Combating Fat Phobia in YA Lit

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

One of the biggest pet peeves of mine in YA lit and in our society more broadly is how poorly fat people — and I use “fat people” not as a pejorative phrase but as a description of a physical state of being — are rendered, treated, and discussed. More specifically, characters in YA tend to be depicted as oafish, as villains, or, most commonly and most problematically, as characters who have to overcome their weight in order to be seen as worthwhile or able to achieve their dreams, whatever they may be.

This isn’t a new issue. I’ve been keeping an eye on fat representation in YA for many years now. I can count on a single hand the books that depict a fat character as a whole, worthy being who can do what s/he wants to without being “held back” by their body. Those books, which I can recommend with no reservations whatsoever, include Isabel Quintero’s Gabi, A Girl in Pieces, Susan Vaught’s My Big Fat Manifesto, and Simmone Howell’s Everything Beautiful. I’ve yet to read Allen Zadoff’s Food, Girls, and Other Things I Can’t Have or Julie Murphy’s forthcoming Dumplin’ (out in September), but both come with high recommendations as doing fat characters with respect.

Before someone hops into the comments to suggest Eleanor & Park, the reason I don’t include that in my list of solid fat character depictions is that Rowell had to follow up her book with a blog post that answered the reader questions about Eleanor’s body. If you don’t lay it out there in numbers, and Rowell even says she doesn’t, then it’s not meant to be a takeaway. Readers ask this because it’s important to them to know. To be represented. To see themselves.

For the most part, when YA does fat characters and they’re done poorly, it’s not because the author is vicious or vindictive against fat characters. Rather, their experiences are so seeped in our problematic culture that teasing out those poorly worded phrases, depictions, or downright stereotypical scenes and situations (getting stuck in clothes you’re trying on or having a bench break beneath a character as s/he sits) is difficult.

Sometimes the slights aren’t slight though; in David Levithan’s Every Day, for example, the only body that “A” shows any disdain towards is the fat one, which is described in such a hurtful manner that even thinking about the passage makes me uncomfortable. “A” describes the obese body as one acquired through laziness and negligence that is downright “pathological.” Even a heroin addict is offered more compassion than the obese character.

Then there are the red flags that arise outside the author’s control yet still send hugely problematic messages about body size and weight: publicity/marketing and cover design:

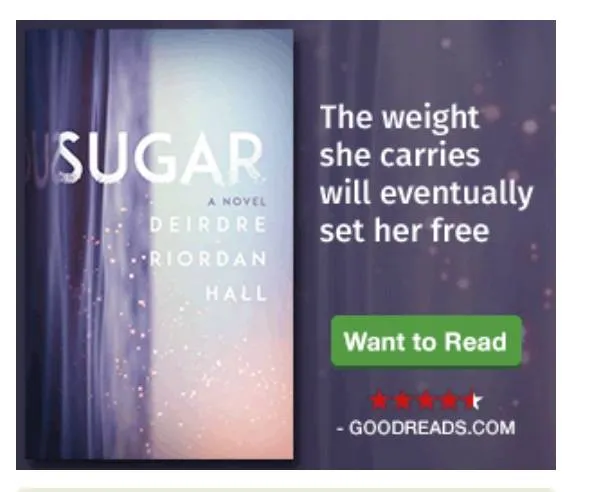

Sugar was pitched to me as a well-done story of a fat girl whose body isn’t the central “issue” of the book. Except, aside from that not being true — Sugar regularly falls into common problems associated with writing fat characters, including the grossly overused phrase that she’s “a skinny girl trapped in a fat body” — the marketing campaign for the book then turns Sugar’s body into the message.

In the top ad, Sugar’s weight “will eventually set her free.” Aside from not making any sense at all, her weight is the thing that does the talking/storytelling. In the bottom ad, it’s even worse: Sugar has a future that is “not weighed down by her body.” Not only does it describe her body as the problem, it directly contradicts the bigger ad, where the weight she carries will eventually “set her free.”

So what is it? Is her body holding her back and she’ll be better when she’s no longer “weighed down” by it or will her fat body actually set her free?

It doesn’t matter. In either case, her body is the story here. Her fat body is the story and it’s a problem to be overcome.

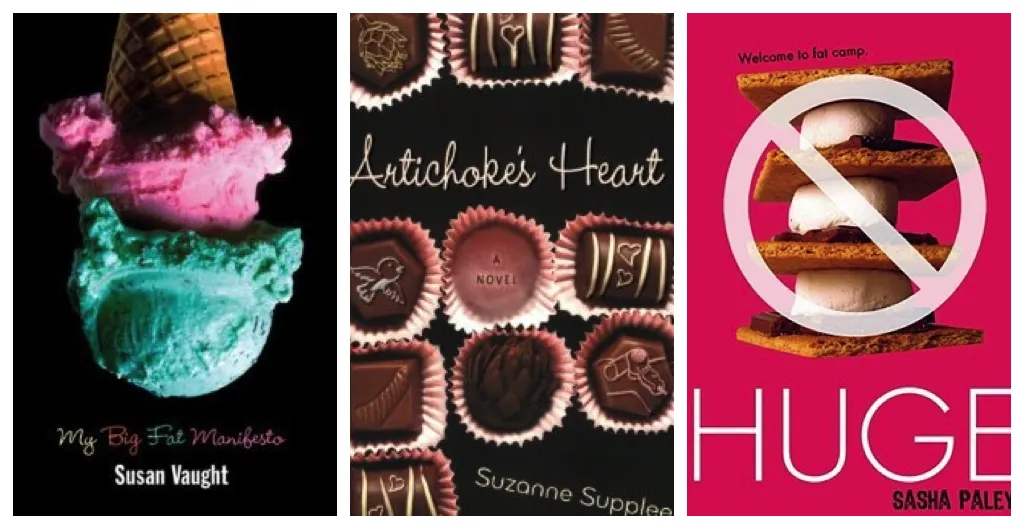

Book covers aren’t helping the situation, either. Finding a fat character on a YA book cover is nearly impossible. Instead, we get things like food:

Sugar was pitched to me as a well-done story of a fat girl whose body isn’t the central “issue” of the book. Except, aside from that not being true — Sugar regularly falls into common problems associated with writing fat characters, including the grossly overused phrase that she’s “a skinny girl trapped in a fat body” — the marketing campaign for the book then turns Sugar’s body into the message.

In the top ad, Sugar’s weight “will eventually set her free.” Aside from not making any sense at all, her weight is the thing that does the talking/storytelling. In the bottom ad, it’s even worse: Sugar has a future that is “not weighed down by her body.” Not only does it describe her body as the problem, it directly contradicts the bigger ad, where the weight she carries will eventually “set her free.”

So what is it? Is her body holding her back and she’ll be better when she’s no longer “weighed down” by it or will her fat body actually set her free?

It doesn’t matter. In either case, her body is the story here. Her fat body is the story and it’s a problem to be overcome.

Book covers aren’t helping the situation, either. Finding a fat character on a YA book cover is nearly impossible. Instead, we get things like food:

Fortunately in the case of the Vaught book, there’s a second cover that’s much better. Likewise, with a lot of work, one could seek out a cover for Paley’s book that features Nikki Blonsky on it that was created in conjunction with the ABC Family television show based on the story.

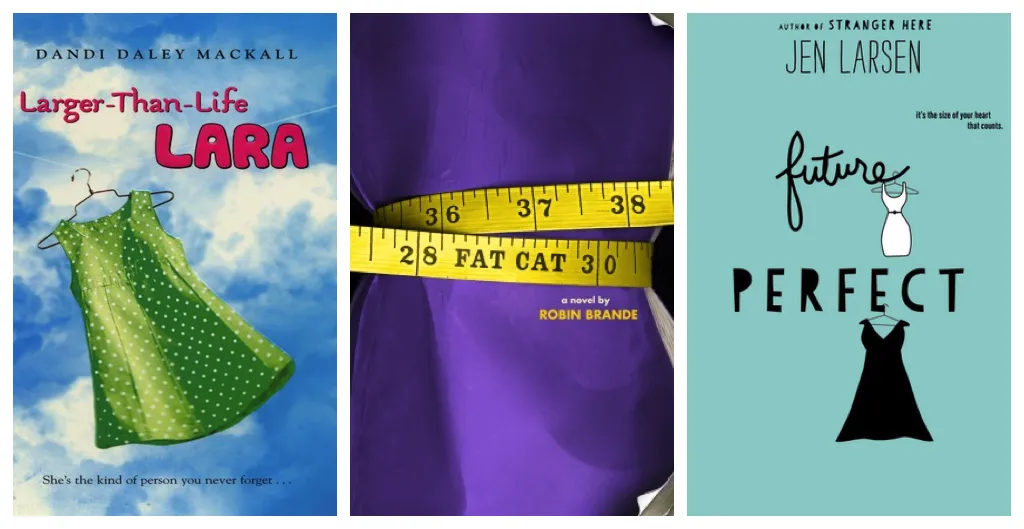

Fat characters also get covers with clothing or some indication of size on them:

Fortunately in the case of the Vaught book, there’s a second cover that’s much better. Likewise, with a lot of work, one could seek out a cover for Paley’s book that features Nikki Blonsky on it that was created in conjunction with the ABC Family television show based on the story.

Fat characters also get covers with clothing or some indication of size on them:

It’s gotten to the point where a book featuring food or empty clothing on the cover signals to me as a reader that the book is likely about a fat character.

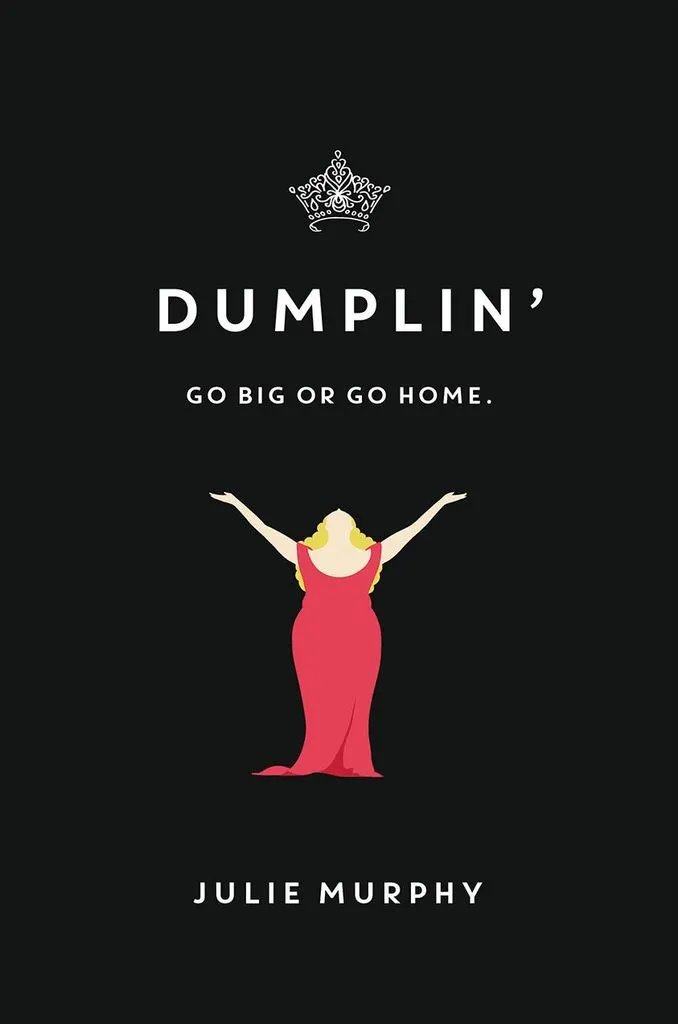

That would be why covers like this one matter so much:

It’s gotten to the point where a book featuring food or empty clothing on the cover signals to me as a reader that the book is likely about a fat character.

That would be why covers like this one matter so much:

It’s a fat girl. She’s wearing a dress. She’s not hiding her body. And the tag line? We get a play on the idea she’s fat but it never renders her body the object of the story. Instead, she’s owning the hell out of her dress, she’s standing in a position that’s one of pride and love, and the crown over the title? The cover for Dumplin is a complete and total winner.

The more that we see fat depicted in covers and not belittled or sold as the problem to be overcome in a story, the better messages we send to readers.

But perhaps — despite how I’ve laid it out here — it’s not all doom and gloom. I like to think that Murphy’s book is a big corner being turned. I also like to think that books like Quintero’s, mentioned above, which become highly decorated with awards and recognitions, offer a way into just how a fat character can have a whole story that isn’t solely about his or her fatness.

And maybe, just maybe, we can also thank graphic novels and comics aimed at the YA audience.

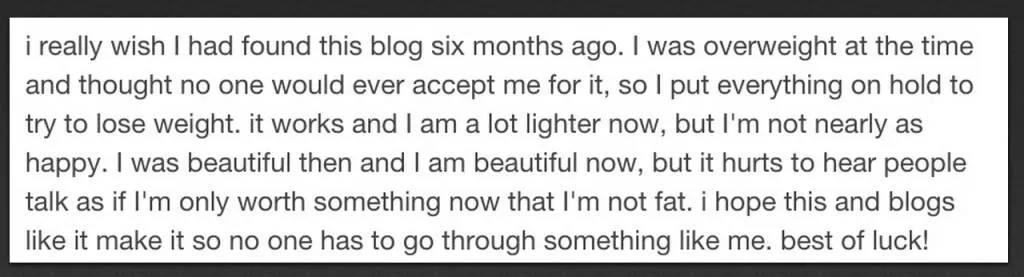

Over the last few months, I’ve been talking more openly about fatness in YA, and along with three librarians who find discussing issues of body acceptance to be important, put together the Size Acceptance in YA Tumblr. What’s been most exciting about the project, aside from being able to talk about size acceptance openly with readers who are interested in that, is the reader feedback we’ve received.

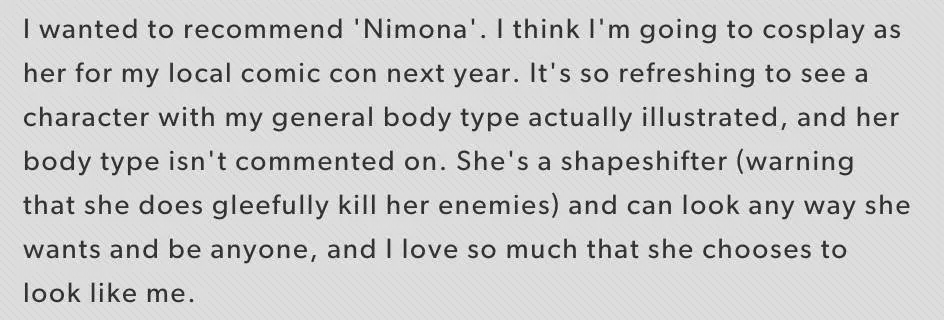

It was reader feedback that got the wheels turning for me about depictions of fatness in YA-geared graphic novels:

It’s a fat girl. She’s wearing a dress. She’s not hiding her body. And the tag line? We get a play on the idea she’s fat but it never renders her body the object of the story. Instead, she’s owning the hell out of her dress, she’s standing in a position that’s one of pride and love, and the crown over the title? The cover for Dumplin is a complete and total winner.

The more that we see fat depicted in covers and not belittled or sold as the problem to be overcome in a story, the better messages we send to readers.

But perhaps — despite how I’ve laid it out here — it’s not all doom and gloom. I like to think that Murphy’s book is a big corner being turned. I also like to think that books like Quintero’s, mentioned above, which become highly decorated with awards and recognitions, offer a way into just how a fat character can have a whole story that isn’t solely about his or her fatness.

And maybe, just maybe, we can also thank graphic novels and comics aimed at the YA audience.

Over the last few months, I’ve been talking more openly about fatness in YA, and along with three librarians who find discussing issues of body acceptance to be important, put together the Size Acceptance in YA Tumblr. What’s been most exciting about the project, aside from being able to talk about size acceptance openly with readers who are interested in that, is the reader feedback we’ve received.

It was reader feedback that got the wheels turning for me about depictions of fatness in YA-geared graphic novels:

What a powerful comment.

Noelle Stevenson’s Nimona is an outstanding example of how fatness can be done without fatness ever being central to the story. While Nimona is fat, that’s not the story. Rather, she’s a fat girl who gets to have an entire arc without her fatness being used as the catalyst, as the thing to overcome, as the object of ridicule, shame, or misfortune.

What a powerful comment.

Noelle Stevenson’s Nimona is an outstanding example of how fatness can be done without fatness ever being central to the story. While Nimona is fat, that’s not the story. Rather, she’s a fat girl who gets to have an entire arc without her fatness being used as the catalyst, as the thing to overcome, as the object of ridicule, shame, or misfortune.

More, as the comment said, the fact Nimona chooses to have the body she does sends a really important, memorable, and accepting message.

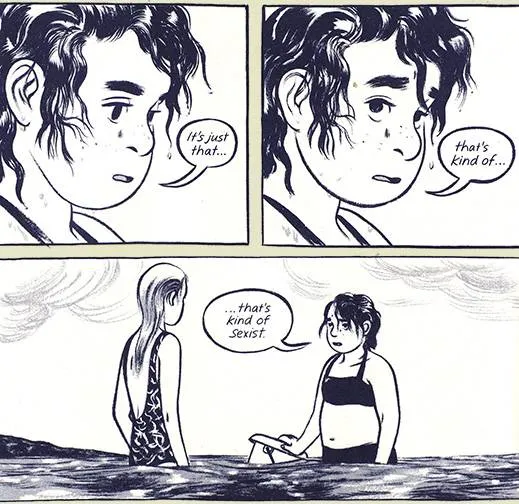

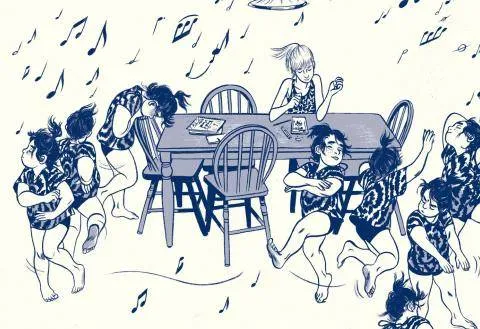

Nimona isn’t alone in depicting fatter bodies in graphic novels, either, and it isn’t alone in offering a fat character who doesn’t fixate on her body throughout the story. Check out the way that Jillian and Mariko Tamaki draw Windy, one of their main characters, in the award-winning This One Summer:

More, as the comment said, the fact Nimona chooses to have the body she does sends a really important, memorable, and accepting message.

Nimona isn’t alone in depicting fatter bodies in graphic novels, either, and it isn’t alone in offering a fat character who doesn’t fixate on her body throughout the story. Check out the way that Jillian and Mariko Tamaki draw Windy, one of their main characters, in the award-winning This One Summer:

Not only is Windy fat, she’s smart, and she’s able to have a damn good time without her body becoming at all a part of the story (even though it is completely part of her story because it is her body).

Consciously drawing a fat girl in a bathing suit is radical. So is having her dance and enjoy herself. Seeing this, especially in YA, matters tremendously. A takeaway, even though it’s not the core of the story, is that fat girls can have stories, can love their bodies, and can enjoy having a body.

Another great fat girl in comics? Anda in Cory Doctorow and Jen Wang’s In Real Life. Even though her virtual world avatar isn’t a fat girl, she is, and her body isn’t an issue in the story. Here’s a scene that’s especially memorable: Anda leaning over her tub dying her hair to match the color of the hair in her avatar. She’s not hiding. There’s not a towel around her body. Her fat body is there for us to see.

Not only is Windy fat, she’s smart, and she’s able to have a damn good time without her body becoming at all a part of the story (even though it is completely part of her story because it is her body).

Consciously drawing a fat girl in a bathing suit is radical. So is having her dance and enjoy herself. Seeing this, especially in YA, matters tremendously. A takeaway, even though it’s not the core of the story, is that fat girls can have stories, can love their bodies, and can enjoy having a body.

Another great fat girl in comics? Anda in Cory Doctorow and Jen Wang’s In Real Life. Even though her virtual world avatar isn’t a fat girl, she is, and her body isn’t an issue in the story. Here’s a scene that’s especially memorable: Anda leaning over her tub dying her hair to match the color of the hair in her avatar. She’s not hiding. There’s not a towel around her body. Her fat body is there for us to see.

There is a short body shaming moment in the illustrations, but it’s not the focus and readers who see it and “get” it will know that it’s not about belittling Anda’s body. Rather, it’s a commentary on how pervasive and problematic fat shaming is. Even our closest friends and family members can screw up when they talk to us.

Talking about the depictions of fatness in YA matters because these messages do indeed reach readers. For teenagers, these messages are already hurled at them through every waking moment. Our culture thrives upon insecurities, and fatness is an easy one to target. “Health” and the “obesity epidemic” sound like good and nice reasons to “care” about fat people, except they’re excuses to continue being careless. Fat people know they’re fat. You don’t have to tell them.

But you should damn well let them see themselves in ways where their bodies aren’t commodified, aren’t a source of daily hell, or render them as worthless beings who have no future unless they can “overcome” their state of fat.

Because more often than not, these are the messages fat people, including myself, contend with daily.

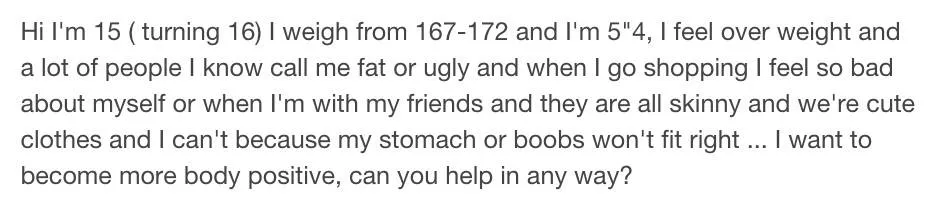

I live for the day where people don’t need to reach out like this:

There is a short body shaming moment in the illustrations, but it’s not the focus and readers who see it and “get” it will know that it’s not about belittling Anda’s body. Rather, it’s a commentary on how pervasive and problematic fat shaming is. Even our closest friends and family members can screw up when they talk to us.

Talking about the depictions of fatness in YA matters because these messages do indeed reach readers. For teenagers, these messages are already hurled at them through every waking moment. Our culture thrives upon insecurities, and fatness is an easy one to target. “Health” and the “obesity epidemic” sound like good and nice reasons to “care” about fat people, except they’re excuses to continue being careless. Fat people know they’re fat. You don’t have to tell them.

But you should damn well let them see themselves in ways where their bodies aren’t commodified, aren’t a source of daily hell, or render them as worthless beings who have no future unless they can “overcome” their state of fat.

Because more often than not, these are the messages fat people, including myself, contend with daily.

I live for the day where people don’t need to reach out like this:

I live for the day that no 15, 16, 17, 30, 40 year old has to say they feel invisible, that their bodies aren’t okay, or that being fat is the worst thing in the world.

We can do better.

We need to do better.

And YA books can absolutely be a solid starting place. Wouldn’t it be great to have too many books to choose from to hand to a teen where a fat character is simply fat — and uses the word — rather than have to rely on the same small handful?

Let’s hope these YA graphic novels, which offer visual body diversity, continue pushing us toward doing better.

I live for the day that no 15, 16, 17, 30, 40 year old has to say they feel invisible, that their bodies aren’t okay, or that being fat is the worst thing in the world.

We can do better.

We need to do better.

And YA books can absolutely be a solid starting place. Wouldn’t it be great to have too many books to choose from to hand to a teen where a fat character is simply fat — and uses the word — rather than have to rely on the same small handful?

Let’s hope these YA graphic novels, which offer visual body diversity, continue pushing us toward doing better.

Fortunately in the case of the Vaught book, there’s a second cover that’s much better. Likewise, with a lot of work, one could seek out a cover for Paley’s book that features Nikki Blonsky on it that was created in conjunction with the ABC Family television show based on the story.

Fat characters also get covers with clothing or some indication of size on them:

Fortunately in the case of the Vaught book, there’s a second cover that’s much better. Likewise, with a lot of work, one could seek out a cover for Paley’s book that features Nikki Blonsky on it that was created in conjunction with the ABC Family television show based on the story.

Fat characters also get covers with clothing or some indication of size on them:

It’s gotten to the point where a book featuring food or empty clothing on the cover signals to me as a reader that the book is likely about a fat character.

That would be why covers like this one matter so much:

It’s gotten to the point where a book featuring food or empty clothing on the cover signals to me as a reader that the book is likely about a fat character.

That would be why covers like this one matter so much:

It’s a fat girl. She’s wearing a dress. She’s not hiding her body. And the tag line? We get a play on the idea she’s fat but it never renders her body the object of the story. Instead, she’s owning the hell out of her dress, she’s standing in a position that’s one of pride and love, and the crown over the title? The cover for Dumplin is a complete and total winner.

The more that we see fat depicted in covers and not belittled or sold as the problem to be overcome in a story, the better messages we send to readers.

But perhaps — despite how I’ve laid it out here — it’s not all doom and gloom. I like to think that Murphy’s book is a big corner being turned. I also like to think that books like Quintero’s, mentioned above, which become highly decorated with awards and recognitions, offer a way into just how a fat character can have a whole story that isn’t solely about his or her fatness.

And maybe, just maybe, we can also thank graphic novels and comics aimed at the YA audience.

Over the last few months, I’ve been talking more openly about fatness in YA, and along with three librarians who find discussing issues of body acceptance to be important, put together the Size Acceptance in YA Tumblr. What’s been most exciting about the project, aside from being able to talk about size acceptance openly with readers who are interested in that, is the reader feedback we’ve received.

It was reader feedback that got the wheels turning for me about depictions of fatness in YA-geared graphic novels:

It’s a fat girl. She’s wearing a dress. She’s not hiding her body. And the tag line? We get a play on the idea she’s fat but it never renders her body the object of the story. Instead, she’s owning the hell out of her dress, she’s standing in a position that’s one of pride and love, and the crown over the title? The cover for Dumplin is a complete and total winner.

The more that we see fat depicted in covers and not belittled or sold as the problem to be overcome in a story, the better messages we send to readers.

But perhaps — despite how I’ve laid it out here — it’s not all doom and gloom. I like to think that Murphy’s book is a big corner being turned. I also like to think that books like Quintero’s, mentioned above, which become highly decorated with awards and recognitions, offer a way into just how a fat character can have a whole story that isn’t solely about his or her fatness.

And maybe, just maybe, we can also thank graphic novels and comics aimed at the YA audience.

Over the last few months, I’ve been talking more openly about fatness in YA, and along with three librarians who find discussing issues of body acceptance to be important, put together the Size Acceptance in YA Tumblr. What’s been most exciting about the project, aside from being able to talk about size acceptance openly with readers who are interested in that, is the reader feedback we’ve received.

It was reader feedback that got the wheels turning for me about depictions of fatness in YA-geared graphic novels:

What a powerful comment.

Noelle Stevenson’s Nimona is an outstanding example of how fatness can be done without fatness ever being central to the story. While Nimona is fat, that’s not the story. Rather, she’s a fat girl who gets to have an entire arc without her fatness being used as the catalyst, as the thing to overcome, as the object of ridicule, shame, or misfortune.

What a powerful comment.

Noelle Stevenson’s Nimona is an outstanding example of how fatness can be done without fatness ever being central to the story. While Nimona is fat, that’s not the story. Rather, she’s a fat girl who gets to have an entire arc without her fatness being used as the catalyst, as the thing to overcome, as the object of ridicule, shame, or misfortune.

More, as the comment said, the fact Nimona chooses to have the body she does sends a really important, memorable, and accepting message.

Nimona isn’t alone in depicting fatter bodies in graphic novels, either, and it isn’t alone in offering a fat character who doesn’t fixate on her body throughout the story. Check out the way that Jillian and Mariko Tamaki draw Windy, one of their main characters, in the award-winning This One Summer:

More, as the comment said, the fact Nimona chooses to have the body she does sends a really important, memorable, and accepting message.

Nimona isn’t alone in depicting fatter bodies in graphic novels, either, and it isn’t alone in offering a fat character who doesn’t fixate on her body throughout the story. Check out the way that Jillian and Mariko Tamaki draw Windy, one of their main characters, in the award-winning This One Summer:

Not only is Windy fat, she’s smart, and she’s able to have a damn good time without her body becoming at all a part of the story (even though it is completely part of her story because it is her body).

Consciously drawing a fat girl in a bathing suit is radical. So is having her dance and enjoy herself. Seeing this, especially in YA, matters tremendously. A takeaway, even though it’s not the core of the story, is that fat girls can have stories, can love their bodies, and can enjoy having a body.

Another great fat girl in comics? Anda in Cory Doctorow and Jen Wang’s In Real Life. Even though her virtual world avatar isn’t a fat girl, she is, and her body isn’t an issue in the story. Here’s a scene that’s especially memorable: Anda leaning over her tub dying her hair to match the color of the hair in her avatar. She’s not hiding. There’s not a towel around her body. Her fat body is there for us to see.

Not only is Windy fat, she’s smart, and she’s able to have a damn good time without her body becoming at all a part of the story (even though it is completely part of her story because it is her body).

Consciously drawing a fat girl in a bathing suit is radical. So is having her dance and enjoy herself. Seeing this, especially in YA, matters tremendously. A takeaway, even though it’s not the core of the story, is that fat girls can have stories, can love their bodies, and can enjoy having a body.

Another great fat girl in comics? Anda in Cory Doctorow and Jen Wang’s In Real Life. Even though her virtual world avatar isn’t a fat girl, she is, and her body isn’t an issue in the story. Here’s a scene that’s especially memorable: Anda leaning over her tub dying her hair to match the color of the hair in her avatar. She’s not hiding. There’s not a towel around her body. Her fat body is there for us to see.

There is a short body shaming moment in the illustrations, but it’s not the focus and readers who see it and “get” it will know that it’s not about belittling Anda’s body. Rather, it’s a commentary on how pervasive and problematic fat shaming is. Even our closest friends and family members can screw up when they talk to us.

Talking about the depictions of fatness in YA matters because these messages do indeed reach readers. For teenagers, these messages are already hurled at them through every waking moment. Our culture thrives upon insecurities, and fatness is an easy one to target. “Health” and the “obesity epidemic” sound like good and nice reasons to “care” about fat people, except they’re excuses to continue being careless. Fat people know they’re fat. You don’t have to tell them.

But you should damn well let them see themselves in ways where their bodies aren’t commodified, aren’t a source of daily hell, or render them as worthless beings who have no future unless they can “overcome” their state of fat.

Because more often than not, these are the messages fat people, including myself, contend with daily.

I live for the day where people don’t need to reach out like this:

There is a short body shaming moment in the illustrations, but it’s not the focus and readers who see it and “get” it will know that it’s not about belittling Anda’s body. Rather, it’s a commentary on how pervasive and problematic fat shaming is. Even our closest friends and family members can screw up when they talk to us.

Talking about the depictions of fatness in YA matters because these messages do indeed reach readers. For teenagers, these messages are already hurled at them through every waking moment. Our culture thrives upon insecurities, and fatness is an easy one to target. “Health” and the “obesity epidemic” sound like good and nice reasons to “care” about fat people, except they’re excuses to continue being careless. Fat people know they’re fat. You don’t have to tell them.

But you should damn well let them see themselves in ways where their bodies aren’t commodified, aren’t a source of daily hell, or render them as worthless beings who have no future unless they can “overcome” their state of fat.

Because more often than not, these are the messages fat people, including myself, contend with daily.

I live for the day where people don’t need to reach out like this:

I live for the day that no 15, 16, 17, 30, 40 year old has to say they feel invisible, that their bodies aren’t okay, or that being fat is the worst thing in the world.

We can do better.

We need to do better.

And YA books can absolutely be a solid starting place. Wouldn’t it be great to have too many books to choose from to hand to a teen where a fat character is simply fat — and uses the word — rather than have to rely on the same small handful?

Let’s hope these YA graphic novels, which offer visual body diversity, continue pushing us toward doing better.

I live for the day that no 15, 16, 17, 30, 40 year old has to say they feel invisible, that their bodies aren’t okay, or that being fat is the worst thing in the world.

We can do better.

We need to do better.

And YA books can absolutely be a solid starting place. Wouldn’t it be great to have too many books to choose from to hand to a teen where a fat character is simply fat — and uses the word — rather than have to rely on the same small handful?

Let’s hope these YA graphic novels, which offer visual body diversity, continue pushing us toward doing better.