100 Recommended Books by Arab Women for Your 2017 Reading Resolutions

Translated from the Arabic

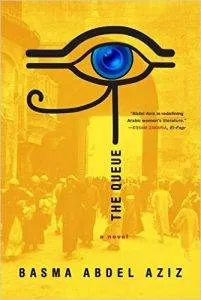

Recent books by Arab women 1) The Queue, by Basma Abdel Aziz, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette (2016). The Queue – an exploration of post-2011 Egypt originally published in 2013 – is a work of magico-political realism, the literary child of Egyptian Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz and English writer George Orwell, with a bonus: Abdel Aziz is one of the few to really write down the details of Egyptian women’s lives and to craft female characters who come from a wide variety of social classes. If you need them: 5 more reasons to read this book.

1) The Queue, by Basma Abdel Aziz, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette (2016). The Queue – an exploration of post-2011 Egypt originally published in 2013 – is a work of magico-political realism, the literary child of Egyptian Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz and English writer George Orwell, with a bonus: Abdel Aziz is one of the few to really write down the details of Egyptian women’s lives and to craft female characters who come from a wide variety of social classes. If you need them: 5 more reasons to read this book.

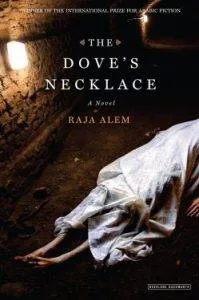

2) The Dove’s Necklace, by Raja Alem, trans. Katherine Halls and Adam Talib (2016). Alem’s The Dove’s Necklace has the distinction of being the only book by a woman to have won (well, co-won) the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. This book is a wicked, wild ride through a fantastical fictional Mecca. To get to know more about the city, read it alongside Ziauddin Sardar’s Mecca.

2) The Dove’s Necklace, by Raja Alem, trans. Katherine Halls and Adam Talib (2016). Alem’s The Dove’s Necklace has the distinction of being the only book by a woman to have won (well, co-won) the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. This book is a wicked, wild ride through a fantastical fictional Mecca. To get to know more about the city, read it alongside Ziauddin Sardar’s Mecca.

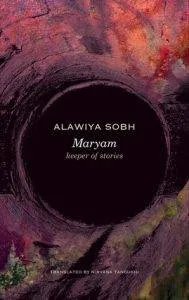

3) Maryam, Keeper of Stories, by Alawiyya Sobh, trans. Nirvana Tanoukhi (2016). There is even a literary award named for Alawiyya Sobh (the “Alawiya Sobh Literary Criticism Award”), but this is the first of her works translated into English. This acclaimed novel, originally published in Arabic in 2002, doesn’t just tackle the content of Lebanese women’s lives. Its form—1,001 Nights-esque, interlinked tales—is also womanish. The action doesn’t follow the forward-marching masculine world of politics and business. Even when women protest or pick up weapons, the narrative stays focused on the circularity of relationships. The book also gives respectful attention to village superstitions, soap operas, and other “low” genres associated with women. Read a review of Sobh’s “feminist frisson.”

3) Maryam, Keeper of Stories, by Alawiyya Sobh, trans. Nirvana Tanoukhi (2016). There is even a literary award named for Alawiyya Sobh (the “Alawiya Sobh Literary Criticism Award”), but this is the first of her works translated into English. This acclaimed novel, originally published in Arabic in 2002, doesn’t just tackle the content of Lebanese women’s lives. Its form—1,001 Nights-esque, interlinked tales—is also womanish. The action doesn’t follow the forward-marching masculine world of politics and business. Even when women protest or pick up weapons, the narrative stays focused on the circularity of relationships. The book also gives respectful attention to village superstitions, soap operas, and other “low” genres associated with women. Read a review of Sobh’s “feminist frisson.”

4) 32, by Sahar Mandour, trans. Nicole Fares (2016). Mandour is often and rightly mentioned as one of the up-and-coming-est Arab women writers. This, Mandour’s third novel, is an examination of the lives of five Lebanese women and a Sri Lankan domestic worker. You can read an excerpt in World Literature Today.

4) 32, by Sahar Mandour, trans. Nicole Fares (2016). Mandour is often and rightly mentioned as one of the up-and-coming-est Arab women writers. This, Mandour’s third novel, is an examination of the lives of five Lebanese women and a Sri Lankan domestic worker. You can read an excerpt in World Literature Today.

5) Ali and His Russian Mother, Alexandra Chretieh, trans. Michelle Hartman (2015). Ali and His Russian Mother is a character-driven portrait that centers on two individuals: the titular gay man, Ali, and a straight female narrator who doesn’t see herself as homophobic, because, you know, she’s got gay friends. It’s full of Chreiteh’s characteristic humor and psychological insight, with a particular focus on young people in Beirut. The Ukrainian-Lebanese gay man, who also freaks out over the discovery that one of his ancestors was Jewish, is portrayed in wonderful, self-hating, over-the-top glory. Read an interview with Chretieh about writing on menstruation in Modern Standard Arabic.

5) Ali and His Russian Mother, Alexandra Chretieh, trans. Michelle Hartman (2015). Ali and His Russian Mother is a character-driven portrait that centers on two individuals: the titular gay man, Ali, and a straight female narrator who doesn’t see herself as homophobic, because, you know, she’s got gay friends. It’s full of Chreiteh’s characteristic humor and psychological insight, with a particular focus on young people in Beirut. The Ukrainian-Lebanese gay man, who also freaks out over the discovery that one of his ancestors was Jewish, is portrayed in wonderful, self-hating, over-the-top glory. Read an interview with Chretieh about writing on menstruation in Modern Standard Arabic.

6) Oh, Salaam!, by Najwa Barakat, trans. Luke Leafgren (2015). Luqman, the novel’s protagonist, is a young former militiaman, trying to make a living in a post-war Lebanon. Is there a post-war Lebanon? Or are people still trapped in the same cycles, the same behaviors that got them through the 15-year war. As Eyad Houssami writes, this novel’s crudeness is also what makes it witty and entertaining.

6) Oh, Salaam!, by Najwa Barakat, trans. Luke Leafgren (2015). Luqman, the novel’s protagonist, is a young former militiaman, trying to make a living in a post-war Lebanon. Is there a post-war Lebanon? Or are people still trapped in the same cycles, the same behaviors that got them through the 15-year war. As Eyad Houssami writes, this novel’s crudeness is also what makes it witty and entertaining.

7) The Woman of Tantoura, by Radwa Ashour, trans. Kay Heikkinen (2015). One of Ashour’s most popular and enjoyable novels, a multigenerational epic about the many travels of a Palestininan woman trying to tell her story and keep together her family. Particularly insightful about women and sons.

7) The Woman of Tantoura, by Radwa Ashour, trans. Kay Heikkinen (2015). One of Ashour’s most popular and enjoyable novels, a multigenerational epic about the many travels of a Palestininan woman trying to tell her story and keep together her family. Particularly insightful about women and sons.

8) Other Lives, by Iman Humaydan, trans. Michelle Hartman (2014). Humaydan and Hartman have released three books in the last two years. The two others are the layered Weight of Paradise and the excellent short-story collection Beirut Noir, where half of the stories are by women. Other Lives moves between a Shouf mountain village to Beirut, Melbourne, Nairobi, Mombasa, and Cape Town, and to all the ghosts — and other possible lives — that Myriam must confront, things she left behind when she emigrated to Australia. Read an excerpt.

8) Other Lives, by Iman Humaydan, trans. Michelle Hartman (2014). Humaydan and Hartman have released three books in the last two years. The two others are the layered Weight of Paradise and the excellent short-story collection Beirut Noir, where half of the stories are by women. Other Lives moves between a Shouf mountain village to Beirut, Melbourne, Nairobi, Mombasa, and Cape Town, and to all the ghosts — and other possible lives — that Myriam must confront, things she left behind when she emigrated to Australia. Read an excerpt.

9) Beyond Love, by Hadiya Hussein, trans. Ikram Masmoudi (2012). Characters in Beyond Love — they are mostly women, men having died or disappeared — find memories of their home country, Iraq, painful. Yet these shifting memories are also irresistible. As one character says, “we’re eager to torture ourselves and whip our souls” with recollections “for reasons we don’t understand.” The novel’s foreground action is set in Jordan, just after the First Gulf War in 1991. That’s when Iraq’s sudden and crushing defeat sparked both an anti-regime uprising in the south as well as severe crackdowns from the state. As she waits in Jordan, Huda stumbles into two men who might have loved her.

9) Beyond Love, by Hadiya Hussein, trans. Ikram Masmoudi (2012). Characters in Beyond Love — they are mostly women, men having died or disappeared — find memories of their home country, Iraq, painful. Yet these shifting memories are also irresistible. As one character says, “we’re eager to torture ourselves and whip our souls” with recollections “for reasons we don’t understand.” The novel’s foreground action is set in Jordan, just after the First Gulf War in 1991. That’s when Iraq’s sudden and crushing defeat sparked both an anti-regime uprising in the south as well as severe crackdowns from the state. As she waits in Jordan, Huda stumbles into two men who might have loved her.

10) Of Noble Origins, by Sahar Khalifeh, trans. Aida Bamia (2012). Winner of the prestigious Mohamed Zafzaf prize, Khalifeh is a strong and prolific chronicler of different moments in Palestinian history. This takes us before 1948, the establishment of Israel, when so many Palestinians were forced out of their homes and turned into refugees, from the point of view of a number of different women. It’s similar to Elias Khoury’s seminal and feminine As Though She Were Sleeping, yet Khalifeh is less interested in great shifts, and more interested in the rough individual lives of women. Of Noble Origins is unusual in that it treats the lives of Palestinian Christians, Palestinian Muslims, Jewish immigrants, and British colonial leadership with an equal narrative interest.

10) Of Noble Origins, by Sahar Khalifeh, trans. Aida Bamia (2012). Winner of the prestigious Mohamed Zafzaf prize, Khalifeh is a strong and prolific chronicler of different moments in Palestinian history. This takes us before 1948, the establishment of Israel, when so many Palestinians were forced out of their homes and turned into refugees, from the point of view of a number of different women. It’s similar to Elias Khoury’s seminal and feminine As Though She Were Sleeping, yet Khalifeh is less interested in great shifts, and more interested in the rough individual lives of women. Of Noble Origins is unusual in that it treats the lives of Palestinian Christians, Palestinian Muslims, Jewish immigrants, and British colonial leadership with an equal narrative interest.

11) Always Coca-Cola, by Alexandra Chrietieh, trans. Michelle Hartman (2011). This book is a witty look at women’s lives in Lebanon in and around the lens of multinational brands that colonize and organize our bodies. Indeed, throughout the book, there is an absurd all-pervasiveness to global corporate brands such as Coca-Cola, Always and Starbucks. Even as Abeer is being raped, a Coca-Cola advertisement looms crazily over her attacker’s shoulder. You can read an excerpt online.

11) Always Coca-Cola, by Alexandra Chrietieh, trans. Michelle Hartman (2011). This book is a witty look at women’s lives in Lebanon in and around the lens of multinational brands that colonize and organize our bodies. Indeed, throughout the book, there is an absurd all-pervasiveness to global corporate brands such as Coca-Cola, Always and Starbucks. Even as Abeer is being raped, a Coca-Cola advertisement looms crazily over her attacker’s shoulder. You can read an excerpt online.

12) Spectres, by Radwa Ashour, trans. Barbara Romaine (2011). Winner of the Cairo International Book Fair Prize and runner-up for a Banipal translation prize, Spectres is both memoir and fiction, alternating between the stories of Radwa and Shagar: two women born the same day, one a (real) professor of literature, one a (shadow) professor of history. A discussion of Egyptian literature and history while also participating and playing with it.

12) Spectres, by Radwa Ashour, trans. Barbara Romaine (2011). Winner of the Cairo International Book Fair Prize and runner-up for a Banipal translation prize, Spectres is both memoir and fiction, alternating between the stories of Radwa and Shagar: two women born the same day, one a (real) professor of literature, one a (shadow) professor of history. A discussion of Egyptian literature and history while also participating and playing with it.

13) Judgment Day, by Rasha al-Ameer, trans. Jonathan Wright (2011). This is a dense, interesting philosophical novel in which the narrator, an imam, changes as he writes his memoir, a tribute to the one he loves. Throughout he reflects upon religion and the rivalry between the Quran and poetry, here particularly the great tenth century poet Mutanabbi. When asked to recommend a work by another Arab woman writer, this was the choice of Iraqi novelist Inaam Kachachi. You can read an interview with Wright about the process of translating this novel.

13) Judgment Day, by Rasha al-Ameer, trans. Jonathan Wright (2011). This is a dense, interesting philosophical novel in which the narrator, an imam, changes as he writes his memoir, a tribute to the one he loves. Throughout he reflects upon religion and the rivalry between the Quran and poetry, here particularly the great tenth century poet Mutanabbi. When asked to recommend a work by another Arab woman writer, this was the choice of Iraqi novelist Inaam Kachachi. You can read an interview with Wright about the process of translating this novel.

14) I Want to Get Married! by Ghada Abdel Aal, trans. Nora Eltahawy (2010). The cover is a bit misleading (this is about a middle-class Egyptian woman, not a twentysomething American), and the footnoting a bit overdone. But this over-the-top satiric portrait of contemporary Egyptian suitors, made into a popular TV series in Cairo, is wonderfully warm and funny. There have been criticism of the politics of the book — Why do people want to get married? Why put normative courtship rituals at the book’s center? Is Ghada critiquing current social practices or strengthening them? — but hey. It’s funny.

14) I Want to Get Married! by Ghada Abdel Aal, trans. Nora Eltahawy (2010). The cover is a bit misleading (this is about a middle-class Egyptian woman, not a twentysomething American), and the footnoting a bit overdone. But this over-the-top satiric portrait of contemporary Egyptian suitors, made into a popular TV series in Cairo, is wonderfully warm and funny. There have been criticism of the politics of the book — Why do people want to get married? Why put normative courtship rituals at the book’s center? Is Ghada critiquing current social practices or strengthening them? — but hey. It’s funny.

15) Touch, by Adania Shibli, trans. Paula Haydar (2010). This made the longlist for the Best Translated Book Award in 2011, surely for its prose-poetic insight into the mind of an eight-year-old girl who can hardly grasp what’s going on around her, politically, in Palestine, and is instead drawn to the colors, tastes, and smells that she can hold onto. As the narrator is on her way to a funeral, she obsesses about covering a hole in her clothing:

15) Touch, by Adania Shibli, trans. Paula Haydar (2010). This made the longlist for the Best Translated Book Award in 2011, surely for its prose-poetic insight into the mind of an eight-year-old girl who can hardly grasp what’s going on around her, politically, in Palestine, and is instead drawn to the colors, tastes, and smells that she can hold onto. As the narrator is on her way to a funeral, she obsesses about covering a hole in her clothing:

The pushing became harder and harsher, and each time it would force her hand away from the hole, so she would press on it harder and harder, using all her strength, including that in her right hand. That hand now had weakened its hold on the bottle, and a little black liquid leaked out with each step she was pushed backward.

Also: 16) We Are All Equally Far from Love, by Adania Shibli, trans. Paul Starkey (2012) Novels: Modern classics 17) Stone of Laughter, by Hoda Barakat, trans. Sophie Bennett (1990). The Lebanese Civil War sent an earthquake through Lebanese literature, and its effects are still being written and felt. Hoda Barakat’s novels have been at the center of this movement, and Stone of Laughter is one of her key works. When asked to recommend other Arab women writers, novelist Mansoura Ezz Eldin, and she said: “The novel that I’ve loved the most by an Arab woman writer is Hoda Barakat’s Stone of Laughter, which I read for the first time when the Egyptian edition was issued in 1998, and this was the first time I knew her writing. I bought it during the last two years of exams during university from a newspaper-and-bookseller who stood in front of the University of Cairo’s main gate, after its cover grabbed my attention.

“I read the first pages and couldn’t leave the book until I had finished it. Aklthough I had an important exam the next day, I spent my night with the protagonist Khalil, and sympathized with him, and tried to see the world through his eyes.

“I loved the way Hoda Barakat revealed her protagonist gradually, just as I loved the images of Beirut at the center of the craziness of the game of war, and I saw in the Beirut of the Stone of Laughter any city in a similar situation.

“Even now, I still appreciate The Stone of Laughter and see it as one of Hoda Barakat’s strongest works.”

17) Stone of Laughter, by Hoda Barakat, trans. Sophie Bennett (1990). The Lebanese Civil War sent an earthquake through Lebanese literature, and its effects are still being written and felt. Hoda Barakat’s novels have been at the center of this movement, and Stone of Laughter is one of her key works. When asked to recommend other Arab women writers, novelist Mansoura Ezz Eldin, and she said: “The novel that I’ve loved the most by an Arab woman writer is Hoda Barakat’s Stone of Laughter, which I read for the first time when the Egyptian edition was issued in 1998, and this was the first time I knew her writing. I bought it during the last two years of exams during university from a newspaper-and-bookseller who stood in front of the University of Cairo’s main gate, after its cover grabbed my attention.

“I read the first pages and couldn’t leave the book until I had finished it. Aklthough I had an important exam the next day, I spent my night with the protagonist Khalil, and sympathized with him, and tried to see the world through his eyes.

“I loved the way Hoda Barakat revealed her protagonist gradually, just as I loved the images of Beirut at the center of the craziness of the game of war, and I saw in the Beirut of the Stone of Laughter any city in a similar situation.

“Even now, I still appreciate The Stone of Laughter and see it as one of Hoda Barakat’s strongest works.”

18) Tiller of Waters, by Hoda Barakat, trans. Marilyn Booth (2001). Tiller of Waters made publisher Neil Hewison’s “5 to Read Before You Die” list. After Mitri’s apartment is taken over by refugees during Beirut’s protracted civil war, he re-visits the family’s old cloth shop, which is in a bombed-out, looted no-man’s land, and which he’d thought was completely destroyed. But down below, in the basement, everything is locked up and intact.

18) Tiller of Waters, by Hoda Barakat, trans. Marilyn Booth (2001). Tiller of Waters made publisher Neil Hewison’s “5 to Read Before You Die” list. After Mitri’s apartment is taken over by refugees during Beirut’s protracted civil war, he re-visits the family’s old cloth shop, which is in a bombed-out, looted no-man’s land, and which he’d thought was completely destroyed. But down below, in the basement, everything is locked up and intact.

19) Disciples of Passion, Hoda Barakat, trans. Marilyn Booth (1993). Hoda Barakat, a finalist for the Man Booker International in its final year as a prize for a writer’s whole oeuvre, has published relatively few novels, and you can’t go wrong with any of them. In this book, an unnamed Christian narrator tries to remember his relationship with a Muslim woman during Lebanon’s civil war.

Barakat’s most recent novel is unfortunately untranslated. See 10 Books by Arab Women Writers That Should Be Translated.

19) Disciples of Passion, Hoda Barakat, trans. Marilyn Booth (1993). Hoda Barakat, a finalist for the Man Booker International in its final year as a prize for a writer’s whole oeuvre, has published relatively few novels, and you can’t go wrong with any of them. In this book, an unnamed Christian narrator tries to remember his relationship with a Muslim woman during Lebanon’s civil war.

Barakat’s most recent novel is unfortunately untranslated. See 10 Books by Arab Women Writers That Should Be Translated.

20) Absent, by Betool Khedairi, trans. Muhayman Jamil (2005). I once had a torrid love affair with this book, which takes us from a vibrant and beautiful mosaic of Baghdad, shatters it into a thousand-thousand pieces, and moves us toward the present. The book centers on Dalal, a young woman living in a crowded Baghdad apartment with the childless aunt and uncle who raised her.

20) Absent, by Betool Khedairi, trans. Muhayman Jamil (2005). I once had a torrid love affair with this book, which takes us from a vibrant and beautiful mosaic of Baghdad, shatters it into a thousand-thousand pieces, and moves us toward the present. The book centers on Dalal, a young woman living in a crowded Baghdad apartment with the childless aunt and uncle who raised her.

21) The Story of Zahra, by Hanan al-Shaykh, trans Peter Ford (1994). The Story of Zahra is another novel of Lebanon’s civil war. This is a book Iraqi novelist Sinan Antoon chose for his “5 to Read Before You Die” list; a coming-of-age story set during Lebanon’s 1975-1990 war where Zahra is torn between strict father, dallying mother, and her own lover. It was also named by the Arab Writers Union as one of the Top 105 books of the 21st century.

More of al-Shaykh’s novels I devoured as a teenager that are less clear in my mind except that I loved them:

(22) Women of Sand and Myrrh, Hanan al-Shaykh, trans. Catherine Cobham (1992).

(23) Beirut Blues, Hanan al-Shaykh, trans. Catherine Cobham (1995).

21) The Story of Zahra, by Hanan al-Shaykh, trans Peter Ford (1994). The Story of Zahra is another novel of Lebanon’s civil war. This is a book Iraqi novelist Sinan Antoon chose for his “5 to Read Before You Die” list; a coming-of-age story set during Lebanon’s 1975-1990 war where Zahra is torn between strict father, dallying mother, and her own lover. It was also named by the Arab Writers Union as one of the Top 105 books of the 21st century.

More of al-Shaykh’s novels I devoured as a teenager that are less clear in my mind except that I loved them:

(22) Women of Sand and Myrrh, Hanan al-Shaykh, trans. Catherine Cobham (1992).

(23) Beirut Blues, Hanan al-Shaykh, trans. Catherine Cobham (1995).

24) Distant View of a Minaret, by Alifa Rifaat, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (1983). This slight short-story collection is Rifaat’s only literary production gathered together into a book. It was probably their mention by Chinua Achebe, more than anything else, that elevated Rifaat’s stories to a devoted following. But the stories — in a straightforward, realist style — hold up for their depiction of emotion through time nad place. The collection also makes translator Shakir Mustafa’s “5 to Read Before You Die” list.

24) Distant View of a Minaret, by Alifa Rifaat, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (1983). This slight short-story collection is Rifaat’s only literary production gathered together into a book. It was probably their mention by Chinua Achebe, more than anything else, that elevated Rifaat’s stories to a devoted following. But the stories — in a straightforward, realist style — hold up for their depiction of emotion through time nad place. The collection also makes translator Shakir Mustafa’s “5 to Read Before You Die” list.

25) A Man from Bashmour, by Salwa Bakr, trans. Nancy Roberts (2007). This novel, picked as one of the top 105 of the 20th century by the Arab Writers Union, was set in Egypt in the ninth century CE, when an Arab, Muslim ruling class governs a country of mostly Coptic-speaking Christians. Budayr is dispatched to the marshlands after a peasant revolt. You can also read Bakr on “Women and Arabic Literature.”

25) A Man from Bashmour, by Salwa Bakr, trans. Nancy Roberts (2007). This novel, picked as one of the top 105 of the 20th century by the Arab Writers Union, was set in Egypt in the ninth century CE, when an Arab, Muslim ruling class governs a country of mostly Coptic-speaking Christians. Budayr is dispatched to the marshlands after a peasant revolt. You can also read Bakr on “Women and Arabic Literature.”

26) Napthalene, by Alia Mamdouh, trans. Peter Theroux (2005). Iman Humaydan, when asked which novel by an Arab woman writer she’d recommend, said that “Alia Mamdouh was my great discovery — her book al-Wala3. You cannot imagine how beautiful this book is.” That book is not in English, but The Loved Ones and Mamdouh’s acclaimed Napthalene — reputedly the first book by an Iraqi woman to be translated into English — have made the crossing. This novel is a lyrical telling of a strong-willed girl’s coming-of-age in 1950s Baghdad.

26) Napthalene, by Alia Mamdouh, trans. Peter Theroux (2005). Iman Humaydan, when asked which novel by an Arab woman writer she’d recommend, said that “Alia Mamdouh was my great discovery — her book al-Wala3. You cannot imagine how beautiful this book is.” That book is not in English, but The Loved Ones and Mamdouh’s acclaimed Napthalene — reputedly the first book by an Iraqi woman to be translated into English — have made the crossing. This novel is a lyrical telling of a strong-willed girl’s coming-of-age in 1950s Baghdad.

27) The Granada Trilogy, by Radwa Ashour, trans. William Granara (2003). This is another that made the Arab Writers Union’s “top 105” list for the 20th century. It’s set in southern Spain before the expulsion of the Arabs and Jews and follows the family of the bookbinder Abu Jaafar as they witness the rise of Christopher Columbus and his hangers-on.

27) The Granada Trilogy, by Radwa Ashour, trans. William Granara (2003). This is another that made the Arab Writers Union’s “top 105” list for the 20th century. It’s set in southern Spain before the expulsion of the Arabs and Jews and follows the family of the bookbinder Abu Jaafar as they witness the rise of Christopher Columbus and his hangers-on.

28) The Open Door, by Latifa al-Zayyat, trans. Marilyn Booth (2001). Published in 1960 in Arabic and also on the “top 105” list from the Arab Writers Union, this is one of the few books published by women in the 1960s and 1970s that was turned into a film. Contemporary Egyptian women writers give the book mixed reviews, with a preference for al-Zayyat’s nonfiction, but it was doubtless a pioneering work, not least for its use of coloquial language. Back in 2001 when the English was released, Kirkus had a funny review urging “Oprah’s people” to have a look at it.

28) The Open Door, by Latifa al-Zayyat, trans. Marilyn Booth (2001). Published in 1960 in Arabic and also on the “top 105” list from the Arab Writers Union, this is one of the few books published by women in the 1960s and 1970s that was turned into a film. Contemporary Egyptian women writers give the book mixed reviews, with a preference for al-Zayyat’s nonfiction, but it was doubtless a pioneering work, not least for its use of coloquial language. Back in 2001 when the English was released, Kirkus had a funny review urging “Oprah’s people” to have a look at it.

29) The Last Chapter, by Leila Abouzeid, trans. Abouzeid and John Liechety (2000). For her “5 to read before you die” list, celebrated Moroccan author Laila Lalami chose Abouzeid’s Year of the Elephant, which is indeed her most celebrated work. But my fondness is for her semi-autobiographical The Last Chapter, a fresh and funny Moroccan coming-of-age.

29) The Last Chapter, by Leila Abouzeid, trans. Abouzeid and John Liechety (2000). For her “5 to read before you die” list, celebrated Moroccan author Laila Lalami chose Abouzeid’s Year of the Elephant, which is indeed her most celebrated work. But my fondness is for her semi-autobiographical The Last Chapter, a fresh and funny Moroccan coming-of-age.

30) Wild Mulberries, by Iman Humaydan, trans. Michelle Hartman (2008). Runner-up for the 2009 Banipal Prize, this book is still fondly spoken of by the great British writer Aamer Hussein, who was a prize judge that year. Judge Francine Stock wrote in her comments: “The translation never overstates, allowing the reader to see how the woman’s life is circumscribed by political and economic forces within her relationships with friends and family, so her father’s adherence to the silkworms that feed on the mulberry tree, for example, presages financial trouble. The detail here is all.”

30) Wild Mulberries, by Iman Humaydan, trans. Michelle Hartman (2008). Runner-up for the 2009 Banipal Prize, this book is still fondly spoken of by the great British writer Aamer Hussein, who was a prize judge that year. Judge Francine Stock wrote in her comments: “The translation never overstates, allowing the reader to see how the woman’s life is circumscribed by political and economic forces within her relationships with friends and family, so her father’s adherence to the silkworms that feed on the mulberry tree, for example, presages financial trouble. The detail here is all.”

31) Blue Aubergine, by Miral al-Tahawy, trans. Anthony Calderbank (2002). Blue Aubergine centers on Nada, a girl born prematurely in a traditional family — thus a “blue aubergine” of a baby — around the time of the 1967 naksa, or Egypt-Israeli war. The book’s three sections focus on Nada’s childhood, university years, and her gender-studies PhD, and they move between dream and reality. A novel that rewards the reader willing to follow.

Classic classics

31) Blue Aubergine, by Miral al-Tahawy, trans. Anthony Calderbank (2002). Blue Aubergine centers on Nada, a girl born prematurely in a traditional family — thus a “blue aubergine” of a baby — around the time of the 1967 naksa, or Egypt-Israeli war. The book’s three sections focus on Nada’s childhood, university years, and her gender-studies PhD, and they move between dream and reality. A novel that rewards the reader willing to follow.

Classic classics

32) The Principles of Sufism, by A’ishah al-Ba’uniyyah, ed. and trans. Th. Emil Homerin (2014). Al-Ba’uniyyah (d. 923 H/1517 AD) of Damascus was one of the great scholars in Islamic history and is perhaps the most prolific and prominent woman who wrote in Arabic prior to the modern period. You can also read a collection of al-Ba’uniyyah’s poetry, also trans. Th. Emil Homerin, Emanations of Grace. In Homerin’s words, “‘A’ishah is one of the very few women mystics in Islam who wrote and spoke for herself prior to the modern period. That gives us some important perspectives from the viewpoint of a woman on her society, on Islamic mysticism, and on Islam in general.”

Nonfiction

32) The Principles of Sufism, by A’ishah al-Ba’uniyyah, ed. and trans. Th. Emil Homerin (2014). Al-Ba’uniyyah (d. 923 H/1517 AD) of Damascus was one of the great scholars in Islamic history and is perhaps the most prolific and prominent woman who wrote in Arabic prior to the modern period. You can also read a collection of al-Ba’uniyyah’s poetry, also trans. Th. Emil Homerin, Emanations of Grace. In Homerin’s words, “‘A’ishah is one of the very few women mystics in Islam who wrote and spoke for herself prior to the modern period. That gives us some important perspectives from the viewpoint of a woman on her society, on Islamic mysticism, and on Islam in general.”

Nonfiction

33) A Woman in the Crossfire, by Samar Yazbek, trans. Max Weiss (2013). Raw, honest, terrifying, hopeful portrait of the first few months of uprising in Syria by one of its leading novelists. Yazbek, who is in the main a fiction and screenwriter, has now written two memoirs. This, the first one, takes us back to the hopeful and chaotic beginning of Syria’s now 19-month fight against the ruling regime.

33) A Woman in the Crossfire, by Samar Yazbek, trans. Max Weiss (2013). Raw, honest, terrifying, hopeful portrait of the first few months of uprising in Syria by one of its leading novelists. Yazbek, who is in the main a fiction and screenwriter, has now written two memoirs. This, the first one, takes us back to the hopeful and chaotic beginning of Syria’s now 19-month fight against the ruling regime.

34) The Crossing, by Samar Yazbek, trans. Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp and Nashwa Gowanlock (2015). The French translation of this book won the 2016 Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger, acclaimed as “not only edifying, but also with an overwhelming humanity and intelligence.” You can read an extract from The Crossing, the English translation, at The Guardian. It opens:

34) The Crossing, by Samar Yazbek, trans. Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp and Nashwa Gowanlock (2015). The French translation of this book won the 2016 Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger, acclaimed as “not only edifying, but also with an overwhelming humanity and intelligence.” You can read an extract from The Crossing, the English translation, at The Guardian. It opens:

The barbed wire lacerated my back. I was trembling uncontrollably. After long hours spent waiting for nightfall, to avoid attracting the attention of Turkish soldiers, I finally raised my head and gazed up at the distant sky, darkening to black. Under the wire fence marking the line of the border a tiny burrow had been dug out, just big enough for one person. My feet sank into the soil and the barbs mauled my back as I crawled across the line of separation between the two countries.

35) Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, by Nawal El Saadawi, trans. Marilyn Booth (1994). Although I do not rank El Saadawi’s fiction as her best work, I would be remiss in not including some of her nonfiction, where her voice is clear as she speaks directly about her experience as an activist and feminist. The great poet Iman Mersal recommends My Papers…My Life, which is unfortunately not in English translation.

Also: If you have a particular interest in El Saadawi, please go read the El Saadawi tribute-satire in Randa Jarrar’s short-story collection Him Me Muhammad Ali.

35) Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, by Nawal El Saadawi, trans. Marilyn Booth (1994). Although I do not rank El Saadawi’s fiction as her best work, I would be remiss in not including some of her nonfiction, where her voice is clear as she speaks directly about her experience as an activist and feminist. The great poet Iman Mersal recommends My Papers…My Life, which is unfortunately not in English translation.

Also: If you have a particular interest in El Saadawi, please go read the El Saadawi tribute-satire in Randa Jarrar’s short-story collection Him Me Muhammad Ali.

36) A Mountainous Journey: A Poet’s Autobiography, by Fadwa Tuqan, ed. Salma Khadra Jayyusi, trans. Olive E. Kenny. Tuqan, one of the top Palestinian poets of the twentieth century, was born in 1917, and writes her difficult journey from there to 1967. Tuqan remains an influential figure, and you can find Tuqan-related book swag at the art shop Watan.

36) A Mountainous Journey: A Poet’s Autobiography, by Fadwa Tuqan, ed. Salma Khadra Jayyusi, trans. Olive E. Kenny. Tuqan, one of the top Palestinian poets of the twentieth century, was born in 1917, and writes her difficult journey from there to 1967. Tuqan remains an influential figure, and you can find Tuqan-related book swag at the art shop Watan.

37) The Search: Personal Papers, by Latifa al-Zayyat, trans. by Sophie Bennett (1996). The great Egyptian poet Iman Mersal, when asked to recommend Arab women writers, said, “Likewise, there are memoirs written by some Arab female writers that deserve mention, even if one isn’t a fan of their work as a whole: Hamlat taftish: Awraq shakhsiya (1992), by Latifa Zayat, ِAwraqi…Hayati (1995), by Nawal El Saadawi, and Alaa al- Jisr (1986) by Aisha Abd al-Rahman (also known as Bint al-Shati). One feels, in these works, that the authors speak in their own voices, unfettered by the collective will or collective projects so present in their other writings.” More about al-Zayyat (1923-1996) at latifaalzayyat.net/.

Anthologies and short-story collections

37) The Search: Personal Papers, by Latifa al-Zayyat, trans. by Sophie Bennett (1996). The great Egyptian poet Iman Mersal, when asked to recommend Arab women writers, said, “Likewise, there are memoirs written by some Arab female writers that deserve mention, even if one isn’t a fan of their work as a whole: Hamlat taftish: Awraq shakhsiya (1992), by Latifa Zayat, ِAwraqi…Hayati (1995), by Nawal El Saadawi, and Alaa al- Jisr (1986) by Aisha Abd al-Rahman (also known as Bint al-Shati). One feels, in these works, that the authors speak in their own voices, unfettered by the collective will or collective projects so present in their other writings.” More about al-Zayyat (1923-1996) at latifaalzayyat.net/.

Anthologies and short-story collections

38) Final Night: Short Stories, by Buthaina Al Nasiri, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (2008). Al Nasiri’s stories have been written in a long exile — she has been living in Cairo since 1979 — and perhaps understandbale they don’t give a strong sense of place. The most memorable were “Circus Dog” and “Omar’s Hen,” and it was indeed the tenderness toward animal characters that brought the stories alive.

38) Final Night: Short Stories, by Buthaina Al Nasiri, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (2008). Al Nasiri’s stories have been written in a long exile — she has been living in Cairo since 1979 — and perhaps understandbale they don’t give a strong sense of place. The most memorable were “Circus Dog” and “Omar’s Hen,” and it was indeed the tenderness toward animal characters that brought the stories alive.

39) Stories by Egyptian Women: My Grandmother’s Cactus, ed. Marilyn Booth (1993). With stories by excellent short-form practitioners like Salwa Bakr as well as more poetic writers, like Ibtihal Salem. Unlike the collection Arab Women Writers: An Anthology of Short Stories, Booth’s considerations are primarily stylistic, literary, and voice-driven.

39) Stories by Egyptian Women: My Grandmother’s Cactus, ed. Marilyn Booth (1993). With stories by excellent short-form practitioners like Salwa Bakr as well as more poetic writers, like Ibtihal Salem. Unlike the collection Arab Women Writers: An Anthology of Short Stories, Booth’s considerations are primarily stylistic, literary, and voice-driven.

40) The Wiles of Men and Other Stories, by Salwa Bakr, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (1992). My favorites among these stories were those that foregrounded women who work as street peddlars, itinerant tea-sellers, and one woman who tilled the ground in an area near a roadside and grew corn. Women who are hemmed in on all sides and yet resilient. You can read one of Bakr’s short stories on Words Without Borders.

40) The Wiles of Men and Other Stories, by Salwa Bakr, trans. Denys Johnson-Davies (1992). My favorites among these stories were those that foregrounded women who work as street peddlars, itinerant tea-sellers, and one woman who tilled the ground in an area near a roadside and grew corn. Women who are hemmed in on all sides and yet resilient. You can read one of Bakr’s short stories on Words Without Borders.

41) The Square Moon: Supernatural Tales, by Ghada Samman, trans. Issa J. Boullata (1998). Winner of the Arkansas Arabic Translation Award, a collection of eerie, well-crafted tales by the loved-and-hated Samman, translated by the much-acclaimed Boullata. Includes “The Brain’s Closed Castle,’ a story of an adulterer’s ghost taking revenge on both lover and her husband.

Poetry

41) The Square Moon: Supernatural Tales, by Ghada Samman, trans. Issa J. Boullata (1998). Winner of the Arkansas Arabic Translation Award, a collection of eerie, well-crafted tales by the loved-and-hated Samman, translated by the much-acclaimed Boullata. Includes “The Brain’s Closed Castle,’ a story of an adulterer’s ghost taking revenge on both lover and her husband.

Poetry

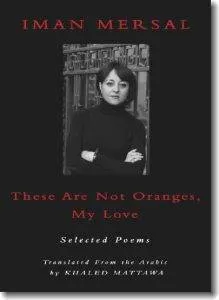

42) These Are Not Oranges, My Love, by Iman Mersal, trans. Khaled Mattawa (2008). Mersal is, by common approbation, one of the most interesting and thus “important” poets of her generation. I would most like to read Mersal’s Until I Give Up the Idea of Houses, which Robyn Creswell is currently translating into English, but it’s not yet ready. Poems from Oranges here. Also I once put together a “holiday gift” list of 10 poems by Mersal.

42) These Are Not Oranges, My Love, by Iman Mersal, trans. Khaled Mattawa (2008). Mersal is, by common approbation, one of the most interesting and thus “important” poets of her generation. I would most like to read Mersal’s Until I Give Up the Idea of Houses, which Robyn Creswell is currently translating into English, but it’s not yet ready. Poems from Oranges here. Also I once put together a “holiday gift” list of 10 poems by Mersal.

43) Hagar Before the Occupation, Hagar After the Occupation, by Amal al-Jubouri, trans. Rebecca Gayle Howell with Husam Qaisi (2011). This collection, by poet and activist al-Jubouri, puts poems side by side, such as “Religion Before the Occupation” and “Religion After the Occupation.” In 2012, this collection made the Best Translated Book Award shortlist.

43) Hagar Before the Occupation, Hagar After the Occupation, by Amal al-Jubouri, trans. Rebecca Gayle Howell with Husam Qaisi (2011). This collection, by poet and activist al-Jubouri, puts poems side by side, such as “Religion Before the Occupation” and “Religion After the Occupation.” In 2012, this collection made the Best Translated Book Award shortlist.

44) The War Works Hard, by Dunya Mikhail, trans. Elizabeth Winslow (2005). The comments of poet Etel Adnan are to the point: “Blunt as well as subtle, she makes of war a distinct entity, thus turning it into a myth. To her own question, ‘What does it mean to die all this death?,’ her poems answer that it means to reveal the only redeeming power that we have: the existence of love.” The title poem is a signature work about war; you can watch her discuss it at the Rotterdam Literature Festival in 2009.

44) The War Works Hard, by Dunya Mikhail, trans. Elizabeth Winslow (2005). The comments of poet Etel Adnan are to the point: “Blunt as well as subtle, she makes of war a distinct entity, thus turning it into a myth. To her own question, ‘What does it mean to die all this death?,’ her poems answer that it means to reveal the only redeeming power that we have: the existence of love.” The title poem is a signature work about war; you can watch her discuss it at the Rotterdam Literature Festival in 2009.

45) The Poetry of Arab Women: A Contemporary Anthology, ed. Nathalie Handal (2001). This collection could go under each of our subheads, as it brings together more than 200 poems by eighty-some poets who write in Arabic, French, English, and Swedish, and among them are startling, bright poetic voices: Etel Adnan, Andre Chedid, Fadwa Tuqan.

Note: There should be more books in this section, there are great omissions, such as Nazik Al-Malaika and Sania Saleh, neither of whom has a collected work in English.

For young readers

45) The Poetry of Arab Women: A Contemporary Anthology, ed. Nathalie Handal (2001). This collection could go under each of our subheads, as it brings together more than 200 poems by eighty-some poets who write in Arabic, French, English, and Swedish, and among them are startling, bright poetic voices: Etel Adnan, Andre Chedid, Fadwa Tuqan.

Note: There should be more books in this section, there are great omissions, such as Nazik Al-Malaika and Sania Saleh, neither of whom has a collected work in English.

For young readers

46) Code Name: Butterfly, by Ahlam Bsharat, trans. Nancy Roberts (2016). The novel’s protagonist, Butterfly, is trying to feel her way around life in contemporary Palestine. As I wrote in a review for The National, “Since this is a close first-person narrative, Butterfly’s uncertainties induce a vertiginous feeling in the reader. We look out through the eyes of a 14 or 15-year-old girl who doesn’t know what to think about her eyebrows, much less the two-state solution. We, like her, must start over with new vocabulary. Indeed, if Butterfly has a superpower, it’s her mastery of the power of questions.”

46) Code Name: Butterfly, by Ahlam Bsharat, trans. Nancy Roberts (2016). The novel’s protagonist, Butterfly, is trying to feel her way around life in contemporary Palestine. As I wrote in a review for The National, “Since this is a close first-person narrative, Butterfly’s uncertainties induce a vertiginous feeling in the reader. We look out through the eyes of a 14 or 15-year-old girl who doesn’t know what to think about her eyebrows, much less the two-state solution. We, like her, must start over with new vocabulary. Indeed, if Butterfly has a superpower, it’s her mastery of the power of questions.”

47) The Servant, by Fatima Sharafeddine, trans. the author (2013). My review of the book is based solely on the Arabic, but the clear, urgent langauge of the novel reaches directly into the reader’s chest and grabs their heart. The book follows a young girl who is sent by her family to work as a servant in big-city Beirut. What choices can she make to maintain herself and look forward to a life that’s more of her own design?

47) The Servant, by Fatima Sharafeddine, trans. the author (2013). My review of the book is based solely on the Arabic, but the clear, urgent langauge of the novel reaches directly into the reader’s chest and grabs their heart. The book follows a young girl who is sent by her family to work as a servant in big-city Beirut. What choices can she make to maintain herself and look forward to a life that’s more of her own design?

Translated from OTHER LANGUAGES

Recent novels 48) Seeing Red, by Lina Meruane, trans. from the Spanish Megan McDowell (2016). As I wrote in a review elsewhere: “Lina Meruane’s semi-autobiographical Seeing Red is full of rhythmical jolts. At times, the reader is thrown to the end of a sentence, where she unexpectedly stops and teeters there, waiting. Then the next sentence reaches out and draws the reader on, plunging her into the smells, sounds, and spatial imbalances of the worlds around our protagonist, sometimes in the New York City where the fictional and real Lina Meruanes both earned their PhDs, and sometimes in Santiago de Chile, where the fictional and real Lina Meruanes both have Arab-Chilean families.”

48) Seeing Red, by Lina Meruane, trans. from the Spanish Megan McDowell (2016). As I wrote in a review elsewhere: “Lina Meruane’s semi-autobiographical Seeing Red is full of rhythmical jolts. At times, the reader is thrown to the end of a sentence, where she unexpectedly stops and teeters there, waiting. Then the next sentence reaches out and draws the reader on, plunging her into the smells, sounds, and spatial imbalances of the worlds around our protagonist, sometimes in the New York City where the fictional and real Lina Meruanes both earned their PhDs, and sometimes in Santiago de Chile, where the fictional and real Lina Meruanes both have Arab-Chilean families.”

49) Kite, by Dominique Eddé, trans. from the French Ros Schwartz (2012). Longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award in 2013, Kite begins in the 1960s and ending in the late ’80s. It follows the passionate relationship of Mali and Farid and the changes in Egyptian and Lebanese upper and middle-class life. You can read an excerpt of the book’s dense, shifting prose on Asymptote.

49) Kite, by Dominique Eddé, trans. from the French Ros Schwartz (2012). Longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award in 2013, Kite begins in the 1960s and ending in the late ’80s. It follows the passionate relationship of Mali and Farid and the changes in Egyptian and Lebanese upper and middle-class life. You can read an excerpt of the book’s dense, shifting prose on Asymptote.

50) The Sexual Life of an Islamist in Paris, by Leila Marouane, trans. from the French Alison Anderson (2010). This wonderfully bizarre novel follows “Basile Tocquard,” a handsome, wealthy, Parisian bank manager who was born in Algeria and was once devout. His story is all filtered through an unsympathetic female narrator. It’s unclear: Is the liberated Ben Mokhtar/Tocquard finding himself? Or is he creating himself (being created) from the books of Loubna Minbar, a fictional Algerian novelist who “steals people’s lives”?

The novel: Modern classics

50) The Sexual Life of an Islamist in Paris, by Leila Marouane, trans. from the French Alison Anderson (2010). This wonderfully bizarre novel follows “Basile Tocquard,” a handsome, wealthy, Parisian bank manager who was born in Algeria and was once devout. His story is all filtered through an unsympathetic female narrator. It’s unclear: Is the liberated Ben Mokhtar/Tocquard finding himself? Or is he creating himself (being created) from the books of Loubna Minbar, a fictional Algerian novelist who “steals people’s lives”?

The novel: Modern classics

51) Kiffe Kiffe Tomorrow, by Faïza Guène, trans. from the French Sarah Adams (2006). I know what you’re thinking: What? Kiffe Kiffe Tomorrow a modern classic? But this enormous bestseller, which follows Doria, a 15-year-old Moroccan girl living in a housing project outside Paris, and was written by Guene when she was still a teen, is not just a fun read, but marked a shift in French literature by its Moroccan and Algerian citizens.

51) Kiffe Kiffe Tomorrow, by Faïza Guène, trans. from the French Sarah Adams (2006). I know what you’re thinking: What? Kiffe Kiffe Tomorrow a modern classic? But this enormous bestseller, which follows Doria, a 15-year-old Moroccan girl living in a housing project outside Paris, and was written by Guene when she was still a teen, is not just a fun read, but marked a shift in French literature by its Moroccan and Algerian citizens.

52) The Abductor, by Leila Marouane, trans. from the French Felicity McNab (2001). In this tragi-comedic farce, a favorite mode of Marouane’s a a woman has been repudiated three times by her husband (of many years and six daughters) and thereby, under a strict Islam, the clownish man has divorced her. He regrets it, but is told his wife must marry and divorce someone else to be able to remarry him.

52) The Abductor, by Leila Marouane, trans. from the French Felicity McNab (2001). In this tragi-comedic farce, a favorite mode of Marouane’s a a woman has been repudiated three times by her husband (of many years and six daughters) and thereby, under a strict Islam, the clownish man has divorced her. He regrets it, but is told his wife must marry and divorce someone else to be able to remarry him.

53) Fantasia: An Algerian Cavalcade, by Assia Djebar, trans. Dorothy S. Blair. Djebar, who made the “5 Arabic books to read before you die” list despite not writing in Arabic, was frequently mentioned for the Nobel Prize for Literature and took plenty of other prizes, including the Neustadt and being the first from North Africa elected to the Académie française. Weaving together a coming-of-age and the invasion of Algeria, passionate personal desires and dispassionate historical documents, it is a tour de force.

53) Fantasia: An Algerian Cavalcade, by Assia Djebar, trans. Dorothy S. Blair. Djebar, who made the “5 Arabic books to read before you die” list despite not writing in Arabic, was frequently mentioned for the Nobel Prize for Literature and took plenty of other prizes, including the Neustadt and being the first from North Africa elected to the Académie française. Weaving together a coming-of-age and the invasion of Algeria, passionate personal desires and dispassionate historical documents, it is a tour de force.

54) Sitt Marie Rose, by Etel Adnan, trans. from the French Georgina Kleege (1982). Born in 1925, Etel Adnan has finally come into the spotlight for her artwork (or “visual poems“), which recently featured at the Serpentine Galleries in London. Her poetry also gets steady attention in certain quarters, written in English or translated from the French.

But her 1978 novel remains seminal. It was published first in Arabic translation, in 1977, and was set before and during Lebanon’s civil war. It’s based on the story of a woman kidnapped, later murdered, by the Christian Phalangists for her support of Palestinians. Many still consider it Lebanon’s defining civil-war novel.

Nonfiction

54) Sitt Marie Rose, by Etel Adnan, trans. from the French Georgina Kleege (1982). Born in 1925, Etel Adnan has finally come into the spotlight for her artwork (or “visual poems“), which recently featured at the Serpentine Galleries in London. Her poetry also gets steady attention in certain quarters, written in English or translated from the French.

But her 1978 novel remains seminal. It was published first in Arabic translation, in 1977, and was set before and during Lebanon’s civil war. It’s based on the story of a woman kidnapped, later murdered, by the Christian Phalangists for her support of Palestinians. Many still consider it Lebanon’s defining civil-war novel.

Nonfiction

55) Algerian White, by Assia Djebar, trans. from the French David Kelley (2010). In this complex, interwoven text, Djebar pulls together conversations remembered and imagioned between herself and her literary peers and predecessors. They include author Albert Camus; psychiatrist Mahfoud Boucebi; sociologist M’Hamed Boukhobza; playwright Abdelkader Alloula.

Short-story collections

55) Algerian White, by Assia Djebar, trans. from the French David Kelley (2010). In this complex, interwoven text, Djebar pulls together conversations remembered and imagioned between herself and her literary peers and predecessors. They include author Albert Camus; psychiatrist Mahfoud Boucebi; sociologist M’Hamed Boukhobza; playwright Abdelkader Alloula.

Short-story collections

56) Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, by Assia Djebar, trans. from the French Marjolijn de Jager (1992). This book, in its English translation, won a ALTA Outstanding Translation of the Year prize. As with much of Djebar’s work, the works in this collection address the liberty or cloistering of women, the writing of history, and the relationship of language and oppression. If you want one introduction to Djebar’s work, this is it.

Graphic novels

56) Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, by Assia Djebar, trans. from the French Marjolijn de Jager (1992). This book, in its English translation, won a ALTA Outstanding Translation of the Year prize. As with much of Djebar’s work, the works in this collection address the liberty or cloistering of women, the writing of history, and the relationship of language and oppression. If you want one introduction to Djebar’s work, this is it.

Graphic novels

57) Bye-bye Babylon, by Lamia Ziade, trans. from French Olivia Snaije (2012). This wonderfully pop-art, gaudily colorful illustrated novel of Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war contasts consumerist “paradise” with the parallel consumerist and consuming civil war. Outrageous, genre-bending, and an important take on war.

Poetry

57) Bye-bye Babylon, by Lamia Ziade, trans. from French Olivia Snaije (2012). This wonderfully pop-art, gaudily colorful illustrated novel of Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war contasts consumerist “paradise” with the parallel consumerist and consuming civil war. Outrageous, genre-bending, and an important take on war.

Poetry

58) She Says, by Venus Khoury-Ghata, trans. from the French Marilyn Hacker (2003). Khoury-Ghata is winner of a host of French poetry prizes, including the Prix Goncourt for her entire ouevre in 2011. Hacker is also an award-winning poet and translator. From the collection:

She says

the earth is so vast one can’t help but be lost like water from a broken jug/

There is no fortress against the wind

the winter wanderer must count on the compassion of walls

Also:

59) Here There Was Once a Country, by Venus Khoury-Ghata, trans. from the French Marilyn Hacker (2001).

60) Nettles: Poems, by Venus Khoury-Ghata, trans. from the French Marilyn Hacker (2008).

58) She Says, by Venus Khoury-Ghata, trans. from the French Marilyn Hacker (2003). Khoury-Ghata is winner of a host of French poetry prizes, including the Prix Goncourt for her entire ouevre in 2011. Hacker is also an award-winning poet and translator. From the collection:

She says

the earth is so vast one can’t help but be lost like water from a broken jug/

There is no fortress against the wind

the winter wanderer must count on the compassion of walls

Also:

59) Here There Was Once a Country, by Venus Khoury-Ghata, trans. from the French Marilyn Hacker (2001).

60) Nettles: Poems, by Venus Khoury-Ghata, trans. from the French Marilyn Hacker (2008).

61) The Arab Apocalypse, by Etel Adnan, trans. from the French Etel Adnan (1988). Boom. Adnan began writing The Arab Apocalypse in January 1975 in Beirut, months before the start of the war. It is a work of great visual and literary craft, and if you’re in London, you can see the typescript of the book displayed along with some of Adnan’s visual art.

For Young Readers

61) The Arab Apocalypse, by Etel Adnan, trans. from the French Etel Adnan (1988). Boom. Adnan began writing The Arab Apocalypse in January 1975 in Beirut, months before the start of the war. It is a work of great visual and literary craft, and if you’re in London, you can see the typescript of the book displayed along with some of Adnan’s visual art.

For Young Readers

62) A Game for Swallows, by Zeina Abirached, trans. from the French Edward Gauvin (2012). At my house, this story of children during the Lebanese civil war, charmingly drawn by Abirached, was read so many times, by so many different-sized hands, that it fell apart. When Zeina was born, the Lebanese civil war was already six years old, for her it’s just the way things are. Yet the book never for a moment loses its humanity. A Young Adult Library Services Association “Great Graphic Novels” pick.

Also:

63) I Remember Beirut, by Zeina Abirached, trans. from the French Edward Gauvin (2014).

62) A Game for Swallows, by Zeina Abirached, trans. from the French Edward Gauvin (2012). At my house, this story of children during the Lebanese civil war, charmingly drawn by Abirached, was read so many times, by so many different-sized hands, that it fell apart. When Zeina was born, the Lebanese civil war was already six years old, for her it’s just the way things are. Yet the book never for a moment loses its humanity. A Young Adult Library Services Association “Great Graphic Novels” pick.

Also:

63) I Remember Beirut, by Zeina Abirached, trans. from the French Edward Gauvin (2014).

Written in English

Recent novels 64) The Moor’s Account, by Laila Lalami (2014). This, Lalami’s second novel, was a Pulitzer finalist and won the American Book Award, Arab-American Book Award, and others. It is a fictional memoir of the Moroccan slave often written of as the “first black explorer of America,” described by Cabeza de Vaca as “an Arab Negro from Azamor.”

Sofia Samatar is Somali-American but she has a specialization in Arabic literature, so I want you to read her A Stranger in Olondria (2013), thanks.

The novel: Modern classics

64) The Moor’s Account, by Laila Lalami (2014). This, Lalami’s second novel, was a Pulitzer finalist and won the American Book Award, Arab-American Book Award, and others. It is a fictional memoir of the Moroccan slave often written of as the “first black explorer of America,” described by Cabeza de Vaca as “an Arab Negro from Azamor.”

Sofia Samatar is Somali-American but she has a specialization in Arabic literature, so I want you to read her A Stranger in Olondria (2013), thanks.

The novel: Modern classics

65) Map of Home, by Randa Jarrar (2008). This classic of the Arab-American-coming-of-age genre tells Nidali’s Palestinian-Egyptian-American story as she moves between Kuwait, Egypt, and the US, set among the conflicting political framings of the Gulf War I and Palestine-Israel. But what makes Jarrar’s work swing is her voice and her sense of humor.

65) Map of Home, by Randa Jarrar (2008). This classic of the Arab-American-coming-of-age genre tells Nidali’s Palestinian-Egyptian-American story as she moves between Kuwait, Egypt, and the US, set among the conflicting political framings of the Gulf War I and Palestine-Israel. But what makes Jarrar’s work swing is her voice and her sense of humor.

66) Arabian Jazz, by Diana Abu Jaber (2003). This novel, Abu-Jaber’s debut, won the Oregon Book Award and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway. It’s set in an impoverished, rural, largely white community in upstate New York where Jordanian Matussem Ramoud, along with his identity-stricken daughter Jemorah and other members of his family, move in.

66) Arabian Jazz, by Diana Abu Jaber (2003). This novel, Abu-Jaber’s debut, won the Oregon Book Award and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway. It’s set in an impoverished, rural, largely white community in upstate New York where Jordanian Matussem Ramoud, along with his identity-stricken daughter Jemorah and other members of his family, move in.

67) The Translator, by Leila Aboulela (1999). The Translator, Aboulela’s debut, is a story about a young Muslim Sudanese widow living in Scotland and her blooming relationship with a secular Scottish Middle Eastern scholar. It was shortlisted for the Saltire Society Scottish First Book of the Year Award and the Race and Media Award, nominated for the Orange, and chosen as a Notable Book of the Year by the NYT in 2006.

67) The Translator, by Leila Aboulela (1999). The Translator, Aboulela’s debut, is a story about a young Muslim Sudanese widow living in Scotland and her blooming relationship with a secular Scottish Middle Eastern scholar. It was shortlisted for the Saltire Society Scottish First Book of the Year Award and the Race and Media Award, nominated for the Orange, and chosen as a Notable Book of the Year by the NYT in 2006.

68) The Last Life, by Claire Messud (1999). Perhaps Messud’s strongest novel, The Last Life is the portrait of the disintegration of a French-Algerian family that fled Algiers for France in the 1950s.

It’s a coming-of-age but also a Djebarian meditation on the creation of private and shared histories.

68) The Last Life, by Claire Messud (1999). Perhaps Messud’s strongest novel, The Last Life is the portrait of the disintegration of a French-Algerian family that fled Algiers for France in the 1950s.

It’s a coming-of-age but also a Djebarian meditation on the creation of private and shared histories.

69) The Map of Love, by Ahdaf Soueif (1998). Shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1999, The Map of Love is a historical account of British imperialism and Egyptian nationalism through the love story of Anna Winterbourne and Sharif al-Baroudi, told through the voice of Sharif’s grandniece, Amal.

Also:

70) In the Eye of the Sun, by Ahdaf Soueif (1992).

Short-story collections

69) The Map of Love, by Ahdaf Soueif (1998). Shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1999, The Map of Love is a historical account of British imperialism and Egyptian nationalism through the love story of Anna Winterbourne and Sharif al-Baroudi, told through the voice of Sharif’s grandniece, Amal.

Also:

70) In the Eye of the Sun, by Ahdaf Soueif (1992).

Short-story collections

71) Him, Me, Muhammad Ali, Randa Jarrar (2016). In the best Jarrarian style, these stories wrap around the world: Cairo, Alexandria, Gaza, Detroit, New York City, Istanbul, and beyond. As I wrote elsewhere:

These pluralities rarely feel strained, and they’re never the sort of Friedman-esque stock characters that exist to make a point about “globalization.” They go to the heart of Jarrar’s landscapes, which are divided by class, gender, sexuality, and privilege, but are never wholly separate. The collection links together the rich and middle-class and poor, urban and rural, Global North and Global South, black and Arab and white.

Plus, who doesn’t sometimes feel like a bisexual half Transjordanian ibex in a tiny Texas town: a huge and shaggy misfit in a very strange land?

71) Him, Me, Muhammad Ali, Randa Jarrar (2016). In the best Jarrarian style, these stories wrap around the world: Cairo, Alexandria, Gaza, Detroit, New York City, Istanbul, and beyond. As I wrote elsewhere:

These pluralities rarely feel strained, and they’re never the sort of Friedman-esque stock characters that exist to make a point about “globalization.” They go to the heart of Jarrar’s landscapes, which are divided by class, gender, sexuality, and privilege, but are never wholly separate. The collection links together the rich and middle-class and poor, urban and rural, Global North and Global South, black and Arab and white.

Plus, who doesn’t sometimes feel like a bisexual half Transjordanian ibex in a tiny Texas town: a huge and shaggy misfit in a very strange land?

72) In a Curious Land: Stories from Home, by Susan Muaddi Darraj (2015). Winner of the Gracey Paley Prize in Short Fiction and the Arab American Book Award, these warm, interlinked short stories follow inhabitants of and in the Palestinian village of Tel al-Hilou, moving from Ottoman times to the present day. You can read a brief excerpt on the publisher’s website.

Nonfiction books by Arab women

72) In a Curious Land: Stories from Home, by Susan Muaddi Darraj (2015). Winner of the Gracey Paley Prize in Short Fiction and the Arab American Book Award, these warm, interlinked short stories follow inhabitants of and in the Palestinian village of Tel al-Hilou, moving from Ottoman times to the present day. You can read a brief excerpt on the publisher’s website.

Nonfiction books by Arab women

73) Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, by Lila Abu-Lughod (2013). Perhaps this work is more scholarly than creative, but it’s also excellent storytelling, and storytelling about storytelling, taking apart narratives that fall into the very popular genre of “Saving Muslim Women” stories. So while you’re reading Arab women, you can also read this book that takes apart the frame in which Arab and Muslim women are often placed.

73) Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, by Lila Abu-Lughod (2013). Perhaps this work is more scholarly than creative, but it’s also excellent storytelling, and storytelling about storytelling, taking apart narratives that fall into the very popular genre of “Saving Muslim Women” stories. So while you’re reading Arab women, you can also read this book that takes apart the frame in which Arab and Muslim women are often placed.

74) Nothing to Lose But Your Life, by Suad Amiry (2010). In this wonderfully warm and funny work of adventure journalsim, Amiry crosses the border into Israel illegally with other Palestinian workers seeking day employment on the other side. Although there are moments of danger, it’s told with Amiry’s characteristic risk-averse humor, which she brings into all her writing and public speaking.

Also:

75) Sharon and My Mother-in-law, by Suad Amiry (2003).

74) Nothing to Lose But Your Life, by Suad Amiry (2010). In this wonderfully warm and funny work of adventure journalsim, Amiry crosses the border into Israel illegally with other Palestinian workers seeking day employment on the other side. Although there are moments of danger, it’s told with Amiry’s characteristic risk-averse humor, which she brings into all her writing and public speaking.

Also:

75) Sharon and My Mother-in-law, by Suad Amiry (2003).

76) The Girl Who Fell to Earth, by Sophia al-Maria (2012). One of a handful of fresh new West-to-East coming-of-age stories, The Girl Who Fell to Earth is both moving and funny, as well as illuminating about small-town America and changing realities in Qatar. You can read a web sampler at Harper Collins.

76) The Girl Who Fell to Earth, by Sophia al-Maria (2012). One of a handful of fresh new West-to-East coming-of-age stories, The Girl Who Fell to Earth is both moving and funny, as well as illuminating about small-town America and changing realities in Qatar. You can read a web sampler at Harper Collins.

77) Beirut Fragments, Jean Said Makdisi (1990). This quote from a 1990 review in the LATimes not only gets the book, but is something we really should’ve tattooed on our bodies somewhere: “The greatest accomplishment of this profound, heartbreaking book is that, through Makdisi’s eyes, it is possible to rid one’s mind of all the cant and rubbish that has been spoken about Beirut, and to see what has happened to that city not as a nightmare, with all the connotations of otherness and unreality which that world implies, but as a terrible human possibility.”

77) Beirut Fragments, Jean Said Makdisi (1990). This quote from a 1990 review in the LATimes not only gets the book, but is something we really should’ve tattooed on our bodies somewhere: “The greatest accomplishment of this profound, heartbreaking book is that, through Makdisi’s eyes, it is possible to rid one’s mind of all the cant and rubbish that has been spoken about Beirut, and to see what has happened to that city not as a nightmare, with all the connotations of otherness and unreality which that world implies, but as a terrible human possibility.”

78) A Border Passage: From Cairo to America-A Woman’s Journey, by Leila Ahmed (1999). There are criticisms to be made of Ahmed’s positioning of Islam, and who can know Islam (and how), but there are indisputibly beautiful descriptions of her girlhood Cairo. Read an excerpt, which begins: “It was as if there were to life itself a quality of music in that time, the era of my childhood, and in that place, the remote edge of Cairo. There the city petered out into a scattering of villas leading into tranquil country fields. On the other side of our house was the profound, unsurpassable quiet of the desert.”

Poetry

78) A Border Passage: From Cairo to America-A Woman’s Journey, by Leila Ahmed (1999). There are criticisms to be made of Ahmed’s positioning of Islam, and who can know Islam (and how), but there are indisputibly beautiful descriptions of her girlhood Cairo. Read an excerpt, which begins: “It was as if there were to life itself a quality of music in that time, the era of my childhood, and in that place, the remote edge of Cairo. There the city petered out into a scattering of villas leading into tranquil country fields. On the other side of our house was the profound, unsurpassable quiet of the desert.”

Poetry

79) 3arabi Song, Zeina Hashem Beck (2016). 3arabi Song won the 2016 Rattle Chapbook Prize, selected from among 1720 entries. When the book first came out this September, her publisher sent me this impassionaed message: “Zeina is just an amazing poet; I don’t know how else to say it. Having worked in publishing for almost two decades, I’ve never felt more sure that a writer was on the cusp of fame. She’s only 35, with a few books under her belt, but I think she’ll be a household name in literature some day. Just this year she’s won our prize from almost 2,000 manuscript entries, the May Sarton Prize from another press, and had yet a third book selected for an award by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate of the UK). Being so gifted, she serves as a powerful and necessary bridge between cultures.” You can read some of her work online.

79) 3arabi Song, Zeina Hashem Beck (2016). 3arabi Song won the 2016 Rattle Chapbook Prize, selected from among 1720 entries. When the book first came out this September, her publisher sent me this impassionaed message: “Zeina is just an amazing poet; I don’t know how else to say it. Having worked in publishing for almost two decades, I’ve never felt more sure that a writer was on the cusp of fame. She’s only 35, with a few books under her belt, but I think she’ll be a household name in literature some day. Just this year she’s won our prize from almost 2,000 manuscript entries, the May Sarton Prize from another press, and had yet a third book selected for an award by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate of the UK). Being so gifted, she serves as a powerful and necessary bridge between cultures.” You can read some of her work online.

80) 50 Water Dreams, by Siwar Masannat (2015). This is the auspicious debut of Jordanian writer and 7iber alum Siwar Massannat, winner of the Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s First Book Award. I’ll quote poet Ilya Kaminsky: “”How rare and exhilarating it is, in our time, to find a book that is both wildly inventive and daring in its style and incredibly compelling in its content! 50 WATER DREAMS takes us on a book-long journey of Fadia and Ishmael and a mysterious horse that keeps the house company (‘horse that humanizes the house,’ ‘horse that may keep the house from dying’). The romance here is this: Fadia’s father was a dead man forced to go home on foot & Ishmael’s mother exiled. What happens in this book? Cruelty and passion and heartbreak become a myth for our times of conflict. How lucky we are to find a poetry debut that isn’t afraid of ideas, of mysteries, of politics, of passion. How brave she is to say ‘I saw nobody coming so I went instead.’ And to dare us: ‘I want to put you in my revolution.’ Like Zbigniew Herbert, this poet wants ‘to hide you in my eyelids & the nation,’ like Venus Khoury-Ghata, she makes a mythological pastoral, a book of voices that speak for more than one person.”

80) 50 Water Dreams, by Siwar Masannat (2015). This is the auspicious debut of Jordanian writer and 7iber alum Siwar Massannat, winner of the Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s First Book Award. I’ll quote poet Ilya Kaminsky: “”How rare and exhilarating it is, in our time, to find a book that is both wildly inventive and daring in its style and incredibly compelling in its content! 50 WATER DREAMS takes us on a book-long journey of Fadia and Ishmael and a mysterious horse that keeps the house company (‘horse that humanizes the house,’ ‘horse that may keep the house from dying’). The romance here is this: Fadia’s father was a dead man forced to go home on foot & Ishmael’s mother exiled. What happens in this book? Cruelty and passion and heartbreak become a myth for our times of conflict. How lucky we are to find a poetry debut that isn’t afraid of ideas, of mysteries, of politics, of passion. How brave she is to say ‘I saw nobody coming so I went instead.’ And to dare us: ‘I want to put you in my revolution.’ Like Zbigniew Herbert, this poet wants ‘to hide you in my eyelids & the nation,’ like Venus Khoury-Ghata, she makes a mythological pastoral, a book of voices that speak for more than one person.”

81) Poet in Andalucia, by Nathalie Handal (2012). I’m fairly certain this is my favorite Nathalie Handal collection. As I wrote about this collection in a 2012 review, “Handal is particularly drawn to the shadows of Andalucía’s joint Islamic, Judaic, and Christian history. In “Alhandal y las Murallas de Córdoba,” “The past is here / the song of the Arabs here, / the song of the Jews, / the Romans, / the Spaniards, / and the phantoms.” It is clear why: Palestine is not mentioned, but it is everywhere. Palestine is in Murcia, in Toledo, in Córdoba, and in a dozen other places. The narrator of “The Thing about Feathers” does not name a country, but it is hard not to see Palestine: “I am seven / it is the day before our departure, / the day my father / gives me a notebook, / and I tell him, / this is where I’ll keep my country.”

Also:

82) Love and Strange Horses, by Nathalie Handal (2010).

81) Poet in Andalucia, by Nathalie Handal (2012). I’m fairly certain this is my favorite Nathalie Handal collection. As I wrote about this collection in a 2012 review, “Handal is particularly drawn to the shadows of Andalucía’s joint Islamic, Judaic, and Christian history. In “Alhandal y las Murallas de Córdoba,” “The past is here / the song of the Arabs here, / the song of the Jews, / the Romans, / the Spaniards, / and the phantoms.” It is clear why: Palestine is not mentioned, but it is everywhere. Palestine is in Murcia, in Toledo, in Córdoba, and in a dozen other places. The narrator of “The Thing about Feathers” does not name a country, but it is hard not to see Palestine: “I am seven / it is the day before our departure, / the day my father / gives me a notebook, / and I tell him, / this is where I’ll keep my country.”

Also:

82) Love and Strange Horses, by Nathalie Handal (2010).

83) Sea and Fog, by Etel Adnan (2012). Winner of the 2013 LAMBDA Literary Award for Poetry and the 2013 California Book Award for Poetry this is meditative as it is dark and pulsing. We published a section of it in the Feb. 2014 issue of Missing Slate: “Time is my country, fog is my land.”

Also:

84) Seasons, by Etel Adnan (2008).

85) In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, by Etel Adnan (2005).

86) In/somnia, by Etel Adnan (2002).

87) There: In the Light and the Darkness of the Self and the Other, by Etel Adnan (1997).

83) Sea and Fog, by Etel Adnan (2012). Winner of the 2013 LAMBDA Literary Award for Poetry and the 2013 California Book Award for Poetry this is meditative as it is dark and pulsing. We published a section of it in the Feb. 2014 issue of Missing Slate: “Time is my country, fog is my land.”

Also:

84) Seasons, by Etel Adnan (2008).

85) In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, by Etel Adnan (2005).

86) In/somnia, by Etel Adnan (2002).

87) There: In the Light and the Darkness of the Self and the Other, by Etel Adnan (1997).

88) Classical Poems by Arab Women: A Bilingual Anthology, ed. Abdullah al-Udhari (2000). This collection has its flaws, but it’s hard to think of any other that attempts a span of 5,000 years, from the pre-Islamic to the Andalusian periods and presents rarely seen work by over fifty women writers. Well-known medieval poets like eulogist Khansa and Wallada bint al-Mustakfi, as well as many more.