When the Adaptation is Better than the Book

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Here at Book Riot, we believe that the book is always better than the movie. It’s even in our mission statement! But what about those times when <whispers> the movie really is better?

Look, this is truly subjective. Some people will always prefer the version in their head, which means book is always best for you. Some people don’t even like movies! That’s cool too. But if you like adaptations of books, hear me out.

I’ve already argued in favor of multiple adaptations of any given work, and I stand by that. Now I am asking you to consider that some stories are best told in certain mediums…and sometimes the best medium isn’t a book. Shocking, I know.

I recently watched Carol, based on Patricia Highsmith’s groundbreaking novel The Price of Salt. I read the novel last year, and it’s very similar stylistically to other mid-century women’s fiction I’ve read (in particular, it reminded me of The Dud Avocado, except that I hated that book and DNF), but it’s about a lesbian relationship. Not only was the subject matter taboo as hell, but Highsmith did the unthinkable and gave the women a happy(ish) ending. (She also published under a pseudonym and denied having written it for nearly 40 years after its publication.) For more on the importance of this story, see Alice’s lovely post, Carol: The Adaptation The Lesbian Community Deserves.

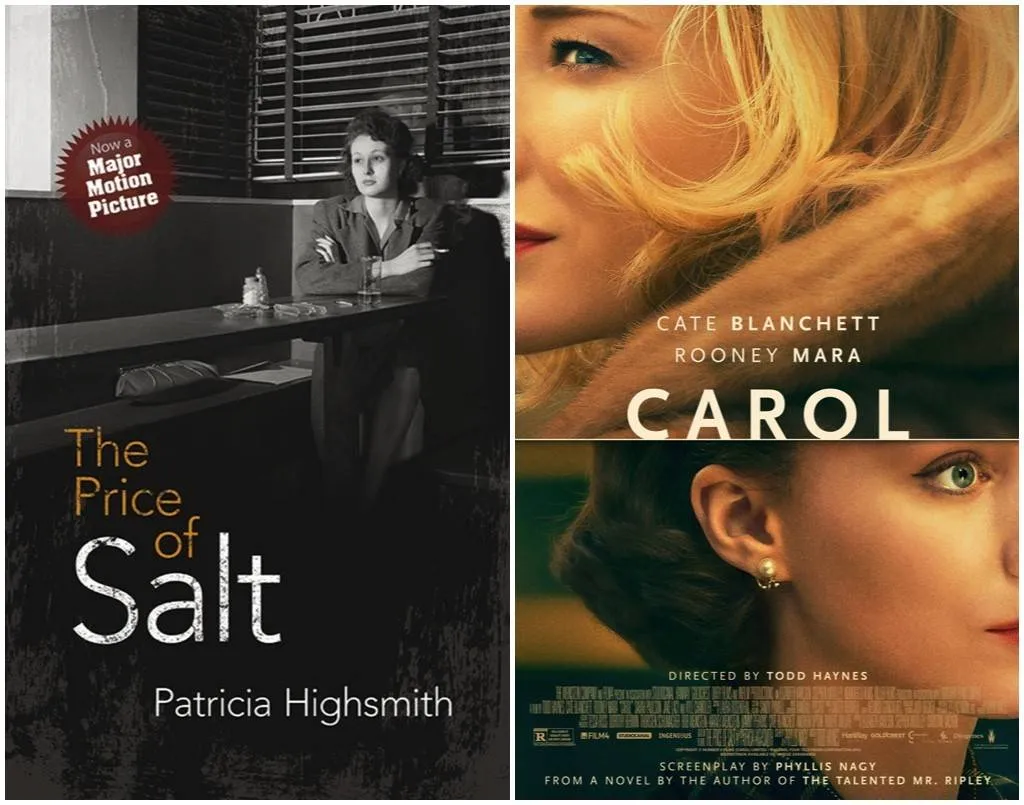

Carol is directed by Todd Haynes, whose 2011 adaptation of Mildred Pierce blew me away. The latter is extremely faithful to the book, nearly to a fault (except that it’s faultless)–but it has the leisure of being faithful, as it’s a miniseries made for HBO. Carol is a feature length film, and as such cannot be as faithful. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing! Haynes and the screenwriter, Phyllis Nagy, who worked on the adaptation for literally decades, made careful changes, small and slightly less small, to perfectly bring the essence of the story to the screen.

Some of the changes are tangible, such as changing Therese’s career aspiration from theater set designer to the presumably more relatable photographer (this change had other advantages, which I discuss below). Others are based on perspective, showing us Carol’s life much in the way that The Hunger Games let us see what was happening in The Capitol while Katniss was in the Arena.

The book is written in third person, and the story told entirely from Therese’s perspective. For the most part, the movie also remains close to Therese’s experience, only occasionally following Carol instead, until the last third or so of the film, when we see first Harge looking for Carol (which is not in the book, though it’s entirely reasonable to assume it happens off the page, as with the scenes in The Hunger Games mentioned above) and later Carol in the custody hearing.

Therese’s photography gives a visual cue to the audience where readers of the book would have more concrete descriptions of what Therese is thinking, and it’s a brilliant choice (made, I believe, by Nagy) that allows the film to still be Therese’s story while no longer being just her story.

Perhaps the biggest change to the story is the near-erasure of Richard, Therese’s boyfriend, who is a dominant character in Therese’s narrative for nearly half of the book, until she leaves him to go away on the road trip with Carol. He (and his friends, who are reimagined for the movie) play a lesser role, but the movie keeps a key moment when Therese, experimenting with the idea that what she is feeling for Carol might be love, asks him if he’s ever been in love with a boy.

In the book, Therese and Carol often say nothing to each other, or don’t say what they mean, and on the page this is infuriating, because the women are hiding their feelings. The movie does not change this, but somehow it becomes enticing and almost suspenseful as the viewer waits for the women to act upon their feelings. A stunning combination of cinematography, performances by the actors, music, and all the trappings of a movie make this possible.

Carol in the book is an object. She is only described as Therese sees her. Carol in the movie must, by necessity, be a full person–indeed, be the main character. Somehow, the movie achieves this while staying true to the book–and the sum of its parts makes it, in my view, superior to the book. You should, of course, read the book, see the movie, and decide for yourself.

I recently watched Carol, based on Patricia Highsmith’s groundbreaking novel The Price of Salt. I read the novel last year, and it’s very similar stylistically to other mid-century women’s fiction I’ve read (in particular, it reminded me of The Dud Avocado, except that I hated that book and DNF), but it’s about a lesbian relationship. Not only was the subject matter taboo as hell, but Highsmith did the unthinkable and gave the women a happy(ish) ending. (She also published under a pseudonym and denied having written it for nearly 40 years after its publication.) For more on the importance of this story, see Alice’s lovely post, Carol: The Adaptation The Lesbian Community Deserves.

Carol is directed by Todd Haynes, whose 2011 adaptation of Mildred Pierce blew me away. The latter is extremely faithful to the book, nearly to a fault (except that it’s faultless)–but it has the leisure of being faithful, as it’s a miniseries made for HBO. Carol is a feature length film, and as such cannot be as faithful. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing! Haynes and the screenwriter, Phyllis Nagy, who worked on the adaptation for literally decades, made careful changes, small and slightly less small, to perfectly bring the essence of the story to the screen.

Some of the changes are tangible, such as changing Therese’s career aspiration from theater set designer to the presumably more relatable photographer (this change had other advantages, which I discuss below). Others are based on perspective, showing us Carol’s life much in the way that The Hunger Games let us see what was happening in The Capitol while Katniss was in the Arena.

The book is written in third person, and the story told entirely from Therese’s perspective. For the most part, the movie also remains close to Therese’s experience, only occasionally following Carol instead, until the last third or so of the film, when we see first Harge looking for Carol (which is not in the book, though it’s entirely reasonable to assume it happens off the page, as with the scenes in The Hunger Games mentioned above) and later Carol in the custody hearing.

Therese’s photography gives a visual cue to the audience where readers of the book would have more concrete descriptions of what Therese is thinking, and it’s a brilliant choice (made, I believe, by Nagy) that allows the film to still be Therese’s story while no longer being just her story.

Perhaps the biggest change to the story is the near-erasure of Richard, Therese’s boyfriend, who is a dominant character in Therese’s narrative for nearly half of the book, until she leaves him to go away on the road trip with Carol. He (and his friends, who are reimagined for the movie) play a lesser role, but the movie keeps a key moment when Therese, experimenting with the idea that what she is feeling for Carol might be love, asks him if he’s ever been in love with a boy.

In the book, Therese and Carol often say nothing to each other, or don’t say what they mean, and on the page this is infuriating, because the women are hiding their feelings. The movie does not change this, but somehow it becomes enticing and almost suspenseful as the viewer waits for the women to act upon their feelings. A stunning combination of cinematography, performances by the actors, music, and all the trappings of a movie make this possible.

Carol in the book is an object. She is only described as Therese sees her. Carol in the movie must, by necessity, be a full person–indeed, be the main character. Somehow, the movie achieves this while staying true to the book–and the sum of its parts makes it, in my view, superior to the book. You should, of course, read the book, see the movie, and decide for yourself.

I recently watched Carol, based on Patricia Highsmith’s groundbreaking novel The Price of Salt. I read the novel last year, and it’s very similar stylistically to other mid-century women’s fiction I’ve read (in particular, it reminded me of The Dud Avocado, except that I hated that book and DNF), but it’s about a lesbian relationship. Not only was the subject matter taboo as hell, but Highsmith did the unthinkable and gave the women a happy(ish) ending. (She also published under a pseudonym and denied having written it for nearly 40 years after its publication.) For more on the importance of this story, see Alice’s lovely post, Carol: The Adaptation The Lesbian Community Deserves.

Carol is directed by Todd Haynes, whose 2011 adaptation of Mildred Pierce blew me away. The latter is extremely faithful to the book, nearly to a fault (except that it’s faultless)–but it has the leisure of being faithful, as it’s a miniseries made for HBO. Carol is a feature length film, and as such cannot be as faithful. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing! Haynes and the screenwriter, Phyllis Nagy, who worked on the adaptation for literally decades, made careful changes, small and slightly less small, to perfectly bring the essence of the story to the screen.

Some of the changes are tangible, such as changing Therese’s career aspiration from theater set designer to the presumably more relatable photographer (this change had other advantages, which I discuss below). Others are based on perspective, showing us Carol’s life much in the way that The Hunger Games let us see what was happening in The Capitol while Katniss was in the Arena.

The book is written in third person, and the story told entirely from Therese’s perspective. For the most part, the movie also remains close to Therese’s experience, only occasionally following Carol instead, until the last third or so of the film, when we see first Harge looking for Carol (which is not in the book, though it’s entirely reasonable to assume it happens off the page, as with the scenes in The Hunger Games mentioned above) and later Carol in the custody hearing.

Therese’s photography gives a visual cue to the audience where readers of the book would have more concrete descriptions of what Therese is thinking, and it’s a brilliant choice (made, I believe, by Nagy) that allows the film to still be Therese’s story while no longer being just her story.

Perhaps the biggest change to the story is the near-erasure of Richard, Therese’s boyfriend, who is a dominant character in Therese’s narrative for nearly half of the book, until she leaves him to go away on the road trip with Carol. He (and his friends, who are reimagined for the movie) play a lesser role, but the movie keeps a key moment when Therese, experimenting with the idea that what she is feeling for Carol might be love, asks him if he’s ever been in love with a boy.

In the book, Therese and Carol often say nothing to each other, or don’t say what they mean, and on the page this is infuriating, because the women are hiding their feelings. The movie does not change this, but somehow it becomes enticing and almost suspenseful as the viewer waits for the women to act upon their feelings. A stunning combination of cinematography, performances by the actors, music, and all the trappings of a movie make this possible.

Carol in the book is an object. She is only described as Therese sees her. Carol in the movie must, by necessity, be a full person–indeed, be the main character. Somehow, the movie achieves this while staying true to the book–and the sum of its parts makes it, in my view, superior to the book. You should, of course, read the book, see the movie, and decide for yourself.

I recently watched Carol, based on Patricia Highsmith’s groundbreaking novel The Price of Salt. I read the novel last year, and it’s very similar stylistically to other mid-century women’s fiction I’ve read (in particular, it reminded me of The Dud Avocado, except that I hated that book and DNF), but it’s about a lesbian relationship. Not only was the subject matter taboo as hell, but Highsmith did the unthinkable and gave the women a happy(ish) ending. (She also published under a pseudonym and denied having written it for nearly 40 years after its publication.) For more on the importance of this story, see Alice’s lovely post, Carol: The Adaptation The Lesbian Community Deserves.

Carol is directed by Todd Haynes, whose 2011 adaptation of Mildred Pierce blew me away. The latter is extremely faithful to the book, nearly to a fault (except that it’s faultless)–but it has the leisure of being faithful, as it’s a miniseries made for HBO. Carol is a feature length film, and as such cannot be as faithful. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing! Haynes and the screenwriter, Phyllis Nagy, who worked on the adaptation for literally decades, made careful changes, small and slightly less small, to perfectly bring the essence of the story to the screen.

Some of the changes are tangible, such as changing Therese’s career aspiration from theater set designer to the presumably more relatable photographer (this change had other advantages, which I discuss below). Others are based on perspective, showing us Carol’s life much in the way that The Hunger Games let us see what was happening in The Capitol while Katniss was in the Arena.

The book is written in third person, and the story told entirely from Therese’s perspective. For the most part, the movie also remains close to Therese’s experience, only occasionally following Carol instead, until the last third or so of the film, when we see first Harge looking for Carol (which is not in the book, though it’s entirely reasonable to assume it happens off the page, as with the scenes in The Hunger Games mentioned above) and later Carol in the custody hearing.

Therese’s photography gives a visual cue to the audience where readers of the book would have more concrete descriptions of what Therese is thinking, and it’s a brilliant choice (made, I believe, by Nagy) that allows the film to still be Therese’s story while no longer being just her story.

Perhaps the biggest change to the story is the near-erasure of Richard, Therese’s boyfriend, who is a dominant character in Therese’s narrative for nearly half of the book, until she leaves him to go away on the road trip with Carol. He (and his friends, who are reimagined for the movie) play a lesser role, but the movie keeps a key moment when Therese, experimenting with the idea that what she is feeling for Carol might be love, asks him if he’s ever been in love with a boy.

In the book, Therese and Carol often say nothing to each other, or don’t say what they mean, and on the page this is infuriating, because the women are hiding their feelings. The movie does not change this, but somehow it becomes enticing and almost suspenseful as the viewer waits for the women to act upon their feelings. A stunning combination of cinematography, performances by the actors, music, and all the trappings of a movie make this possible.

Carol in the book is an object. She is only described as Therese sees her. Carol in the movie must, by necessity, be a full person–indeed, be the main character. Somehow, the movie achieves this while staying true to the book–and the sum of its parts makes it, in my view, superior to the book. You should, of course, read the book, see the movie, and decide for yourself.