these cuts believe that library staff working from home may appear to not be working and are still being paid. This, of course, isn’t true, as librarians are providing digital storytimes, informational guides to COVID-19 and any other number of topics their patrons seek, book lists, technology troubleshooting, reference, and so much more. What happens off-desk in the world of libraries can often be easily done at home, while many of the on-desk work is perfectly suitable for working from home. And with such robust online social networks, the number of potential tasks for library employees to engage with while working from home is limitless—there are lists floating around, providing not just the what and the how, but also a real way for showcasing to the general public what it is library workers do.

The Special Libraries Association (SLA) has issued dire warnings about the impact of laying off information professionals during the pandemic. “Cutting library and information professionals during economic downturns has proven to have negative consequences and is increasingly short-sighted in a global marketplace that is becoming more interconnected with each passing day,” said SLA President Tara Murray, adding that now is the time information professions look to how they can be leaders when it comes to post-COVID operational efforts. “A critical step in this process is retaining and compensating staff who manage the information resources that power business, civic, and academic operations, even if such operations must be suspended temporarily.”

The executive board of the American Library Association (ALA) has issued a far less urgent statement on the matter. The statement, which came on Library Workers Day, doesn’t provide the same level of care for its members as that of SLA or any number of state library organizations. Advocates point to statements like those made by the Massachusetts Library Association and the Kansas Library Association (KLA), which put the needs and safety of the library worker above those of the library as an institution.

“The official KLA stance is ‘Close the library. Pay the staff. Do what you can with what you have’,” reads the statement from KLA’s president Robin Newell. “Close the library to the public, do not do curbside (which is inviting your patrons to leave their homes), close your drop boxes, forgive fines during this time, allow your staff to work from home, document their time and pay them for their work. Losing staff because they are not being paid will only make it harder for a library to open once this crisis is over.”

Statements like these provide solidarity to those who make the libraries what they are. It is troubling that ALA, the umbrella organization, has remained distant from the realities of those working at the ground level.

“I think some orgs have lost sight of how important it is to show this kind of support for and solidarity with members and their colleagues,” said Bignoli. “In the case of ALA, their decision to make one and only one statement, and to double down on that decision even as layoffs and furloughs are devastating our field, has cost them members for sure—myself included. It makes them seem like they’re asleep at the wheel and that is most definitely not what we need from our leaders right now.”

As of this writing, no response has been received from ALA communications, though what’s going on at ALA itself is also in question. With the cancelation of their annual conference—one of their largest sources of revenue in a given year—what happens to their own employees is up in the air.

A team of library advocates, including Bignoli, has stepped in to raise awareness of the dire reality of library layoffs. Using the social hashtags #ProtectLibraryWorkers and #LibraryLayoffs, the group has developed a crowd-sourced list of library layoffs and furloughs across the U.S. and Canada, across all types of libraries.

These advocates began their work following the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, when it became clear how dangerous it was for libraries to remain open at the start of the pandemic.

“I was originally spurred to action by the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, but after a few weeks it became clear that #ProtectLibraryWorkers and stopping or at least tracking #LibraryLayoffs was a new priority. When news articles started appearing, we realized that we needed to start tracking where these layoffs and furloughs were happening in order to see what areas are most affected and to show others what exactly is happening to library workers in real time,” said one of the advocates.

It’s not simply a list, though. It’s a plan of action meant to spur letters and advocacy on behalf of information professionals and put pressure on elected officials to speak up and put forth policies to protect them.

“[T]he furloughs and layoffs that are occurring now are symptomatic of larger trends in our fields towards greater precarity of workers and lack of funding across different types of libraries and archives: unpaid internships, term-limited positions, low pay, employee surveillance, lack of benefits, anti-union management, outsourcing of technical services, eliminating positions upon retirements, etc.,” said one of the advocates who requested to be anonymous. “I think like we are seeing elsewhere (in healthcare, housing, finance), the COVID-19 crisis is not creating new inequalities and disparities, but rather surfacing ones that have been percolating for a long time.”

By showing the layoffs and furloughs by location, the goal is for constituents to write their officials using the language provided in the document—including statements by SLA and ALA—and encourage their representatives to take action. Letters and emails are one avenue, as are mentions on social media. Templates are provided in the document.

But one thing Bignoli and other advocates have pointed out is what’s been seen in private librarian social networks for weeks: library staff are mired by fear of retaliation, job loss, and ill treatment for speaking up and advocating on behalf of themselves and colleagues.

“[A] large number of library workers are very afraid to speak openly about the conditions at their workplaces for fear of retaliation,” said Bignoli, who emphasized that employees need to put their own masks on first before jumping to help others. Likewise, managers play a crucial role in helping their staff weather this storm. “One of the best things a director can do right now is lead from a perspective of ‘whole person’ management—recognize that people are at their limits right now and don’t assign them mindless busywork or give them even more uncertainty to panic about. If staff are having days where they need to take care of family matters, mental health, whatever—just let them have those days. Stress has a deleterious effect on the immune system and we should not be contributing to that in the form of unnecessary physical reporting or rigid time management.”

Privately, library workers are turning to one another for support, encouragement, and for their brain power. With so much unknown, they’re taking a temperature check on whether what their management is doing or wants to do is safe, given what is and is not known about COVID-19.

Despite what some want to believe, libraries are not among to safest spaces to open post-restriction. The report, published in Forbes by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Health Security, suggested that libraries could be among the first institutions to reopen, to which librarians raised necessary alarm.

Days later, Johns Hopkins walked back their comments after hearing from library workers about the potential dangers.

Library workers continue to debate what is and is not possible in the post-COVID world. Without leadership from a national organization, though, they’re relying on the same resources as everyone else and trying to make sense of what is—and is not—safe. Are curbside services safe, given that the virus can live upon surfaces for a period of time? Are libraries taking personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves from healthcare workers in their scramble to reopen? And just what is a library without browsing, places to sit and congregate, the opportunity to attend vibrant programming? Will the library even have the staff to run the most basic of operations?

These are the realities librarians are grappling with, and the fact is things are going to get darker before there are any answers. Whether you’re a library worker or not, though, there are things you can do to advocate on behalf of these institutions, be they your local public library or an academic library at a college across the country from where you’re at.

For library workers, the advocates behind #ProtectLibraryWorkers suggest: Share your information! If you can safely share that you’ve been laid off or know of layoffs and furloughs, reach out. Our document is all over #LibraryTwitter on purpose. We want feedback and we want to track as much as we possibly can. Share news articles that we’ve missed. And share the document widely with some of the tweets we suggest in the document. The official hashtag is #ProtectLibraryWorkers. And if you’re in a position of seniority, please advocate for your staff. Furloughs and layoffs should be an absolute last resort. If these jobs are in the budget, please keep them there. I get too many messages, which we treat as anonymous tips in the document, saying that they know of layoffs or furloughs in a certain library. My standard response has become, “Thank you for the information, I’m so sorry if you’re one of those positions laid off.” The standard reply has become “You’re welcome, and I am.”

For library users: If you care about library funding, you care about library workers. Without us, libraries are buildings with books. If your local library has a board of trustees, contact them. An email address is usually posted on the library’s website. Show your local officials what’s happening to libraries around the country and how libraries are being adversely impacted. Advocate that they #ProtectLibraryWorkers, because libraries aren’t just buildings with books. We are community centers, quality programming for people of all ages, internet access for the millions that don’t have the internet at home, and so much more. We are the heart of our communities, schools, and universities. If you care about libraries, ask your library board of trustees and city or county council to #ProtectLibraryWorkers.

Bignoli added, “Support library workers everywhere, in your town/city, on your campus, or through efforts like Help A Library Worker Out (HALO), an effort to provide direct financial assistance to library workers who are losing their jobs or forced to take reduced hours. Join local calls for advocacy around not furloughing or laying off staff and protecting library budgets in the rocky years to come. Speak up about the importance of your library to you and your family, or other people in your area who depend on free access to information, the Internet, after school activities, company, and help. You can also join in efforts to create free universal access to broadband throughout the country, such as supporting this legislation in California.”

For those who are interested in library advocacy, Bignoli and several colleagues will be hosting a free web conference May 4 from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. EST that will address library workers’ collective resilience and resistance.

It’s through the collective power of advocates, as well as library leaders, to move forward from a place of foremost concern for people over the institution. Libraries aren’t libraries without the beating hearts of those working within them: the staff.

“Libraries have increasingly become catch-all institutions to fill voids left by other social services, and workers are not empowered and are undermined by a hollow sense of vocational awe,” said one advocate who asked to remain anonymous. “But in the case of libraries, the hope is that because those priorities are uniquely premised on the institution providing a public service, that awareness and public pressure can be particularly valuable. We know that in times of economic crisis, there will be an even greater demand on libraries, so [the emphasis on] retaining and paying workers now, libraries will be in a better position to support their communities in the future.”

In still other cases, staff who aren’t comfortable in the library are told they’re required to report and if they don’t feel okay doing so, they need to use paid time off (PTO). Libraries that depend upon the hard work of those who aren’t full time, like many institutions, don’t offer PTO or other benefits to those workers. This puts lives on the line as employees choose between their health and that of their loved ones or their job and source of income.

“Library workers do not have labor-oriented organizations fighting for improved working conditions for them; our national professional organization does not serve that role and by extension nor do our state associations,” said Callan Bignoli, Library Director at Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. “This has never been more clear than it is right now.”

Vocational awe in libraries is a consistent reality, as are the ever-present worries regarding funding. Libraries, particularly public institutions, face regular threats of cuts to their budgets, and thus strive to prove their role as essential services to their communities. The fear of job cuts is real and, as is being seen broadly throughout the U.S. and Canada, happening right before our eyes.

These cuts are likely no small part of why libraries are scrambling to cobble together reopening plans. The plans range from moderately plausible, like those which suggest COVID-19 testing for all staff (with what tests?), to downright dangerous and discriminatory (a plan from East Lansing Public Library in Michigan, sent out to a public listserv for librarians, suggests sending home anyone with a temperature of 99 or higher, a failure to understand how human bodies work—99 is an average temperature for some bodies—among other glaring issues such as not addressing whether those staff will be compensated). None of the plans address sociopolitical realities like the fear Black people have in covering their faces and the challenges lived by the economically disadvantaged—can this vulnerable group get to the library? What about access to face masks?

Given that many public libraries are funded annually and have their budget already in place for the year, the swift pace of layoffs and furloughs is especially surprising. Certainly city budgets will be impacted by lost tax revenue, among other sources, but given the vital role public libraries are playing in providing accurate information and entertainment to their communities at a time when they’re most in need of both, cutting staff now appears ill-conceived and, perhaps, too quick.

“In news articles decision-makers have given a number of different reasons for these decisions, from perceived budget cuts to not believing that library workers can work from home,” said one librarian-advocate who preferred not to be named. “And it’s not just public libraries. Academic, museum, and school libraries are seeing layoffs and furloughs too, most likely because of perceived budget cuts and strains on funding.”

Optics play a role here, too. Those making these cuts believe that library staff working from home may appear to not be working and are still being paid. This, of course, isn’t true, as librarians are providing digital storytimes, informational guides to COVID-19 and any other number of topics their patrons seek, book lists, technology troubleshooting, reference, and so much more. What happens off-desk in the world of libraries can often be easily done at home, while many of the on-desk work is perfectly suitable for working from home. And with such robust online social networks, the number of potential tasks for library employees to engage with while working from home is limitless—there are lists floating around, providing not just the what and the how, but also a real way for showcasing to the general public what it is library workers do.

The Special Libraries Association (SLA) has issued dire warnings about the impact of laying off information professionals during the pandemic. “Cutting library and information professionals during economic downturns has proven to have negative consequences and is increasingly short-sighted in a global marketplace that is becoming more interconnected with each passing day,” said SLA President Tara Murray, adding that now is the time information professions look to how they can be leaders when it comes to post-COVID operational efforts. “A critical step in this process is retaining and compensating staff who manage the information resources that power business, civic, and academic operations, even if such operations must be suspended temporarily.”

The executive board of the American Library Association (ALA) has issued a far less urgent statement on the matter. The statement, which came on Library Workers Day, doesn’t provide the same level of care for its members as that of SLA or any number of state library organizations. Advocates point to statements like those made by the Massachusetts Library Association and the Kansas Library Association (KLA), which put the needs and safety of the library worker above those of the library as an institution.

“The official KLA stance is ‘Close the library. Pay the staff. Do what you can with what you have’,” reads the statement from KLA’s president Robin Newell. “Close the library to the public, do not do curbside (which is inviting your patrons to leave their homes), close your drop boxes, forgive fines during this time, allow your staff to work from home, document their time and pay them for their work. Losing staff because they are not being paid will only make it harder for a library to open once this crisis is over.”

Statements like these provide solidarity to those who make the libraries what they are. It is troubling that ALA, the umbrella organization, has remained distant from the realities of those working at the ground level.

“I think some orgs have lost sight of how important it is to show this kind of support for and solidarity with members and their colleagues,” said Bignoli. “In the case of ALA, their decision to make one and only one statement, and to double down on that decision even as layoffs and furloughs are devastating our field, has cost them members for sure—myself included. It makes them seem like they’re asleep at the wheel and that is most definitely not what we need from our leaders right now.”

As of this writing, no response has been received from ALA communications, though what’s going on at ALA itself is also in question. With the cancelation of their annual conference—one of their largest sources of revenue in a given year—what happens to their own employees is up in the air.

A team of library advocates, including Bignoli, has stepped in to raise awareness of the dire reality of library layoffs. Using the social hashtags #ProtectLibraryWorkers and #LibraryLayoffs, the group has developed a crowd-sourced list of library layoffs and furloughs across the U.S. and Canada, across all types of libraries.

These advocates began their work following the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, when it became clear how dangerous it was for libraries to remain open at the start of the pandemic.

“I was originally spurred to action by the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, but after a few weeks it became clear that #ProtectLibraryWorkers and stopping or at least tracking #LibraryLayoffs was a new priority. When news articles started appearing, we realized that we needed to start tracking where these layoffs and furloughs were happening in order to see what areas are most affected and to show others what exactly is happening to library workers in real time,” said one of the advocates.

It’s not simply a list, though. It’s a plan of action meant to spur letters and advocacy on behalf of information professionals and put pressure on elected officials to speak up and put forth policies to protect them.

“[T]he furloughs and layoffs that are occurring now are symptomatic of larger trends in our fields towards greater precarity of workers and lack of funding across different types of libraries and archives: unpaid internships, term-limited positions, low pay, employee surveillance, lack of benefits, anti-union management, outsourcing of technical services, eliminating positions upon retirements, etc.,” said one of the advocates who requested to be anonymous. “I think like we are seeing elsewhere (in healthcare, housing, finance), the COVID-19 crisis is not creating new inequalities and disparities, but rather surfacing ones that have been percolating for a long time.”

By showing the layoffs and furloughs by location, the goal is for constituents to write their officials using the language provided in the document—including statements by SLA and ALA—and encourage their representatives to take action. Letters and emails are one avenue, as are mentions on social media. Templates are provided in the document.

But one thing Bignoli and other advocates have pointed out is what’s been seen in private librarian social networks for weeks: library staff are mired by fear of retaliation, job loss, and ill treatment for speaking up and advocating on behalf of themselves and colleagues.

“[A] large number of library workers are very afraid to speak openly about the conditions at their workplaces for fear of retaliation,” said Bignoli, who emphasized that employees need to put their own masks on first before jumping to help others. Likewise, managers play a crucial role in helping their staff weather this storm. “One of the best things a director can do right now is lead from a perspective of ‘whole person’ management—recognize that people are at their limits right now and don’t assign them mindless busywork or give them even more uncertainty to panic about. If staff are having days where they need to take care of family matters, mental health, whatever—just let them have those days. Stress has a deleterious effect on the immune system and we should not be contributing to that in the form of unnecessary physical reporting or rigid time management.”

Privately, library workers are turning to one another for support, encouragement, and for their brain power. With so much unknown, they’re taking a temperature check on whether what their management is doing or wants to do is safe, given what is and is not known about COVID-19.

Despite what some want to believe, libraries are not among to safest spaces to open post-restriction. The report, published in Forbes by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Health Security, suggested that libraries could be among the first institutions to reopen, to which librarians raised necessary alarm.

Days later, Johns Hopkins walked back their comments after hearing from library workers about the potential dangers.

Library workers continue to debate what is and is not possible in the post-COVID world. Without leadership from a national organization, though, they’re relying on the same resources as everyone else and trying to make sense of what is—and is not—safe. Are curbside services safe, given that the virus can live upon surfaces for a period of time? Are libraries taking personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves from healthcare workers in their scramble to reopen? And just what is a library without browsing, places to sit and congregate, the opportunity to attend vibrant programming? Will the library even have the staff to run the most basic of operations?

These are the realities librarians are grappling with, and the fact is things are going to get darker before there are any answers. Whether you’re a library worker or not, though, there are things you can do to advocate on behalf of these institutions, be they your local public library or an academic library at a college across the country from where you’re at.

For library workers, the advocates behind #ProtectLibraryWorkers suggest: Share your information! If you can safely share that you’ve been laid off or know of layoffs and furloughs, reach out. Our document is all over #LibraryTwitter on purpose. We want feedback and we want to track as much as we possibly can. Share news articles that we’ve missed. And share the document widely with some of the tweets we suggest in the document. The official hashtag is #ProtectLibraryWorkers. And if you’re in a position of seniority, please advocate for your staff. Furloughs and layoffs should be an absolute last resort. If these jobs are in the budget, please keep them there. I get too many messages, which we treat as anonymous tips in the document, saying that they know of layoffs or furloughs in a certain library. My standard response has become, “Thank you for the information, I’m so sorry if you’re one of those positions laid off.” The standard reply has become “You’re welcome, and I am.”

For library users: If you care about library funding, you care about library workers. Without us, libraries are buildings with books. If your local library has a board of trustees, contact them. An email address is usually posted on the library’s website. Show your local officials what’s happening to libraries around the country and how libraries are being adversely impacted. Advocate that they #ProtectLibraryWorkers, because libraries aren’t just buildings with books. We are community centers, quality programming for people of all ages, internet access for the millions that don’t have the internet at home, and so much more. We are the heart of our communities, schools, and universities. If you care about libraries, ask your library board of trustees and city or county council to #ProtectLibraryWorkers.

Bignoli added, “Support library workers everywhere, in your town/city, on your campus, or through efforts like Help A Library Worker Out (HALO), an effort to provide direct financial assistance to library workers who are losing their jobs or forced to take reduced hours. Join local calls for advocacy around not furloughing or laying off staff and protecting library budgets in the rocky years to come. Speak up about the importance of your library to you and your family, or other people in your area who depend on free access to information, the Internet, after school activities, company, and help. You can also join in efforts to create free universal access to broadband throughout the country, such as supporting this legislation in California.”

For those who are interested in library advocacy, Bignoli and several colleagues will be hosting a free web conference May 4 from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. EST that will address library workers’ collective resilience and resistance.

It’s through the collective power of advocates, as well as library leaders, to move forward from a place of foremost concern for people over the institution. Libraries aren’t libraries without the beating hearts of those working within them: the staff.

“Libraries have increasingly become catch-all institutions to fill voids left by other social services, and workers are not empowered and are undermined by a hollow sense of vocational awe,” said one advocate who asked to remain anonymous. “But in the case of libraries, the hope is that because those priorities are uniquely premised on the institution providing a public service, that awareness and public pressure can be particularly valuable. We know that in times of economic crisis, there will be an even greater demand on libraries, so [the emphasis on] retaining and paying workers now, libraries will be in a better position to support their communities in the future.”

Editor’s Note: Minutes after this piece went live, an update from ALA came through from ALA Executive Director Tracie Hall. Read in full below. “There’s good reason to be concerned. Everybody is feeling the heat impact of the pandemic, and that includes libraries. ALA is concerned for our members, the profession and the people libraries serve. Just when our libraries are needed the most, funding is decreasing. State and local governments, the primary funding sources for libraries, are making hard decisions to address deficits, and some libraries have already begun to furlough workers. City, county and state budgets are incredibly fluid during this crisis—with change happening on a daily, if not hourly, basis. “ALA advocates that library workers are paid fully during this time and continue to receive benefits such as health insurance. In municipalities where budgets are being slashed and library workers are being furloughed or laid off, ALA strongly urges the federal government to step in and provide relief for these second responders, who are getting communities through this crisis and will enable our country to get back on its feet during the recovery. Right now, a bipartisan letter is circulating in the U.S. Senate, urging additional federal funding for libraries in the next stimulus package. Anyone who supports libraries should ask their Senators to sign this letter. “ (*Note: More than 100,000 libraries nationwide report to different local jurisdictions and institutions. To date there has been no single centralized federal agency tracking how many library staff have been furloughed or laid off, making it difficult to ascertain the exact number. For this and other reasons, the American Library Association this week announced the formation of its COVID-19 Recovery Initiative which will have data gathering and analysis among its central areas of support for libraries in the weeks and months to come.)

In still other cases, staff who aren’t comfortable in the library are told they’re required to report and if they don’t feel okay doing so, they need to use paid time off (PTO). Libraries that depend upon the hard work of those who aren’t full time, like many institutions, don’t offer PTO or other benefits to those workers. This puts lives on the line as employees choose between their health and that of their loved ones or their job and source of income.

“Library workers do not have labor-oriented organizations fighting for improved working conditions for them; our national professional organization does not serve that role and by extension nor do our state associations,” said Callan Bignoli, Library Director at Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. “This has never been more clear than it is right now.”

Vocational awe in libraries is a consistent reality, as are the ever-present worries regarding funding. Libraries, particularly public institutions, face regular threats of cuts to their budgets, and thus strive to prove their role as essential services to their communities. The fear of job cuts is real and, as is being seen broadly throughout the U.S. and Canada, happening right before our eyes.

These cuts are likely no small part of why libraries are scrambling to cobble together reopening plans. The plans range from moderately plausible, like those which suggest COVID-19 testing for all staff (with what tests?), to downright dangerous and discriminatory (a plan from East Lansing Public Library in Michigan, sent out to a public listserv for librarians, suggests sending home anyone with a temperature of 99 or higher, a failure to understand how human bodies work—99 is an average temperature for some bodies—among other glaring issues such as not addressing whether those staff will be compensated). None of the plans address sociopolitical realities like the fear Black people have in covering their faces and the challenges lived by the economically disadvantaged—can this vulnerable group get to the library? What about access to face masks?

Given that many public libraries are funded annually and have their budget already in place for the year, the swift pace of layoffs and furloughs is especially surprising. Certainly city budgets will be impacted by lost tax revenue, among other sources, but given the vital role public libraries are playing in providing accurate information and entertainment to their communities at a time when they’re most in need of both, cutting staff now appears ill-conceived and, perhaps, too quick.

“In news articles decision-makers have given a number of different reasons for these decisions, from perceived budget cuts to not believing that library workers can work from home,” said one librarian-advocate who preferred not to be named. “And it’s not just public libraries. Academic, museum, and school libraries are seeing layoffs and furloughs too, most likely because of perceived budget cuts and strains on funding.”

Optics play a role here, too. Those making these cuts believe that library staff working from home may appear to not be working and are still being paid. This, of course, isn’t true, as librarians are providing digital storytimes, informational guides to COVID-19 and any other number of topics their patrons seek, book lists, technology troubleshooting, reference, and so much more. What happens off-desk in the world of libraries can often be easily done at home, while many of the on-desk work is perfectly suitable for working from home. And with such robust online social networks, the number of potential tasks for library employees to engage with while working from home is limitless—there are lists floating around, providing not just the what and the how, but also a real way for showcasing to the general public what it is library workers do.

The Special Libraries Association (SLA) has issued dire warnings about the impact of laying off information professionals during the pandemic. “Cutting library and information professionals during economic downturns has proven to have negative consequences and is increasingly short-sighted in a global marketplace that is becoming more interconnected with each passing day,” said SLA President Tara Murray, adding that now is the time information professions look to how they can be leaders when it comes to post-COVID operational efforts. “A critical step in this process is retaining and compensating staff who manage the information resources that power business, civic, and academic operations, even if such operations must be suspended temporarily.”

The executive board of the American Library Association (ALA) has issued a far less urgent statement on the matter. The statement, which came on Library Workers Day, doesn’t provide the same level of care for its members as that of SLA or any number of state library organizations. Advocates point to statements like those made by the Massachusetts Library Association and the Kansas Library Association (KLA), which put the needs and safety of the library worker above those of the library as an institution.

“The official KLA stance is ‘Close the library. Pay the staff. Do what you can with what you have’,” reads the statement from KLA’s president Robin Newell. “Close the library to the public, do not do curbside (which is inviting your patrons to leave their homes), close your drop boxes, forgive fines during this time, allow your staff to work from home, document their time and pay them for their work. Losing staff because they are not being paid will only make it harder for a library to open once this crisis is over.”

Statements like these provide solidarity to those who make the libraries what they are. It is troubling that ALA, the umbrella organization, has remained distant from the realities of those working at the ground level.

“I think some orgs have lost sight of how important it is to show this kind of support for and solidarity with members and their colleagues,” said Bignoli. “In the case of ALA, their decision to make one and only one statement, and to double down on that decision even as layoffs and furloughs are devastating our field, has cost them members for sure—myself included. It makes them seem like they’re asleep at the wheel and that is most definitely not what we need from our leaders right now.”

As of this writing, no response has been received from ALA communications, though what’s going on at ALA itself is also in question. With the cancelation of their annual conference—one of their largest sources of revenue in a given year—what happens to their own employees is up in the air.

A team of library advocates, including Bignoli, has stepped in to raise awareness of the dire reality of library layoffs. Using the social hashtags #ProtectLibraryWorkers and #LibraryLayoffs, the group has developed a crowd-sourced list of library layoffs and furloughs across the U.S. and Canada, across all types of libraries.

These advocates began their work following the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, when it became clear how dangerous it was for libraries to remain open at the start of the pandemic.

“I was originally spurred to action by the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, but after a few weeks it became clear that #ProtectLibraryWorkers and stopping or at least tracking #LibraryLayoffs was a new priority. When news articles started appearing, we realized that we needed to start tracking where these layoffs and furloughs were happening in order to see what areas are most affected and to show others what exactly is happening to library workers in real time,” said one of the advocates.

It’s not simply a list, though. It’s a plan of action meant to spur letters and advocacy on behalf of information professionals and put pressure on elected officials to speak up and put forth policies to protect them.

“[T]he furloughs and layoffs that are occurring now are symptomatic of larger trends in our fields towards greater precarity of workers and lack of funding across different types of libraries and archives: unpaid internships, term-limited positions, low pay, employee surveillance, lack of benefits, anti-union management, outsourcing of technical services, eliminating positions upon retirements, etc.,” said one of the advocates who requested to be anonymous. “I think like we are seeing elsewhere (in healthcare, housing, finance), the COVID-19 crisis is not creating new inequalities and disparities, but rather surfacing ones that have been percolating for a long time.”

By showing the layoffs and furloughs by location, the goal is for constituents to write their officials using the language provided in the document—including statements by SLA and ALA—and encourage their representatives to take action. Letters and emails are one avenue, as are mentions on social media. Templates are provided in the document.

But one thing Bignoli and other advocates have pointed out is what’s been seen in private librarian social networks for weeks: library staff are mired by fear of retaliation, job loss, and ill treatment for speaking up and advocating on behalf of themselves and colleagues.

“[A] large number of library workers are very afraid to speak openly about the conditions at their workplaces for fear of retaliation,” said Bignoli, who emphasized that employees need to put their own masks on first before jumping to help others. Likewise, managers play a crucial role in helping their staff weather this storm. “One of the best things a director can do right now is lead from a perspective of ‘whole person’ management—recognize that people are at their limits right now and don’t assign them mindless busywork or give them even more uncertainty to panic about. If staff are having days where they need to take care of family matters, mental health, whatever—just let them have those days. Stress has a deleterious effect on the immune system and we should not be contributing to that in the form of unnecessary physical reporting or rigid time management.”

Privately, library workers are turning to one another for support, encouragement, and for their brain power. With so much unknown, they’re taking a temperature check on whether what their management is doing or wants to do is safe, given what is and is not known about COVID-19.

Despite what some want to believe, libraries are not among to safest spaces to open post-restriction. The report, published in Forbes by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Health Security, suggested that libraries could be among the first institutions to reopen, to which librarians raised necessary alarm.

Days later, Johns Hopkins walked back their comments after hearing from library workers about the potential dangers.

Library workers continue to debate what is and is not possible in the post-COVID world. Without leadership from a national organization, though, they’re relying on the same resources as everyone else and trying to make sense of what is—and is not—safe. Are curbside services safe, given that the virus can live upon surfaces for a period of time? Are libraries taking personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves from healthcare workers in their scramble to reopen? And just what is a library without browsing, places to sit and congregate, the opportunity to attend vibrant programming? Will the library even have the staff to run the most basic of operations?

These are the realities librarians are grappling with, and the fact is things are going to get darker before there are any answers. Whether you’re a library worker or not, though, there are things you can do to advocate on behalf of these institutions, be they your local public library or an academic library at a college across the country from where you’re at.

For library workers, the advocates behind #ProtectLibraryWorkers suggest: Share your information! If you can safely share that you’ve been laid off or know of layoffs and furloughs, reach out. Our document is all over #LibraryTwitter on purpose. We want feedback and we want to track as much as we possibly can. Share news articles that we’ve missed. And share the document widely with some of the tweets we suggest in the document. The official hashtag is #ProtectLibraryWorkers. And if you’re in a position of seniority, please advocate for your staff. Furloughs and layoffs should be an absolute last resort. If these jobs are in the budget, please keep them there. I get too many messages, which we treat as anonymous tips in the document, saying that they know of layoffs or furloughs in a certain library. My standard response has become, “Thank you for the information, I’m so sorry if you’re one of those positions laid off.” The standard reply has become “You’re welcome, and I am.”

For library users: If you care about library funding, you care about library workers. Without us, libraries are buildings with books. If your local library has a board of trustees, contact them. An email address is usually posted on the library’s website. Show your local officials what’s happening to libraries around the country and how libraries are being adversely impacted. Advocate that they #ProtectLibraryWorkers, because libraries aren’t just buildings with books. We are community centers, quality programming for people of all ages, internet access for the millions that don’t have the internet at home, and so much more. We are the heart of our communities, schools, and universities. If you care about libraries, ask your library board of trustees and city or county council to #ProtectLibraryWorkers.

Bignoli added, “Support library workers everywhere, in your town/city, on your campus, or through efforts like Help A Library Worker Out (HALO), an effort to provide direct financial assistance to library workers who are losing their jobs or forced to take reduced hours. Join local calls for advocacy around not furloughing or laying off staff and protecting library budgets in the rocky years to come. Speak up about the importance of your library to you and your family, or other people in your area who depend on free access to information, the Internet, after school activities, company, and help. You can also join in efforts to create free universal access to broadband throughout the country, such as supporting this legislation in California.”

For those who are interested in library advocacy, Bignoli and several colleagues will be hosting a free web conference May 4 from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. EST that will address library workers’ collective resilience and resistance.

It’s through the collective power of advocates, as well as library leaders, to move forward from a place of foremost concern for people over the institution. Libraries aren’t libraries without the beating hearts of those working within them: the staff.

“Libraries have increasingly become catch-all institutions to fill voids left by other social services, and workers are not empowered and are undermined by a hollow sense of vocational awe,” said one advocate who asked to remain anonymous. “But in the case of libraries, the hope is that because those priorities are uniquely premised on the institution providing a public service, that awareness and public pressure can be particularly valuable. We know that in times of economic crisis, there will be an even greater demand on libraries, so [the emphasis on] retaining and paying workers now, libraries will be in a better position to support their communities in the future.”

In still other cases, staff who aren’t comfortable in the library are told they’re required to report and if they don’t feel okay doing so, they need to use paid time off (PTO). Libraries that depend upon the hard work of those who aren’t full time, like many institutions, don’t offer PTO or other benefits to those workers. This puts lives on the line as employees choose between their health and that of their loved ones or their job and source of income.

“Library workers do not have labor-oriented organizations fighting for improved working conditions for them; our national professional organization does not serve that role and by extension nor do our state associations,” said Callan Bignoli, Library Director at Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. “This has never been more clear than it is right now.”

Vocational awe in libraries is a consistent reality, as are the ever-present worries regarding funding. Libraries, particularly public institutions, face regular threats of cuts to their budgets, and thus strive to prove their role as essential services to their communities. The fear of job cuts is real and, as is being seen broadly throughout the U.S. and Canada, happening right before our eyes.

These cuts are likely no small part of why libraries are scrambling to cobble together reopening plans. The plans range from moderately plausible, like those which suggest COVID-19 testing for all staff (with what tests?), to downright dangerous and discriminatory (a plan from East Lansing Public Library in Michigan, sent out to a public listserv for librarians, suggests sending home anyone with a temperature of 99 or higher, a failure to understand how human bodies work—99 is an average temperature for some bodies—among other glaring issues such as not addressing whether those staff will be compensated). None of the plans address sociopolitical realities like the fear Black people have in covering their faces and the challenges lived by the economically disadvantaged—can this vulnerable group get to the library? What about access to face masks?

Given that many public libraries are funded annually and have their budget already in place for the year, the swift pace of layoffs and furloughs is especially surprising. Certainly city budgets will be impacted by lost tax revenue, among other sources, but given the vital role public libraries are playing in providing accurate information and entertainment to their communities at a time when they’re most in need of both, cutting staff now appears ill-conceived and, perhaps, too quick.

“In news articles decision-makers have given a number of different reasons for these decisions, from perceived budget cuts to not believing that library workers can work from home,” said one librarian-advocate who preferred not to be named. “And it’s not just public libraries. Academic, museum, and school libraries are seeing layoffs and furloughs too, most likely because of perceived budget cuts and strains on funding.”

Optics play a role here, too. Those making these cuts believe that library staff working from home may appear to not be working and are still being paid. This, of course, isn’t true, as librarians are providing digital storytimes, informational guides to COVID-19 and any other number of topics their patrons seek, book lists, technology troubleshooting, reference, and so much more. What happens off-desk in the world of libraries can often be easily done at home, while many of the on-desk work is perfectly suitable for working from home. And with such robust online social networks, the number of potential tasks for library employees to engage with while working from home is limitless—there are lists floating around, providing not just the what and the how, but also a real way for showcasing to the general public what it is library workers do.

The Special Libraries Association (SLA) has issued dire warnings about the impact of laying off information professionals during the pandemic. “Cutting library and information professionals during economic downturns has proven to have negative consequences and is increasingly short-sighted in a global marketplace that is becoming more interconnected with each passing day,” said SLA President Tara Murray, adding that now is the time information professions look to how they can be leaders when it comes to post-COVID operational efforts. “A critical step in this process is retaining and compensating staff who manage the information resources that power business, civic, and academic operations, even if such operations must be suspended temporarily.”

The executive board of the American Library Association (ALA) has issued a far less urgent statement on the matter. The statement, which came on Library Workers Day, doesn’t provide the same level of care for its members as that of SLA or any number of state library organizations. Advocates point to statements like those made by the Massachusetts Library Association and the Kansas Library Association (KLA), which put the needs and safety of the library worker above those of the library as an institution.

“The official KLA stance is ‘Close the library. Pay the staff. Do what you can with what you have’,” reads the statement from KLA’s president Robin Newell. “Close the library to the public, do not do curbside (which is inviting your patrons to leave their homes), close your drop boxes, forgive fines during this time, allow your staff to work from home, document their time and pay them for their work. Losing staff because they are not being paid will only make it harder for a library to open once this crisis is over.”

Statements like these provide solidarity to those who make the libraries what they are. It is troubling that ALA, the umbrella organization, has remained distant from the realities of those working at the ground level.

“I think some orgs have lost sight of how important it is to show this kind of support for and solidarity with members and their colleagues,” said Bignoli. “In the case of ALA, their decision to make one and only one statement, and to double down on that decision even as layoffs and furloughs are devastating our field, has cost them members for sure—myself included. It makes them seem like they’re asleep at the wheel and that is most definitely not what we need from our leaders right now.”

As of this writing, no response has been received from ALA communications, though what’s going on at ALA itself is also in question. With the cancelation of their annual conference—one of their largest sources of revenue in a given year—what happens to their own employees is up in the air.

A team of library advocates, including Bignoli, has stepped in to raise awareness of the dire reality of library layoffs. Using the social hashtags #ProtectLibraryWorkers and #LibraryLayoffs, the group has developed a crowd-sourced list of library layoffs and furloughs across the U.S. and Canada, across all types of libraries.

These advocates began their work following the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, when it became clear how dangerous it was for libraries to remain open at the start of the pandemic.

“I was originally spurred to action by the #CloseTheLibraries campaign, but after a few weeks it became clear that #ProtectLibraryWorkers and stopping or at least tracking #LibraryLayoffs was a new priority. When news articles started appearing, we realized that we needed to start tracking where these layoffs and furloughs were happening in order to see what areas are most affected and to show others what exactly is happening to library workers in real time,” said one of the advocates.

It’s not simply a list, though. It’s a plan of action meant to spur letters and advocacy on behalf of information professionals and put pressure on elected officials to speak up and put forth policies to protect them.

“[T]he furloughs and layoffs that are occurring now are symptomatic of larger trends in our fields towards greater precarity of workers and lack of funding across different types of libraries and archives: unpaid internships, term-limited positions, low pay, employee surveillance, lack of benefits, anti-union management, outsourcing of technical services, eliminating positions upon retirements, etc.,” said one of the advocates who requested to be anonymous. “I think like we are seeing elsewhere (in healthcare, housing, finance), the COVID-19 crisis is not creating new inequalities and disparities, but rather surfacing ones that have been percolating for a long time.”

By showing the layoffs and furloughs by location, the goal is for constituents to write their officials using the language provided in the document—including statements by SLA and ALA—and encourage their representatives to take action. Letters and emails are one avenue, as are mentions on social media. Templates are provided in the document.

But one thing Bignoli and other advocates have pointed out is what’s been seen in private librarian social networks for weeks: library staff are mired by fear of retaliation, job loss, and ill treatment for speaking up and advocating on behalf of themselves and colleagues.

“[A] large number of library workers are very afraid to speak openly about the conditions at their workplaces for fear of retaliation,” said Bignoli, who emphasized that employees need to put their own masks on first before jumping to help others. Likewise, managers play a crucial role in helping their staff weather this storm. “One of the best things a director can do right now is lead from a perspective of ‘whole person’ management—recognize that people are at their limits right now and don’t assign them mindless busywork or give them even more uncertainty to panic about. If staff are having days where they need to take care of family matters, mental health, whatever—just let them have those days. Stress has a deleterious effect on the immune system and we should not be contributing to that in the form of unnecessary physical reporting or rigid time management.”

Privately, library workers are turning to one another for support, encouragement, and for their brain power. With so much unknown, they’re taking a temperature check on whether what their management is doing or wants to do is safe, given what is and is not known about COVID-19.

Despite what some want to believe, libraries are not among to safest spaces to open post-restriction. The report, published in Forbes by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Health Security, suggested that libraries could be among the first institutions to reopen, to which librarians raised necessary alarm.

Days later, Johns Hopkins walked back their comments after hearing from library workers about the potential dangers.

Library workers continue to debate what is and is not possible in the post-COVID world. Without leadership from a national organization, though, they’re relying on the same resources as everyone else and trying to make sense of what is—and is not—safe. Are curbside services safe, given that the virus can live upon surfaces for a period of time? Are libraries taking personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves from healthcare workers in their scramble to reopen? And just what is a library without browsing, places to sit and congregate, the opportunity to attend vibrant programming? Will the library even have the staff to run the most basic of operations?

These are the realities librarians are grappling with, and the fact is things are going to get darker before there are any answers. Whether you’re a library worker or not, though, there are things you can do to advocate on behalf of these institutions, be they your local public library or an academic library at a college across the country from where you’re at.

For library workers, the advocates behind #ProtectLibraryWorkers suggest: Share your information! If you can safely share that you’ve been laid off or know of layoffs and furloughs, reach out. Our document is all over #LibraryTwitter on purpose. We want feedback and we want to track as much as we possibly can. Share news articles that we’ve missed. And share the document widely with some of the tweets we suggest in the document. The official hashtag is #ProtectLibraryWorkers. And if you’re in a position of seniority, please advocate for your staff. Furloughs and layoffs should be an absolute last resort. If these jobs are in the budget, please keep them there. I get too many messages, which we treat as anonymous tips in the document, saying that they know of layoffs or furloughs in a certain library. My standard response has become, “Thank you for the information, I’m so sorry if you’re one of those positions laid off.” The standard reply has become “You’re welcome, and I am.”

For library users: If you care about library funding, you care about library workers. Without us, libraries are buildings with books. If your local library has a board of trustees, contact them. An email address is usually posted on the library’s website. Show your local officials what’s happening to libraries around the country and how libraries are being adversely impacted. Advocate that they #ProtectLibraryWorkers, because libraries aren’t just buildings with books. We are community centers, quality programming for people of all ages, internet access for the millions that don’t have the internet at home, and so much more. We are the heart of our communities, schools, and universities. If you care about libraries, ask your library board of trustees and city or county council to #ProtectLibraryWorkers.

Bignoli added, “Support library workers everywhere, in your town/city, on your campus, or through efforts like Help A Library Worker Out (HALO), an effort to provide direct financial assistance to library workers who are losing their jobs or forced to take reduced hours. Join local calls for advocacy around not furloughing or laying off staff and protecting library budgets in the rocky years to come. Speak up about the importance of your library to you and your family, or other people in your area who depend on free access to information, the Internet, after school activities, company, and help. You can also join in efforts to create free universal access to broadband throughout the country, such as supporting this legislation in California.”

For those who are interested in library advocacy, Bignoli and several colleagues will be hosting a free web conference May 4 from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. EST that will address library workers’ collective resilience and resistance.

It’s through the collective power of advocates, as well as library leaders, to move forward from a place of foremost concern for people over the institution. Libraries aren’t libraries without the beating hearts of those working within them: the staff.

“Libraries have increasingly become catch-all institutions to fill voids left by other social services, and workers are not empowered and are undermined by a hollow sense of vocational awe,” said one advocate who asked to remain anonymous. “But in the case of libraries, the hope is that because those priorities are uniquely premised on the institution providing a public service, that awareness and public pressure can be particularly valuable. We know that in times of economic crisis, there will be an even greater demand on libraries, so [the emphasis on] retaining and paying workers now, libraries will be in a better position to support their communities in the future.”

Editor’s Note: Minutes after this piece went live, an update from ALA came through from ALA Executive Director Tracie Hall. Read in full below. “There’s good reason to be concerned. Everybody is feeling the heat impact of the pandemic, and that includes libraries. ALA is concerned for our members, the profession and the people libraries serve. Just when our libraries are needed the most, funding is decreasing. State and local governments, the primary funding sources for libraries, are making hard decisions to address deficits, and some libraries have already begun to furlough workers. City, county and state budgets are incredibly fluid during this crisis—with change happening on a daily, if not hourly, basis. “ALA advocates that library workers are paid fully during this time and continue to receive benefits such as health insurance. In municipalities where budgets are being slashed and library workers are being furloughed or laid off, ALA strongly urges the federal government to step in and provide relief for these second responders, who are getting communities through this crisis and will enable our country to get back on its feet during the recovery. Right now, a bipartisan letter is circulating in the U.S. Senate, urging additional federal funding for libraries in the next stimulus package. Anyone who supports libraries should ask their Senators to sign this letter. “ (*Note: More than 100,000 libraries nationwide report to different local jurisdictions and institutions. To date there has been no single centralized federal agency tracking how many library staff have been furloughed or laid off, making it difficult to ascertain the exact number. For this and other reasons, the American Library Association this week announced the formation of its COVID-19 Recovery Initiative which will have data gathering and analysis among its central areas of support for libraries in the weeks and months to come.)