Black Speculative Fiction is Protest Work

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

The post you’re reading is part of Book Riot’s observance of #BlackOutDay. We are turning our attention fully to issues facing black authors and readers with help from the folks at #BlackoutDay and #WeNeedDiverseBooks. Book Riot is grateful to have a platform to celebrate diversity and critically examine the book world every day, but today we have turned the reins over to our black contributors and guest contributors all working towards social justice and good books. Enjoy!

____________________

“As long as there are only one, two, or a handful of us, however, I presume in a field such as science fiction, where many of its writers come out of the liberal-Jewish tradition, prejudice will most likely remain a slight force…” –Samuel Delany

Speculative fiction–the catchall term for literature that fits into distinct genres like fantasy, science fiction, and horror–has long been a place of refuge for readers who long to live in far flung futures, or who wish to explore alternate universes. The largest strength of speculative fiction, and its biggest draw, is that it allows readers and fans to become completely lost in its cultures, communities, and creations. The worlds created by speculative fiction authors can be radically different from our own, and are sometimes free of the mundane sociopolitical realism of this Planet Earth.

Despite this, authors, fans, industry employees, and other proponents of the genre cannot completely escape these trappings. The lines between real and fictional worlds are very much influenced by the deep divisions between real world people who interact with the art. Bias and problematic political views slip through (when they weren’t already present to begin with), infecting these real world communities with discrimination and outright hostility to members of certain communities. No recent event illustrates this phenomenon more than the half-dead controversy surrounding the Hugo awards.

Early-to-mid 2015 saw the rise of a group of conservative leaning science fiction authors who believed themselves and their work to be victims of some complex scheme perpetrated by a shadowy legion of queer, non-binary, disabled, and non-white authors working alongside their industry shill allies. This scheme, according to them, tainted the validity and quality of the one of the most important literary prizes in speculative literature by presenting the award to the work of inherently less qualified and less talented marginalized authors over that of themselves and a handpicked group of their approved creators. This group of authors and supporters organized what they considered a populist protest, manipulating the selection process of one of speculative fiction’s highest and most recognizable awards. Their rallying cry? “…they never wanted any of us.”

This is an ironic position given the historically damaging treatment of marginalized people, specifically African American people, by the speculative fiction industry and its attendant fandom. Consider that one of the main participants in this movement referred to a popular African American speculative fiction author as a “half-savage.” Fans of this man claim to be ignorant of the racial undertones of the term, despite blackness’ repeated connection to savagery by heroes of the genre. The community itself, when it gathers, is often hostile to black people and the perceived upheaval of long held norms and traditions that the invasion of their blackness represents. Aggressions large and small are pointed like sharpened stakes at those African Americans who would dare attempt to penetrate this culture with their work, body, or interest. Gatherings and conventions of the larger fandom are often uncomfortable for African American creators and fans, and can be stressful to the point of anxiety. Our work is rarely celebrated, but we produce it despite the larger culture’s resistance to it. We push ourselves against the oppression with our words and effort. Why? Because we have always done so.

“There is nothing new under the sun. But there are new suns.” – Octavia Butler

African American literature has long contained a deep thread of dissent. In a way, African American literature itself is protest, as slaves and the descendants of slaves were often forbidden from attempting to master the language of their oppressors. Historically, literature produced by African Americans served as a way of reckoning with their unique social situation, either through philosophical rumination, haunting memoir, lyrical prose and poetry or a purposeful, shocking address of the conditions that surrounded them. Consider the narratives of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs, who painted a vivid portrait of United States system of violence and psychological terrorism on the African American populace. Or, perhaps, Victor Séjour’s Le Mulâtre, or Martin Delany’s Blake or The Huts of America, both brooding fictional works of slave revolution.

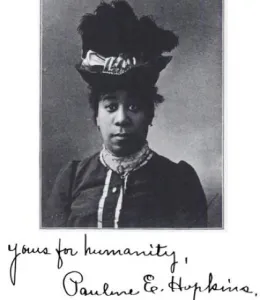

Faced with seemingly unending oppression and the constant threat of violence and death, is it any wonder that African American authors turned to the fantastic to assuage their weary souls? Like Séjour, Delany, and countless others, African American authors of proto speculative fiction heavily considered the future, the fantastic, and the scientific in their attempt to reckon with their present. Pauline Hopkins’ Of One Blood imagines a technologically advanced Ethiopia. Scholar W.E.B. DuBois’ The Comet imagines a post-apocalyptic future world populated by two people: an African American man and a white woman. Frances E.W. Harper’s Iola Leroy is a work of fiction that imagines an African American feminist utopia.

Decades after these works, literary scholars spurred by “an interest in speculative fiction from the African Diaspora” turned to a new and different mode of expression, some of which was championed by existing African American authors of speculative fiction. The work of those authors dealt explicitly with the concerns of members of the African Diaspora contextualized within the idea of a rapidly approaching technofuture. The authors are recognizable: Samuel Delany. Nalo Hopkinson. Sheree Renée Thomas. Octavia Butler. The expression was called “Afrofuturism” and it intersected primarily with speculative fiction, often serving as a means of social and political protest of issues salient to members of the African Diaspora. Black speculative fiction authors who identified as Afrofuturists synthesized the early themes of futurism and necessary upheaval in the form of protest with the idea of a “future history” and deep appreciation of our unique cultures to create a revolutionary genre of literature, a genre that worked closely with and alongside other forms of black speculative fiction to remove the idea of black savagery and black catastrophe from our history, mythology, spacetime, and futurescape.

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” – Audre Lorde

Speculative fiction, or “visionary fiction,” as it is termed by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, is all about alternatives. There is a familiar, tragic thread winding through the year of 2015. Physical and emotional violence against African American people is at an all time high. African American women, children, and men are being killed by police in the streets or in their custody. African American parishioners, in a strange twist on a deeply wounding act of racial violence, have been killed in their places of worship. This is a stark, dreadful reality that demands alternative visions, alternative universes, and radical imaginations. It demands that we work we create, if we wish it to have any lasting heft as tools of social justice, aggressively and holistically address the social ills that plague African Americans.

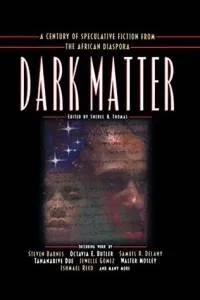

With the specters of death, poverty, and inequality still surrounding African American communities, many African American creators of speculative fiction are illuminating their desire for change in the pages of their literature. The fiction in Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements dares to imagine a world that is fair and equal to one of its most maligned communities. The stories in Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction From the African Diaspora , demand a reckoning. Fiction like Elysium, Who Fears Death, and The Liminal People show us that a new type of mythology is required for these alternate universes and futures and that #BlackLivesMatter in the midst of them.

Most recently, a group of authors and artists including Tananarive Due, Sofia Samatar, Nalo Hopkinson, John Jennings, Andrea Hairston, Nisi Shawl, Daniel José Older, and Steven Barnes came together in a collaboration to discuss the plotting of a “different course forward”, where those who enjoy speculative fiction of all kinds can work to create and engage in new, revolutionary futures. The title of the symposium? “Black to the Future.” This is a play on the title of a popular, future-gazing science fiction film, while simultaneously being a promise. Black people are here in the speculative fiction industry and in its fandom spaces. We will be in the alternate universes, in the re-imagined histories, and in the brightest futures. This new paradigm will be difficult to accept for people like those I mentioned earlier, those who traffic in intolerance, backward views, and discrimination. For them, I will quote a statement that is often heard in African American communities, as a symbol of resistance and protest against those who would seek to oppress. For those who wish to stand in the way of progress and black presence in speculative fiction industries and futures, “You may collectively kiss my black ass.”

With the specters of death, poverty, and inequality still surrounding African American communities, many African American creators of speculative fiction are illuminating their desire for change in the pages of their literature. The fiction in Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements dares to imagine a world that is fair and equal to one of its most maligned communities. The stories in Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction From the African Diaspora , demand a reckoning. Fiction like Elysium, Who Fears Death, and The Liminal People show us that a new type of mythology is required for these alternate universes and futures and that #BlackLivesMatter in the midst of them.

Most recently, a group of authors and artists including Tananarive Due, Sofia Samatar, Nalo Hopkinson, John Jennings, Andrea Hairston, Nisi Shawl, Daniel José Older, and Steven Barnes came together in a collaboration to discuss the plotting of a “different course forward”, where those who enjoy speculative fiction of all kinds can work to create and engage in new, revolutionary futures. The title of the symposium? “Black to the Future.” This is a play on the title of a popular, future-gazing science fiction film, while simultaneously being a promise. Black people are here in the speculative fiction industry and in its fandom spaces. We will be in the alternate universes, in the re-imagined histories, and in the brightest futures. This new paradigm will be difficult to accept for people like those I mentioned earlier, those who traffic in intolerance, backward views, and discrimination. For them, I will quote a statement that is often heard in African American communities, as a symbol of resistance and protest against those who would seek to oppress. For those who wish to stand in the way of progress and black presence in speculative fiction industries and futures, “You may collectively kiss my black ass.”

With the specters of death, poverty, and inequality still surrounding African American communities, many African American creators of speculative fiction are illuminating their desire for change in the pages of their literature. The fiction in Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements dares to imagine a world that is fair and equal to one of its most maligned communities. The stories in Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction From the African Diaspora , demand a reckoning. Fiction like Elysium, Who Fears Death, and The Liminal People show us that a new type of mythology is required for these alternate universes and futures and that #BlackLivesMatter in the midst of them.

Most recently, a group of authors and artists including Tananarive Due, Sofia Samatar, Nalo Hopkinson, John Jennings, Andrea Hairston, Nisi Shawl, Daniel José Older, and Steven Barnes came together in a collaboration to discuss the plotting of a “different course forward”, where those who enjoy speculative fiction of all kinds can work to create and engage in new, revolutionary futures. The title of the symposium? “Black to the Future.” This is a play on the title of a popular, future-gazing science fiction film, while simultaneously being a promise. Black people are here in the speculative fiction industry and in its fandom spaces. We will be in the alternate universes, in the re-imagined histories, and in the brightest futures. This new paradigm will be difficult to accept for people like those I mentioned earlier, those who traffic in intolerance, backward views, and discrimination. For them, I will quote a statement that is often heard in African American communities, as a symbol of resistance and protest against those who would seek to oppress. For those who wish to stand in the way of progress and black presence in speculative fiction industries and futures, “You may collectively kiss my black ass.”

With the specters of death, poverty, and inequality still surrounding African American communities, many African American creators of speculative fiction are illuminating their desire for change in the pages of their literature. The fiction in Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements dares to imagine a world that is fair and equal to one of its most maligned communities. The stories in Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction From the African Diaspora , demand a reckoning. Fiction like Elysium, Who Fears Death, and The Liminal People show us that a new type of mythology is required for these alternate universes and futures and that #BlackLivesMatter in the midst of them.

Most recently, a group of authors and artists including Tananarive Due, Sofia Samatar, Nalo Hopkinson, John Jennings, Andrea Hairston, Nisi Shawl, Daniel José Older, and Steven Barnes came together in a collaboration to discuss the plotting of a “different course forward”, where those who enjoy speculative fiction of all kinds can work to create and engage in new, revolutionary futures. The title of the symposium? “Black to the Future.” This is a play on the title of a popular, future-gazing science fiction film, while simultaneously being a promise. Black people are here in the speculative fiction industry and in its fandom spaces. We will be in the alternate universes, in the re-imagined histories, and in the brightest futures. This new paradigm will be difficult to accept for people like those I mentioned earlier, those who traffic in intolerance, backward views, and discrimination. For them, I will quote a statement that is often heard in African American communities, as a symbol of resistance and protest against those who would seek to oppress. For those who wish to stand in the way of progress and black presence in speculative fiction industries and futures, “You may collectively kiss my black ass.”