Why NIMONA Is Important to Me

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

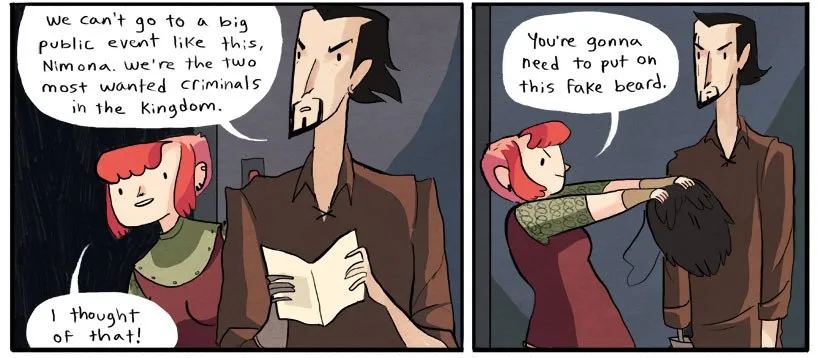

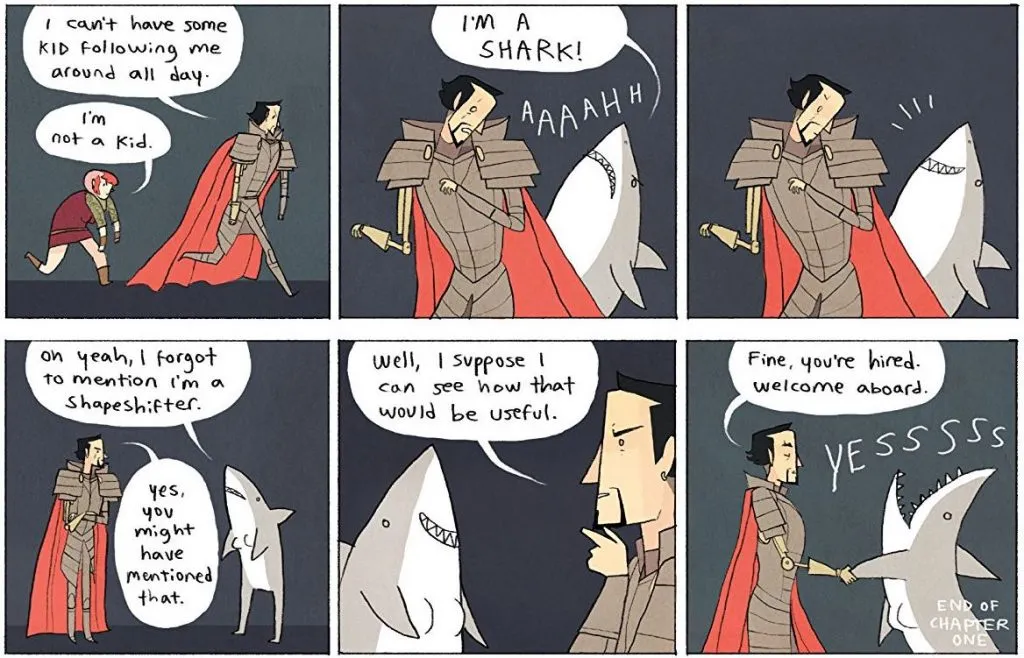

Although there’s a growing number of graphic novels written or children and young adults, it’s not every day that my love of children’s literature overlaps with my love of webcomics. In fact, I’m pretty sure that in my entire academic experience it’s happened only once—with Noelle Stevenson’s hilarious and subversive “monk punk” webcomic Nimona. I fell in love with Nimona for its complicated characters, trope-savvy humor, and quirky art, all of which come together in a fantastic story that I can (and do) recommend to everyone. But Nimona remains particularly special to me for another reason entirely: the unusual way it came to be what it is today, shapeshifting from a free, independent webcomic into a published, award-winning graphic novel.

I first started reading Nimona back in late 2013, when it was about half finished and beginning to gather a noticeably large and adoring fandom online. At the same time, in my other life as a grad student with no time for reading silly things on the internet, I was learning about the children’s literature publishing industry. Manuscripts, agents, editors, imprints, print runs, age groups, rewrites, distribution, marketing. The pseudo-myth of royalties. The near-impossibility of getting into the system if you don’t play by its rules.

As someone hoping to one day engage with this system and maybe even make a living out of it, this was all pretty disheartening stuff. The industry certainly had its reasons for working this way, and I was happy to play along with it up to a point. But it was all the funny little unwritten “dos” and “don’ts” that were bothering me. Was it really so terrible to post your work online, if you later wanted a publishing house to take it seriously? Was self-publishing really as evil as everyone made it sound? Why was this confusing system the only path an author could take to get published?

And then while I was pondering, Nimona wandered into the publishing industry’s top-secret labs and started casually breaking all the rules.

Although there’s a growing number of graphic novels written or children and young adults, it’s not every day that my love of children’s literature overlaps with my love of webcomics. In fact, I’m pretty sure that in my entire academic experience it’s happened only once—with Noelle Stevenson’s hilarious and subversive “monk punk” webcomic Nimona. I fell in love with Nimona for its complicated characters, trope-savvy humor, and quirky art, all of which come together in a fantastic story that I can (and do) recommend to everyone. But Nimona remains particularly special to me for another reason entirely: the unusual way it came to be what it is today, shapeshifting from a free, independent webcomic into a published, award-winning graphic novel.

I first started reading Nimona back in late 2013, when it was about half finished and beginning to gather a noticeably large and adoring fandom online. At the same time, in my other life as a grad student with no time for reading silly things on the internet, I was learning about the children’s literature publishing industry. Manuscripts, agents, editors, imprints, print runs, age groups, rewrites, distribution, marketing. The pseudo-myth of royalties. The near-impossibility of getting into the system if you don’t play by its rules.

As someone hoping to one day engage with this system and maybe even make a living out of it, this was all pretty disheartening stuff. The industry certainly had its reasons for working this way, and I was happy to play along with it up to a point. But it was all the funny little unwritten “dos” and “don’ts” that were bothering me. Was it really so terrible to post your work online, if you later wanted a publishing house to take it seriously? Was self-publishing really as evil as everyone made it sound? Why was this confusing system the only path an author could take to get published?

And then while I was pondering, Nimona wandered into the publishing industry’s top-secret labs and started casually breaking all the rules.

First of all, it was a webcomic. Not just a normal comic, a comic posted twice a week on the internet (gasp), completely for free, without any guidance or input from an editor (gasp). From there, it caught the attention of an agent, who approached Stevenson unsolicited (gasp), rather than the other way around. With the assistance of said agent, it then got published by HarperCollins (GASP). Not just some comics-only publishing house or obscure indie press, HarperCollins, who bought the entire comic before it was complete or even had a finished script, and then allowed Stevenson to continue serializing it online through to the end.

With HarperCollins behind it, Nimona was suddenly eligible for the attention—and adoration—of not just the New York Times, but all five of the major children’s literature review journals. It became a New York Times bestseller. It won a National Book Honor.

It completely disregarded all the rules of the publishing industry, and yet succeeded.

First of all, it was a webcomic. Not just a normal comic, a comic posted twice a week on the internet (gasp), completely for free, without any guidance or input from an editor (gasp). From there, it caught the attention of an agent, who approached Stevenson unsolicited (gasp), rather than the other way around. With the assistance of said agent, it then got published by HarperCollins (GASP). Not just some comics-only publishing house or obscure indie press, HarperCollins, who bought the entire comic before it was complete or even had a finished script, and then allowed Stevenson to continue serializing it online through to the end.

With HarperCollins behind it, Nimona was suddenly eligible for the attention—and adoration—of not just the New York Times, but all five of the major children’s literature review journals. It became a New York Times bestseller. It won a National Book Honor.

It completely disregarded all the rules of the publishing industry, and yet succeeded.

Now, of course the publishing industry isn’t actually some sinister organization dabbling in science and weapons development (as far as we know, anyway). And I’m relieved Nimona didn’t somehow burn down the entire industry and then disappear into the night, leaving the rest of us to rebuild from the ruins. But I’ve never been able to resist rooting for the underdog. And I can’t help but be inspired by Noelle Stevenson for managing to do all that she’s done while still remaining true to herself and her shapeshifting monster of a story. Suggesting, even by example, that we should all chuck the publishing system and go it alone sounds to most like the rallying cry of a villain. But for most readers, Stevenson stands behind her work looking instead like a hero. I know she’s one of mine.

Now, of course the publishing industry isn’t actually some sinister organization dabbling in science and weapons development (as far as we know, anyway). And I’m relieved Nimona didn’t somehow burn down the entire industry and then disappear into the night, leaving the rest of us to rebuild from the ruins. But I’ve never been able to resist rooting for the underdog. And I can’t help but be inspired by Noelle Stevenson for managing to do all that she’s done while still remaining true to herself and her shapeshifting monster of a story. Suggesting, even by example, that we should all chuck the publishing system and go it alone sounds to most like the rallying cry of a villain. But for most readers, Stevenson stands behind her work looking instead like a hero. I know she’s one of mine.