Jessica Valenti on Sex Positivity, Ferrante, and SEX OBJECT

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

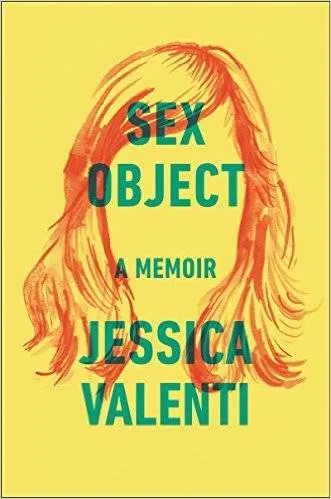

(photo by Leslie Hassler)

SA: Speaking of Roxane Gay… when I read Full Frontal Feminism back in the day, and as I followed the content on Feministing and elsewhere, I couldn’t help feeling: hey, these women are the real deal. I don’t think I’m a good enough feminist. Can I be a feminist and still feel this, or still do that? And then I read Bad Feminist last year and was like hallelujah! In reading Sex Object, I was surprised to see you call out your own impostor syndrome. What are the ways in which you feel you, yourself, are a “bad feminist,” and how do you push past that feeling to continue doing the work you do?

JV: I think for me, it wasn’t necessarily about any one thing. When you do this work online and you have a semi-public face in the movement, you create a narrative for who you are and what you do. But it didn’t necessarily feel as if I was telling the full story. I would start talking to younger women and they would ask me, “How do you handle online harassment so well?” And I would think I’m not handling it at all! I’m such a mess! It made me realize that what I was presenting was not the full story, and that I was doing these women a disservice in some way. It’s part of the reason I wanted to write this book. There’s a sense that if you’re a feminist fighting all of these issues, you’re always sure of yourself and you always know exactly what the answer is. What’s great about Roxane is that she really opened up the conversation so that people could see it was much more complicated than that.

SA: If I could just briefly get book nerdy again, are there any modern literary protagonists that you feel really illustrate that complexity effectively? Do you think there are any novelists portraying this complexity especially well?

JV: The really obvious answer, because everyone’s talking about her, is Elena Ferrante. I don’t have a lot of time to read for fun, but I made time for those and I just ate them up. The complexity of female characters and the complexity of the friendships she portrays are so heartening and, sadly, unusual. But it brought me a lot of joy.

SA: Getting a bit more personal… I find that the things we write about naturally shift as our lives shift. And I can see that arc in your books. How do you feel that the trajectory of your work—and perhaps even your definition of feminism—has shifted along with the trajectory of your life?

JV: I don’t know that my definition of feminism has changed a lot over the years, though my understanding of feminism has shifted and changed as I’ve been exposed to new ideas and new writers. But becoming a mother has definitely made a lot of the issues more urgent for me. The most stark change for me was having my daughter and realizing that she’s going to grow up in this world. It’s made me think about how I want to explain all of this to her.

SA: Absolutely, especially in light of the number of sex-negative experiences you’ve had over the course of your life. And indeed, the title of your book places a spotlight on the ways in which we as women are constantly sexualized. With all that you’ve experienced, what role has sex-positive feminism played in your life?

JV: I think sex-positive feminism is incredibly important, and it’s played a huge part in my life. Honestly, thinking about sexuality through a feminist lens is what has made all of the bad stuff bearable. It is what has made me grow into a better person, I think, and a healthier person.

SA: Going back to the ways in which women are so often sexualized, I was very much struck by several points in your book where you point out how women tend to prioritize men’s comfort over their own. It rang so true for me. Do you think there’s a viable way for women to prioritize their own comfort and self-agency without forfeiting their sense of safety? Do you think it’s something we should be trying to do and, if so, how would you recommend women begin pushing back?

JV: I hope so. I want that, but I think what you just said about safety is such an important piece of it. The safety aspect is so dependent upon the situation. It’s one thing to prioritize comfort if you’re not in jeopardy. It’s more difficult to do it on the street if you don’t have a sense of what your safety level is. And I don’t think it’s something we can demand of women. Every woman has grown up being able to assess a situation, and only in that moment can we make a decision as to what the right move is. It continues to be a problem and it’s one of the reasons I wanted to write about it. I still do that. I still prioritize men’s comfort over my own, and I don’t think that’s an unusual thing.

SA: Shifting gears, Andi Zeisler’s We Were Feminists Once is still on my TBR pile, but I’ve read several interviews with her in which she calls out the commodification of feminism, and the ways in which we tend to call all acts feminist acts, or empowering acts. What are your thoughts on this shift?

JA: I think Andi’s onto something. I think that’s a really smart analysis. So much of our work—and certainly mine 10 years ago—has been in making feminism more accessible and in making people want to call themselves feminist. Now, feminism is this popular thing. It wields so much cultural power. The fact that people want to appropriate it… that’s the good news. The bad news, beyond commercialism, is that the label and the language of feminism are often now used in ways that don’t always line up with what feminism is all about. I’m concerned with how the right is co-opting the word “feminist,” and co-opting feminist rhetoric. As an example, anti-choice advocates have, for years, been calling women who choose to get abortions murderers. Lately, however, they’ve changed their language. They say that they are focused on protecting women’s health. I think that’s the most dangerous piece of this co-opting: that conservative organizations—particularly anti-feminist organizations and legislators—are using feminist language to push an anti-woman agenda.

SA: Before we run out of time, and for those who are still on the fence about picking up your latest book, what lesson do you hope readers take away from Sex Object?

JV: I do hope some of the experiences I’ve had will resonate with a lot of people. As for an overall message, I want readers to know it’s okay to be sort of a mess sometimes. It’s okay to fuck up and not always do the right thing. It’s pretty common and that’s okay. I’m concerned about this mainstream message that women need to project a lot of outer strength. I get why that is, but there is also power in embracing the ways in which we are vulnerable and in talking about that and living in a little bit of discomfort.

SA: Speaking of Roxane Gay… when I read Full Frontal Feminism back in the day, and as I followed the content on Feministing and elsewhere, I couldn’t help feeling: hey, these women are the real deal. I don’t think I’m a good enough feminist. Can I be a feminist and still feel this, or still do that? And then I read Bad Feminist last year and was like hallelujah! In reading Sex Object, I was surprised to see you call out your own impostor syndrome. What are the ways in which you feel you, yourself, are a “bad feminist,” and how do you push past that feeling to continue doing the work you do?

JV: I think for me, it wasn’t necessarily about any one thing. When you do this work online and you have a semi-public face in the movement, you create a narrative for who you are and what you do. But it didn’t necessarily feel as if I was telling the full story. I would start talking to younger women and they would ask me, “How do you handle online harassment so well?” And I would think I’m not handling it at all! I’m such a mess! It made me realize that what I was presenting was not the full story, and that I was doing these women a disservice in some way. It’s part of the reason I wanted to write this book. There’s a sense that if you’re a feminist fighting all of these issues, you’re always sure of yourself and you always know exactly what the answer is. What’s great about Roxane is that she really opened up the conversation so that people could see it was much more complicated than that.

SA: If I could just briefly get book nerdy again, are there any modern literary protagonists that you feel really illustrate that complexity effectively? Do you think there are any novelists portraying this complexity especially well?

JV: The really obvious answer, because everyone’s talking about her, is Elena Ferrante. I don’t have a lot of time to read for fun, but I made time for those and I just ate them up. The complexity of female characters and the complexity of the friendships she portrays are so heartening and, sadly, unusual. But it brought me a lot of joy.

SA: Getting a bit more personal… I find that the things we write about naturally shift as our lives shift. And I can see that arc in your books. How do you feel that the trajectory of your work—and perhaps even your definition of feminism—has shifted along with the trajectory of your life?

JV: I don’t know that my definition of feminism has changed a lot over the years, though my understanding of feminism has shifted and changed as I’ve been exposed to new ideas and new writers. But becoming a mother has definitely made a lot of the issues more urgent for me. The most stark change for me was having my daughter and realizing that she’s going to grow up in this world. It’s made me think about how I want to explain all of this to her.

SA: Absolutely, especially in light of the number of sex-negative experiences you’ve had over the course of your life. And indeed, the title of your book places a spotlight on the ways in which we as women are constantly sexualized. With all that you’ve experienced, what role has sex-positive feminism played in your life?

JV: I think sex-positive feminism is incredibly important, and it’s played a huge part in my life. Honestly, thinking about sexuality through a feminist lens is what has made all of the bad stuff bearable. It is what has made me grow into a better person, I think, and a healthier person.

SA: Going back to the ways in which women are so often sexualized, I was very much struck by several points in your book where you point out how women tend to prioritize men’s comfort over their own. It rang so true for me. Do you think there’s a viable way for women to prioritize their own comfort and self-agency without forfeiting their sense of safety? Do you think it’s something we should be trying to do and, if so, how would you recommend women begin pushing back?

JV: I hope so. I want that, but I think what you just said about safety is such an important piece of it. The safety aspect is so dependent upon the situation. It’s one thing to prioritize comfort if you’re not in jeopardy. It’s more difficult to do it on the street if you don’t have a sense of what your safety level is. And I don’t think it’s something we can demand of women. Every woman has grown up being able to assess a situation, and only in that moment can we make a decision as to what the right move is. It continues to be a problem and it’s one of the reasons I wanted to write about it. I still do that. I still prioritize men’s comfort over my own, and I don’t think that’s an unusual thing.

SA: Shifting gears, Andi Zeisler’s We Were Feminists Once is still on my TBR pile, but I’ve read several interviews with her in which she calls out the commodification of feminism, and the ways in which we tend to call all acts feminist acts, or empowering acts. What are your thoughts on this shift?

JA: I think Andi’s onto something. I think that’s a really smart analysis. So much of our work—and certainly mine 10 years ago—has been in making feminism more accessible and in making people want to call themselves feminist. Now, feminism is this popular thing. It wields so much cultural power. The fact that people want to appropriate it… that’s the good news. The bad news, beyond commercialism, is that the label and the language of feminism are often now used in ways that don’t always line up with what feminism is all about. I’m concerned with how the right is co-opting the word “feminist,” and co-opting feminist rhetoric. As an example, anti-choice advocates have, for years, been calling women who choose to get abortions murderers. Lately, however, they’ve changed their language. They say that they are focused on protecting women’s health. I think that’s the most dangerous piece of this co-opting: that conservative organizations—particularly anti-feminist organizations and legislators—are using feminist language to push an anti-woman agenda.

SA: Before we run out of time, and for those who are still on the fence about picking up your latest book, what lesson do you hope readers take away from Sex Object?

JV: I do hope some of the experiences I’ve had will resonate with a lot of people. As for an overall message, I want readers to know it’s okay to be sort of a mess sometimes. It’s okay to fuck up and not always do the right thing. It’s pretty common and that’s okay. I’m concerned about this mainstream message that women need to project a lot of outer strength. I get why that is, but there is also power in embracing the ways in which we are vulnerable and in talking about that and living in a little bit of discomfort.