Pura Belpré, the First Puerto Rican Librarian in NYC (And My Library Hero)

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

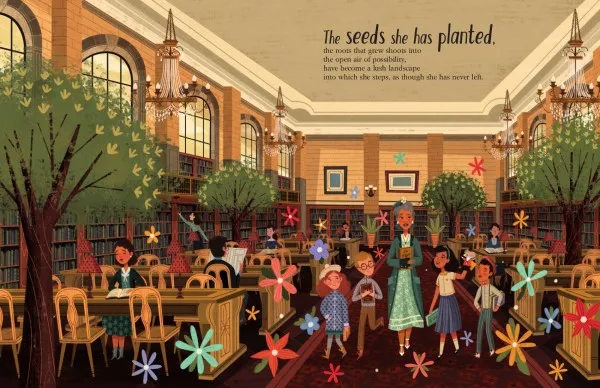

I’ve been a library professional for seven years now, primarily working in children’s services for the last four. However, until I read the picture book Planting Stories: The Life of Librarian and Storyteller Pura Belpré, I knew nothing about her existence or her achievements in librarianship.

I read about her last year and, since September, I’ve been working on my library Masters. Our prof gave us a list of historical library figures to create presentations about, and I immediately thought of Belpré. She wasn’t listed, and I was disappointed. She was an iconic, innovative librarian who altered children’s librarianship for the better and was inspirational enough to have an American Library Association award named after her (honoring children’s books by Latino writers and illustrators).

Pura Belpré was the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City. Once upon a time, long before she roamed the stacks of the New York City Public Library, she grew up in Cidra, Puerto Rico. Even as a child, she loved sharing stories – many had been first told to her by her abuela. In a 1992 profile published in The Library Quarterly, Belpré was quoted as saying: “I grew up in a home of storytellers…during school recess some of us would gather under the shade of the tamarind tree, and then we would take turns telling stories”. That affinity for stories would take her far from the tamarind trees and eventually to the streets of 1920s New York City.

Eventually, she was hired by Ernestine Rose, librarian of the 135th Street branch (now named Countee Cullen). Rose had noticed that a bodego and a barberia moved into the area around the library; realizing that there was a burgeoning community, she wanted a bilingual library assistant who would strengthen the bond between the library and its growing Spanish-speaking patron base. Belpré, who spoke Spanish, English, and French, was hired for the position.

Furthermore, she wanted to share with the children the same stories that she’d been told as a child, but was disappointed to discover that the library’s children’s collection lacked Puerto Rican folktales. Her goal became to ensure that the children didn’t lose their cultural heritage. As Lucia González writes in the intro to the book The Storyteller’s Candle, “Through her work, her stories, and her books, Pura Belpré brought the warmth and beauty of Puerto Rico to the children of El Barrio.” González tells the story of Belpré’s contributions by focusing on the experiences of these new immigrants, whose lack of English initially made them struggle to feel welcome at the libraries of New York.

Pura Belpré was the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City. Once upon a time, long before she roamed the stacks of the New York City Public Library, she grew up in Cidra, Puerto Rico. Even as a child, she loved sharing stories – many had been first told to her by her abuela. In a 1992 profile published in The Library Quarterly, Belpré was quoted as saying: “I grew up in a home of storytellers…during school recess some of us would gather under the shade of the tamarind tree, and then we would take turns telling stories”. That affinity for stories would take her far from the tamarind trees and eventually to the streets of 1920s New York City.

Eventually, she was hired by Ernestine Rose, librarian of the 135th Street branch (now named Countee Cullen). Rose had noticed that a bodego and a barberia moved into the area around the library; realizing that there was a burgeoning community, she wanted a bilingual library assistant who would strengthen the bond between the library and its growing Spanish-speaking patron base. Belpré, who spoke Spanish, English, and French, was hired for the position.

Furthermore, she wanted to share with the children the same stories that she’d been told as a child, but was disappointed to discover that the library’s children’s collection lacked Puerto Rican folktales. Her goal became to ensure that the children didn’t lose their cultural heritage. As Lucia González writes in the intro to the book The Storyteller’s Candle, “Through her work, her stories, and her books, Pura Belpré brought the warmth and beauty of Puerto Rico to the children of El Barrio.” González tells the story of Belpré’s contributions by focusing on the experiences of these new immigrants, whose lack of English initially made them struggle to feel welcome at the libraries of New York.

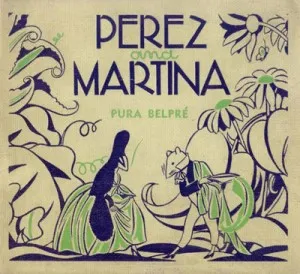

In 1925, Belpré enrolled in NYPL’s Library School; it was there that she attended a storytelling course that led to her eventual book Pérez and Martina, a romantic tragedy between a cockroach and a mouse. (Can there truly be any other kind, though?) The course’s teacher, Mary Gould Davis, gave Belpré permission to tell her own tales at storytime — a huge deal, as librarians generally only read stories from published books. Another nuance of her storytimes was that she made them cozy with a lit candle at her side, which the children would make wishes on before blowing out.

She moved a few times before settling at Harlem’s 115th Street branch, where the community was predominantly Puerto Rican, and was the first to host bilingual storytimes. She’d even make her own puppets and incorporate them — which I think shows an iconic level of creative commitment to her programming! Additionally, she organized a significant cultural event at her branch, a celebration for an important Latin American holiday called El Dia De Reyes (The Feast of the Three Kings). Incorporating dancing, music, and stories, the event fostered a strong connection between the library and the Puerto Rican community. No longer was she just a nameless librarian to them, she was a member of their community whom they knew and understood. In fact, until the end of the 1930s, the 115th Street branch was the go-to branch for Spanish books, lectures and events.

In 1925, Belpré enrolled in NYPL’s Library School; it was there that she attended a storytelling course that led to her eventual book Pérez and Martina, a romantic tragedy between a cockroach and a mouse. (Can there truly be any other kind, though?) The course’s teacher, Mary Gould Davis, gave Belpré permission to tell her own tales at storytime — a huge deal, as librarians generally only read stories from published books. Another nuance of her storytimes was that she made them cozy with a lit candle at her side, which the children would make wishes on before blowing out.

She moved a few times before settling at Harlem’s 115th Street branch, where the community was predominantly Puerto Rican, and was the first to host bilingual storytimes. She’d even make her own puppets and incorporate them — which I think shows an iconic level of creative commitment to her programming! Additionally, she organized a significant cultural event at her branch, a celebration for an important Latin American holiday called El Dia De Reyes (The Feast of the Three Kings). Incorporating dancing, music, and stories, the event fostered a strong connection between the library and the Puerto Rican community. No longer was she just a nameless librarian to them, she was a member of their community whom they knew and understood. In fact, until the end of the 1930s, the 115th Street branch was the go-to branch for Spanish books, lectures and events.

In 1932, the first first book of Puerto Rican folktales to be published in the U.S. was Pérez and Martina: A Portorican Folk Tale. The writing of other members of the community would follow because and she went on to publish other children’s stories: Rainbow-Colored Horse, The Tiger and the Rabbit and Other Tales, and many others. According to a 1980 School Library Journal article, Belpré retired after 47 staggering years at the NYPL and she was celebrated with a full week of events in her honor.

There’s a great, short listen about Belpré’s continuing legacy from NPR’s All Things Considered. Reporter Neda Ulaby points out despite the existence of the Pura Belpré Award, there is still a huge gap in the children’s publishing market for books by Latinx authors. Though the episode aired in 2016, stats from 2018 show that diversity still needs a lot of improvement. If you are looking to diversify your children’s lit to include more Latinx creators, I’d suggest starting with some of the Belpré award winners and then moving on to these titles.

To read more about her, you can pick up Lisa Sánchez González’s The Stories I Read to the Children, which contains both Belpré’s writing and biographical information about her life. To see photographs and listen to interviews, visit the site for Centro, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. If you have access (via your local library perhaps), read The Library Quarterly’s “Pura Teresa Belpré, Storyteller and Pioneer Puerto Rican Librarian” by Julio L. Hernández-Delgado. It was in that article that I found a lot of the history for this piece; once you start reading about this fascinating woman, I think that she’ll become a library hero to you too.

In 1932, the first first book of Puerto Rican folktales to be published in the U.S. was Pérez and Martina: A Portorican Folk Tale. The writing of other members of the community would follow because and she went on to publish other children’s stories: Rainbow-Colored Horse, The Tiger and the Rabbit and Other Tales, and many others. According to a 1980 School Library Journal article, Belpré retired after 47 staggering years at the NYPL and she was celebrated with a full week of events in her honor.

There’s a great, short listen about Belpré’s continuing legacy from NPR’s All Things Considered. Reporter Neda Ulaby points out despite the existence of the Pura Belpré Award, there is still a huge gap in the children’s publishing market for books by Latinx authors. Though the episode aired in 2016, stats from 2018 show that diversity still needs a lot of improvement. If you are looking to diversify your children’s lit to include more Latinx creators, I’d suggest starting with some of the Belpré award winners and then moving on to these titles.

To read more about her, you can pick up Lisa Sánchez González’s The Stories I Read to the Children, which contains both Belpré’s writing and biographical information about her life. To see photographs and listen to interviews, visit the site for Centro, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. If you have access (via your local library perhaps), read The Library Quarterly’s “Pura Teresa Belpré, Storyteller and Pioneer Puerto Rican Librarian” by Julio L. Hernández-Delgado. It was in that article that I found a lot of the history for this piece; once you start reading about this fascinating woman, I think that she’ll become a library hero to you too.

Pura Belpré was the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City. Once upon a time, long before she roamed the stacks of the New York City Public Library, she grew up in Cidra, Puerto Rico. Even as a child, she loved sharing stories – many had been first told to her by her abuela. In a 1992 profile published in The Library Quarterly, Belpré was quoted as saying: “I grew up in a home of storytellers…during school recess some of us would gather under the shade of the tamarind tree, and then we would take turns telling stories”. That affinity for stories would take her far from the tamarind trees and eventually to the streets of 1920s New York City.

Eventually, she was hired by Ernestine Rose, librarian of the 135th Street branch (now named Countee Cullen). Rose had noticed that a bodego and a barberia moved into the area around the library; realizing that there was a burgeoning community, she wanted a bilingual library assistant who would strengthen the bond between the library and its growing Spanish-speaking patron base. Belpré, who spoke Spanish, English, and French, was hired for the position.

Furthermore, she wanted to share with the children the same stories that she’d been told as a child, but was disappointed to discover that the library’s children’s collection lacked Puerto Rican folktales. Her goal became to ensure that the children didn’t lose their cultural heritage. As Lucia González writes in the intro to the book The Storyteller’s Candle, “Through her work, her stories, and her books, Pura Belpré brought the warmth and beauty of Puerto Rico to the children of El Barrio.” González tells the story of Belpré’s contributions by focusing on the experiences of these new immigrants, whose lack of English initially made them struggle to feel welcome at the libraries of New York.

Pura Belpré was the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City. Once upon a time, long before she roamed the stacks of the New York City Public Library, she grew up in Cidra, Puerto Rico. Even as a child, she loved sharing stories – many had been first told to her by her abuela. In a 1992 profile published in The Library Quarterly, Belpré was quoted as saying: “I grew up in a home of storytellers…during school recess some of us would gather under the shade of the tamarind tree, and then we would take turns telling stories”. That affinity for stories would take her far from the tamarind trees and eventually to the streets of 1920s New York City.

Eventually, she was hired by Ernestine Rose, librarian of the 135th Street branch (now named Countee Cullen). Rose had noticed that a bodego and a barberia moved into the area around the library; realizing that there was a burgeoning community, she wanted a bilingual library assistant who would strengthen the bond between the library and its growing Spanish-speaking patron base. Belpré, who spoke Spanish, English, and French, was hired for the position.

Furthermore, she wanted to share with the children the same stories that she’d been told as a child, but was disappointed to discover that the library’s children’s collection lacked Puerto Rican folktales. Her goal became to ensure that the children didn’t lose their cultural heritage. As Lucia González writes in the intro to the book The Storyteller’s Candle, “Through her work, her stories, and her books, Pura Belpré brought the warmth and beauty of Puerto Rico to the children of El Barrio.” González tells the story of Belpré’s contributions by focusing on the experiences of these new immigrants, whose lack of English initially made them struggle to feel welcome at the libraries of New York.

In 1925, Belpré enrolled in NYPL’s Library School; it was there that she attended a storytelling course that led to her eventual book Pérez and Martina, a romantic tragedy between a cockroach and a mouse. (Can there truly be any other kind, though?) The course’s teacher, Mary Gould Davis, gave Belpré permission to tell her own tales at storytime — a huge deal, as librarians generally only read stories from published books. Another nuance of her storytimes was that she made them cozy with a lit candle at her side, which the children would make wishes on before blowing out.

She moved a few times before settling at Harlem’s 115th Street branch, where the community was predominantly Puerto Rican, and was the first to host bilingual storytimes. She’d even make her own puppets and incorporate them — which I think shows an iconic level of creative commitment to her programming! Additionally, she organized a significant cultural event at her branch, a celebration for an important Latin American holiday called El Dia De Reyes (The Feast of the Three Kings). Incorporating dancing, music, and stories, the event fostered a strong connection between the library and the Puerto Rican community. No longer was she just a nameless librarian to them, she was a member of their community whom they knew and understood. In fact, until the end of the 1930s, the 115th Street branch was the go-to branch for Spanish books, lectures and events.

In 1925, Belpré enrolled in NYPL’s Library School; it was there that she attended a storytelling course that led to her eventual book Pérez and Martina, a romantic tragedy between a cockroach and a mouse. (Can there truly be any other kind, though?) The course’s teacher, Mary Gould Davis, gave Belpré permission to tell her own tales at storytime — a huge deal, as librarians generally only read stories from published books. Another nuance of her storytimes was that she made them cozy with a lit candle at her side, which the children would make wishes on before blowing out.

She moved a few times before settling at Harlem’s 115th Street branch, where the community was predominantly Puerto Rican, and was the first to host bilingual storytimes. She’d even make her own puppets and incorporate them — which I think shows an iconic level of creative commitment to her programming! Additionally, she organized a significant cultural event at her branch, a celebration for an important Latin American holiday called El Dia De Reyes (The Feast of the Three Kings). Incorporating dancing, music, and stories, the event fostered a strong connection between the library and the Puerto Rican community. No longer was she just a nameless librarian to them, she was a member of their community whom they knew and understood. In fact, until the end of the 1930s, the 115th Street branch was the go-to branch for Spanish books, lectures and events.

In 1932, the first first book of Puerto Rican folktales to be published in the U.S. was Pérez and Martina: A Portorican Folk Tale. The writing of other members of the community would follow because and she went on to publish other children’s stories: Rainbow-Colored Horse, The Tiger and the Rabbit and Other Tales, and many others. According to a 1980 School Library Journal article, Belpré retired after 47 staggering years at the NYPL and she was celebrated with a full week of events in her honor.

There’s a great, short listen about Belpré’s continuing legacy from NPR’s All Things Considered. Reporter Neda Ulaby points out despite the existence of the Pura Belpré Award, there is still a huge gap in the children’s publishing market for books by Latinx authors. Though the episode aired in 2016, stats from 2018 show that diversity still needs a lot of improvement. If you are looking to diversify your children’s lit to include more Latinx creators, I’d suggest starting with some of the Belpré award winners and then moving on to these titles.

To read more about her, you can pick up Lisa Sánchez González’s The Stories I Read to the Children, which contains both Belpré’s writing and biographical information about her life. To see photographs and listen to interviews, visit the site for Centro, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. If you have access (via your local library perhaps), read The Library Quarterly’s “Pura Teresa Belpré, Storyteller and Pioneer Puerto Rican Librarian” by Julio L. Hernández-Delgado. It was in that article that I found a lot of the history for this piece; once you start reading about this fascinating woman, I think that she’ll become a library hero to you too.

In 1932, the first first book of Puerto Rican folktales to be published in the U.S. was Pérez and Martina: A Portorican Folk Tale. The writing of other members of the community would follow because and she went on to publish other children’s stories: Rainbow-Colored Horse, The Tiger and the Rabbit and Other Tales, and many others. According to a 1980 School Library Journal article, Belpré retired after 47 staggering years at the NYPL and she was celebrated with a full week of events in her honor.

There’s a great, short listen about Belpré’s continuing legacy from NPR’s All Things Considered. Reporter Neda Ulaby points out despite the existence of the Pura Belpré Award, there is still a huge gap in the children’s publishing market for books by Latinx authors. Though the episode aired in 2016, stats from 2018 show that diversity still needs a lot of improvement. If you are looking to diversify your children’s lit to include more Latinx creators, I’d suggest starting with some of the Belpré award winners and then moving on to these titles.

To read more about her, you can pick up Lisa Sánchez González’s The Stories I Read to the Children, which contains both Belpré’s writing and biographical information about her life. To see photographs and listen to interviews, visit the site for Centro, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. If you have access (via your local library perhaps), read The Library Quarterly’s “Pura Teresa Belpré, Storyteller and Pioneer Puerto Rican Librarian” by Julio L. Hernández-Delgado. It was in that article that I found a lot of the history for this piece; once you start reading about this fascinating woman, I think that she’ll become a library hero to you too.