This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Elizabeth I Coronation Portrait

Elizabeth with Anne Boleyn’s “A” necklace

At various times of her youth, she was a princess, declared a bastard and removed from the line of succession, reinstated, a political prisoner held in the Tower, and survived a sexual scandal that led, in part, to the execution of Sir Thomas Seymour. All without her mother there to comfort her.

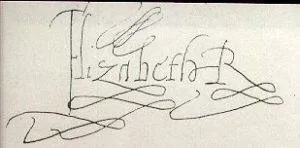

Elizabeth’s signature