Nurdfighters for Paul Zindel: A.S. King Talks Adult Characters, Darkness, and the Ahistoricity of YA

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

At Book Expo America this year, I had the pleasure of sitting down with the inimitable A.S. King to talk, not so much about her work, but the work of Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Zindel. Paul Zindel was a writer you might have encountered in school; his 1968 novel The Pigman was a huge seller and a major pioneer in the genre of YA literature. And yet in spite of the ubiquity of that title, you’d be forgiven in you haven’t thought about Paul Zindel since school — his name seems to be missing from much of the contemporary discussion of YA literature. A.S. King and I sat down to discuss why that is.

Brenna: Ok, I’m going to just frame this up. You and I were talking on Twitter one day about Paul Zindel and his influence on YA and how he seems to be lost in the conversation about young adult literature.

A.S. King: At the moment, yeah. I mean, we have a lot of people like that, and there were people before that. Judy Blume, of course, and so many people even before that who I can’t name right now because it’s a little early in the morning! But Paul Zindel, for me, was my biggest influence. I was sort of a lost kid when I hit junior high school. I’d been this gifted kid who was doing advanced algebra and everything when I was in elementary school, and then when I got to junior high school I was bullied and it was all kinds of messed up. And then my education just fell. I went into basic math courses and they bored me.

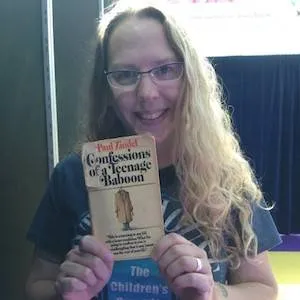

So I found Paul Zindel thanks to my seventh grade teacher who assigned The Pigman, and I loved it. So I went to the library, and they had everything and I took it all. They no longer have everything because I stole it. And I’ve admitted this, and I’ve admitted it all over the country, and I know it’s a horrible thing, and I love librarians and work in my library. I feel horrible having done this and I will eventually pay back the Exeter Junior High School library. But I stole and continued to reread Paul Zindel, and Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, which is what I want to talk a little bit about today, is the one that really got me.

People ask how I get emotional detail into my books, and there’s this one scene I remembered vividly, even before I reread the book. This kid has to pee into a milk bottle. Because his mother is a travelling nurse, an in-home nurse, so they live in other people’s homes. And when the boy is in a room farther from the bathroom, she gives him a milk bottle to pee in. And I found this to be such a detail: the depth of what it must be, the humiliation that must come along with peeing in a milk bottle because your mom tells you you have to. And at his age, I think he’s about sixteen in the book. I’ve been talking about this for years, and that’s how I decided it was about time to pick up the book again.

I teach up at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and for my students’ bibliographies I always tell them, “You have to read a book written for young people before the date of your birth.” Now, obviously I was born before 1977 when Confessions of a Teenage Baboon was published, but what I found in this and in all of Zindel’s work is that adult characters reign. They reign in his books! In Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, even though Christopher Boyd is the narrator, the main characters are Lloyd Dipardi, an alcoholic depressive in his thirties; his mother, who’s dying; Christopher’s mother, who’s the nurse. And then there’s one other teen character and a few who come in and out. But the main characters are all adults. And the plot, especially towards the end (no spoilers!) is definitely about the adults, all seen through this kid’s eyes. Which is realistic!

Brenna: It is realistic, and it’s interesting, because one of the things that I like about your work is that the adult characters are these complex people who mess up, and their mess ups impact their kids. And that’s life, right? It’s really interesting to me how recent YA seems to often excise the parents, especially a lot of the really popular titles. Let’s have a convenient excuse to get the parents out of the picture. Boarding school is always really useful for that.

A.S. King: Exactly. And there’s certain things, like dystopia for example, where there’s a reason to get rid of all the parents. And I read pretty widely, so for the last few years as I’ve been stuck in my own book I’ve been reading a lot of surrealism, so I haven’t had my head in YA. But yes. What happened to me was that when I tried to sell Please Ignore Vera Dietz, I had editors who wanted to cut out the father’s voice and the flow charts. The idea was that teens only want to read about teens, and I can’t understand why anybody would box a group in like that. I know publishing is aiming towards a box and I understand that they’re trying to sell a product. But teenagers don’t fit into a box. Same as women don’t. Same as — none of us. We don’t.

So when I reread Paul Zindel’s work: wow. People always say to me, “Oh, you have all these adult characters and they’re really well-formed.” Well, yeah. Because my whole life was run by adults. I was the youngest in my family, so my sisters were even adults by the time I was a teenager. And then the coaches and the teachers — all these people were adults! So I couldn’t understand why there weren’t more books for teens that had adult characters. So it was great to go back to Zindel. Because he never flinched when it came to it. And I’ve always had adult characters in my books, even the unpublished ones, they’ve always been there. And I didn’t remember that in Zindel, but as I’m reading these books now I’m seeing just how much of his work influenced me long long long ago.

There was an article recently in the Boston Globe, if I’m correct — and I spoke to the author, who was lovely, and she recounted my experiences with the sale of Vera Dietz — but when she wrote the article she framed it as though adult characters are coming back in teen fiction. Which is probably true, based on what you said, a lot of recent work hasn’t had adults in it though mine always has. But I was writing adults in young adult fiction before I was a parent. None of that mattered. It mattered that my teen experience was run by adults. And I think every teen experience is.

Brenna: I think of it in terms of a trope that gets carried over from children’s literature. Because in children’s literature for middle grade and younger, you have to get rid of the parents so the characters can have that experience that takes them into experience. But I think fully formed adult characters are essential to young adult literature because those are the relationships that teenagers are trying to learn to negotiate. Most of them know how to talk to other teenagers. It’s adults who are frightening.

A.S. King: Absolutely. Because, I mean, when you look at the Hero’s Journey or any of these common ways of telling stories, you do have to get rid of the parents for younger readers. But even in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, Chris is truly changed by Lloyd. This is a heavy book. It isn’t a light book.

Brenna: And that’s something I want to come back to. When I was rereading Pigman on the plane on the way east I was thinking, wow, this whole notion that YA suddenly got dark in 2004 —

A.S. King: Yes! That’s what happened to me when I finished this book! I’m like, ok. First of all, Lloyd Disparti has a bottle of Wild Turkey in his hand from scene one.

Brenna: They’re all drunk! John is drunk all the time in The Pigman. That’s his character’s thing.

A.S. King: And in Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Edna talks about her mother being drunk all the time. These are drunk characters. And these are normal adults, let’s be fair. I look at the cross-section of adults I know, and, well.

But the darkness in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon: look, the mother is a hospice nurse, so we know there’s going to be an elderly person dying. But beyond that things get completely dark at the end of this book. That was the one surprise for me. I thought yeah, ok, adult characters, but I already knew adult characters had always existed. But the darkness was something I almost didn’t expect. Now I remembered the part scene at the end of The Pigman, and because my daughter took it from me and I couldn’t finish it, I haven’t revisited it. But I remember how it made me feel. And also the party scene at the end of Eyeball. So I know there’s a lot of confusion, darkness, all of that. And you’re absolutely right: it’s always been there.

Brenna: People are pretty good now about remembering to bring Judy Blume back into the conversation, but these other figures like Zindel have disappeared. We write about young adult fiction with this really ahistorical eye. Like, whatever’s happening right now is just what is.

A.S. King: But isn’t that what media is doing? When I left America, there was still news. I came back and now there isn’t news. It has turned into newsertainment. So it’s just such a different conversation. Everything has to be new and exciting so that people will watch and not turn the channel. And it’s the same with articles so that people won’t click out. But it is funny how we have reinvented what it means to be YA so that we can be aghast at what has always been.

I mean: Roald Dahl? Aren’t those two words that say dark right there? There’s a giant peach who runs over people and we loved it. We all cheered.

Brenna: I remember my cousin wasn’t allowed to read James and the Giant Peach because her mother thought it was way too violent and she was horrified that I was reading it. And now the idea of that just seems bizarre.

A.S. King: It is bizarre. But we do forget the history. Here’s one for you: when I was rereading Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, and I haven’t had time to research this so I’m just going to throw that out there, when Lloyd wants to insult Christopher, he calls him a nurd. Spelled with a U. So nerd, in 1977, in Paul Zindel’s head, was spelled N-U-R-D. For me, I felt that I could then identify. Paul Zindel saved my life. He really did. He made me feel normal when I was definitely having a hard time in junior high. So I’m a nUrdfighter with a U. And that’s no offence to the nerdfighters with an E. I think both would get along very very well. But it’s the idea that, you know, back then we didn’t have fandoms. I’m not hip on them now but we definitely didn’t have them then.

Brenna: Well you couldn’t connect with people outside of your world. If your friends weren’t reading the same books as you, your fandom was just you and the characters.

A.S. King: This was it. It was just me and Zindel’s characters. Which is part of the reason I took the books — I figured I might as well take them, since I was the only one reading them! (That’s a lie.) So there was no way to have that fandom. If I could create a fandom now for Paul Zindel books, I guess I really can’t steal nUrdfighter with the U, but that would be what I am. Because I realized that in 1982 and 1983, this was what I had. And the darkness didn’t even freak me out. I didn’t blink.

Brenna: I think I was much more disturbed by these books this time than when I read them when I was 13.

A.S. King: My heart is already breaking for Mr. Pignati and I’m not even half-way through rereading The Pigman yet. Because I remember and I know.

Rereading Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Marsh gives us his Hate List and Love List. And I kept a journal from the age of 15, and I did that in my journal. Every day I would have a list of things I loved and a list of things I hated. And that came from Paul Zindel. And in those, Marsh is hysterical about some of the adults in the book — he’s really open about them. But the first four chapters are dedicated to describing the adult characters, Marsh and Edna’s parents. There’s one scene with Edna’s parents in the psychologist’s office and they’re saying to the counsellor that they’ve done everything they can to make Edna acceptable: they’ve pinned her ears, bought these clothes, done this to her hair and nothing has worked because Edna doesn’t have any friends. And they want to know what they can do to get Edna a friend. Of course, Edna doesn’t really want any friends. But it’s the amazing scene that is there to colour Edna’s parents; it’s not really about Edna at all. And the same thing happens with Marsh’s parents right there in the beginning, and I think it’s wonderful.

One thing I find, and I think I have the best editor in the whole business, Andrea Spooner who is a genius, but I’ve worked with other editors as well — when you’re reading a book, or reviewing a book perhaps and that’s why editors have this idea — but people think you need to explain everything in the first fifty pages and it has to be centred toward the main character. And I don’t agree

Brenna: And Zindel definitely resists that.

A.S. King: This is it. For me, I’ve had editors who understand I might introduce a character on page 160. Because why not? That’s how life works. We’re sitting here right now, are we not? You were not introduced in the first fifty pages of my book but you are here. Right? It’s interesting.

When it comes to Zindel, I was really blown away by Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. I guess I really didn’t expect it to be that dark. And the end. This was a reminder that what I’m doing and what other people are doing isn’t new. This isn’t new. We have a history.

Brenna: I would love to see part of the YA powerhouse go back and republish some of these, because they’re hard to find. You can get Pigman on ebook anywhere, but the rest of the novels — if you don’t have an aging village library, you won’t find them. I don’t think you can find them new. If I’m wrong, someone on BookRiot will correct me on that, but Paul Zindel wrote like forty novels and they are not easy to find. The plays are easier, but the novels? No way.

A.S. King: The only thing I’ve found that would be frowned upon now, and rightly should be, is that in Confessions the character takes notice of one other character who is overweight. He takes notice, calling her Susan the Hippo, and he isn’t kind about her weight. Outside of that, though, there’s nothing here that wouldn’t fit into our contemporary culture. Plus, let’s face it, people do still think like that. I’m a big believer that until people stop thinking like that, we have to keep it in books. Plus it was written in 1977 and things were different then. The world wasn’t laced in high fructose corn syrup.

You know, it’s tough to constantly read that this person is the King of YA or the Queen of YA or Inventor of YA.

People might read my books and Paul Zindel’s books and say they’re not the same, because I have a character going through shock who experiences magical realism. But for me, having experienced shock a few times in my life, I don’t find that panicked daydream to be so unrealistic. How do you get through it otherwise? Rereading Zindel re-energized me, because it reminded me that there’s a huge history behind Young Adult. It’s not new. Because we now have it on a shelf we think it’s new. When I left America in the 1990s we didn’t have a shelf, and when I returned it was flying. But I didn’t know what it was.

I’ve always listed Paul Zindel as one of my influences. I just always have.

Brenna: I try to resist worrying about the future because I think the future usually takes care of itself, but I do wonder about the generation of writers who are going to come next. People will find books, because people who love books find books, but my concern is for the literary tradition that is lost. If you grow up thinking that John Green started YA, what parts of the conversation do you miss out on because of that? Book people find books, but there’s a whole hidden tradition there. I’ve been in the YA world for five years and it hadn’t occurred to me to revisit Paul Zindel until you messaged me.

A.S. King: I watched John’s most recent video this morning, and what I love about John is that he recommends books. He always recommends books, and I think it’s wonderful. I think he realizes that there is this huge responsibility on him because the media has said these things and he’s a huge influence on readers. And he’s very conscious of that. So I’m glad he recommends books. But when I read my students’ bibliographies, some of the books they come up with — a YA book from before the year of their birth, even if they’re fifty. And they always do. They never have a problem. So if I vlogged, which I don’t, but if I did, I would recommend Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. But then how would people find it?

Brenna: I would love to see him reissued.

A.S. King: They’re just fantastic books. All of them. And real.

When I was reading Zindel the first time, I remember writing down that when I grew up, I wanted to write books that would help adults understand teens better and help teens understand adults better. And I went home and I told my folks, and they suggested I could be a newspaper writer. As much as I respect newspaper writers, that wasn’t really what I had in mind. But then, only a few years ago, and it took me a few books to realize it: because I include adult characters, I’m doing that. And it’s wonderful. It’s kind of cool.

If I can cut down on the eye rolling when it comes to adults and teenagers, I’ve succeeded.

Here’s what I want to find out: how was Paul Zindel received? What were his reviews like? And who was he writing alongside? I would love to reconstruct YA from the early 1960s to the mid 1980s. But I’d need a clone. Or I need you to do it. One or the other.

But this stuff always existed. The darkness, or as I call it, life, has always existed. I just don’t think it’s changed that much.

But these are my thoughts: I’m a nUrdfighter. My daughter is a nerdfighter. And I love Paul Zindel.

Brenna: Ok, I’m going to just frame this up. You and I were talking on Twitter one day about Paul Zindel and his influence on YA and how he seems to be lost in the conversation about young adult literature.

A.S. King: At the moment, yeah. I mean, we have a lot of people like that, and there were people before that. Judy Blume, of course, and so many people even before that who I can’t name right now because it’s a little early in the morning! But Paul Zindel, for me, was my biggest influence. I was sort of a lost kid when I hit junior high school. I’d been this gifted kid who was doing advanced algebra and everything when I was in elementary school, and then when I got to junior high school I was bullied and it was all kinds of messed up. And then my education just fell. I went into basic math courses and they bored me.

So I found Paul Zindel thanks to my seventh grade teacher who assigned The Pigman, and I loved it. So I went to the library, and they had everything and I took it all. They no longer have everything because I stole it. And I’ve admitted this, and I’ve admitted it all over the country, and I know it’s a horrible thing, and I love librarians and work in my library. I feel horrible having done this and I will eventually pay back the Exeter Junior High School library. But I stole and continued to reread Paul Zindel, and Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, which is what I want to talk a little bit about today, is the one that really got me.

People ask how I get emotional detail into my books, and there’s this one scene I remembered vividly, even before I reread the book. This kid has to pee into a milk bottle. Because his mother is a travelling nurse, an in-home nurse, so they live in other people’s homes. And when the boy is in a room farther from the bathroom, she gives him a milk bottle to pee in. And I found this to be such a detail: the depth of what it must be, the humiliation that must come along with peeing in a milk bottle because your mom tells you you have to. And at his age, I think he’s about sixteen in the book. I’ve been talking about this for years, and that’s how I decided it was about time to pick up the book again.

I teach up at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and for my students’ bibliographies I always tell them, “You have to read a book written for young people before the date of your birth.” Now, obviously I was born before 1977 when Confessions of a Teenage Baboon was published, but what I found in this and in all of Zindel’s work is that adult characters reign. They reign in his books! In Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, even though Christopher Boyd is the narrator, the main characters are Lloyd Dipardi, an alcoholic depressive in his thirties; his mother, who’s dying; Christopher’s mother, who’s the nurse. And then there’s one other teen character and a few who come in and out. But the main characters are all adults. And the plot, especially towards the end (no spoilers!) is definitely about the adults, all seen through this kid’s eyes. Which is realistic!

Brenna: It is realistic, and it’s interesting, because one of the things that I like about your work is that the adult characters are these complex people who mess up, and their mess ups impact their kids. And that’s life, right? It’s really interesting to me how recent YA seems to often excise the parents, especially a lot of the really popular titles. Let’s have a convenient excuse to get the parents out of the picture. Boarding school is always really useful for that.

A.S. King: Exactly. And there’s certain things, like dystopia for example, where there’s a reason to get rid of all the parents. And I read pretty widely, so for the last few years as I’ve been stuck in my own book I’ve been reading a lot of surrealism, so I haven’t had my head in YA. But yes. What happened to me was that when I tried to sell Please Ignore Vera Dietz, I had editors who wanted to cut out the father’s voice and the flow charts. The idea was that teens only want to read about teens, and I can’t understand why anybody would box a group in like that. I know publishing is aiming towards a box and I understand that they’re trying to sell a product. But teenagers don’t fit into a box. Same as women don’t. Same as — none of us. We don’t.

So when I reread Paul Zindel’s work: wow. People always say to me, “Oh, you have all these adult characters and they’re really well-formed.” Well, yeah. Because my whole life was run by adults. I was the youngest in my family, so my sisters were even adults by the time I was a teenager. And then the coaches and the teachers — all these people were adults! So I couldn’t understand why there weren’t more books for teens that had adult characters. So it was great to go back to Zindel. Because he never flinched when it came to it. And I’ve always had adult characters in my books, even the unpublished ones, they’ve always been there. And I didn’t remember that in Zindel, but as I’m reading these books now I’m seeing just how much of his work influenced me long long long ago.

There was an article recently in the Boston Globe, if I’m correct — and I spoke to the author, who was lovely, and she recounted my experiences with the sale of Vera Dietz — but when she wrote the article she framed it as though adult characters are coming back in teen fiction. Which is probably true, based on what you said, a lot of recent work hasn’t had adults in it though mine always has. But I was writing adults in young adult fiction before I was a parent. None of that mattered. It mattered that my teen experience was run by adults. And I think every teen experience is.

Brenna: I think of it in terms of a trope that gets carried over from children’s literature. Because in children’s literature for middle grade and younger, you have to get rid of the parents so the characters can have that experience that takes them into experience. But I think fully formed adult characters are essential to young adult literature because those are the relationships that teenagers are trying to learn to negotiate. Most of them know how to talk to other teenagers. It’s adults who are frightening.

A.S. King: Absolutely. Because, I mean, when you look at the Hero’s Journey or any of these common ways of telling stories, you do have to get rid of the parents for younger readers. But even in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, Chris is truly changed by Lloyd. This is a heavy book. It isn’t a light book.

Brenna: And that’s something I want to come back to. When I was rereading Pigman on the plane on the way east I was thinking, wow, this whole notion that YA suddenly got dark in 2004 —

A.S. King: Yes! That’s what happened to me when I finished this book! I’m like, ok. First of all, Lloyd Disparti has a bottle of Wild Turkey in his hand from scene one.

Brenna: They’re all drunk! John is drunk all the time in The Pigman. That’s his character’s thing.

A.S. King: And in Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Edna talks about her mother being drunk all the time. These are drunk characters. And these are normal adults, let’s be fair. I look at the cross-section of adults I know, and, well.

But the darkness in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon: look, the mother is a hospice nurse, so we know there’s going to be an elderly person dying. But beyond that things get completely dark at the end of this book. That was the one surprise for me. I thought yeah, ok, adult characters, but I already knew adult characters had always existed. But the darkness was something I almost didn’t expect. Now I remembered the part scene at the end of The Pigman, and because my daughter took it from me and I couldn’t finish it, I haven’t revisited it. But I remember how it made me feel. And also the party scene at the end of Eyeball. So I know there’s a lot of confusion, darkness, all of that. And you’re absolutely right: it’s always been there.

Brenna: People are pretty good now about remembering to bring Judy Blume back into the conversation, but these other figures like Zindel have disappeared. We write about young adult fiction with this really ahistorical eye. Like, whatever’s happening right now is just what is.

A.S. King: But isn’t that what media is doing? When I left America, there was still news. I came back and now there isn’t news. It has turned into newsertainment. So it’s just such a different conversation. Everything has to be new and exciting so that people will watch and not turn the channel. And it’s the same with articles so that people won’t click out. But it is funny how we have reinvented what it means to be YA so that we can be aghast at what has always been.

I mean: Roald Dahl? Aren’t those two words that say dark right there? There’s a giant peach who runs over people and we loved it. We all cheered.

Brenna: I remember my cousin wasn’t allowed to read James and the Giant Peach because her mother thought it was way too violent and she was horrified that I was reading it. And now the idea of that just seems bizarre.

A.S. King: It is bizarre. But we do forget the history. Here’s one for you: when I was rereading Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, and I haven’t had time to research this so I’m just going to throw that out there, when Lloyd wants to insult Christopher, he calls him a nurd. Spelled with a U. So nerd, in 1977, in Paul Zindel’s head, was spelled N-U-R-D. For me, I felt that I could then identify. Paul Zindel saved my life. He really did. He made me feel normal when I was definitely having a hard time in junior high. So I’m a nUrdfighter with a U. And that’s no offence to the nerdfighters with an E. I think both would get along very very well. But it’s the idea that, you know, back then we didn’t have fandoms. I’m not hip on them now but we definitely didn’t have them then.

Brenna: Well you couldn’t connect with people outside of your world. If your friends weren’t reading the same books as you, your fandom was just you and the characters.

A.S. King: This was it. It was just me and Zindel’s characters. Which is part of the reason I took the books — I figured I might as well take them, since I was the only one reading them! (That’s a lie.) So there was no way to have that fandom. If I could create a fandom now for Paul Zindel books, I guess I really can’t steal nUrdfighter with the U, but that would be what I am. Because I realized that in 1982 and 1983, this was what I had. And the darkness didn’t even freak me out. I didn’t blink.

Brenna: I think I was much more disturbed by these books this time than when I read them when I was 13.

A.S. King: My heart is already breaking for Mr. Pignati and I’m not even half-way through rereading The Pigman yet. Because I remember and I know.

Rereading Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Marsh gives us his Hate List and Love List. And I kept a journal from the age of 15, and I did that in my journal. Every day I would have a list of things I loved and a list of things I hated. And that came from Paul Zindel. And in those, Marsh is hysterical about some of the adults in the book — he’s really open about them. But the first four chapters are dedicated to describing the adult characters, Marsh and Edna’s parents. There’s one scene with Edna’s parents in the psychologist’s office and they’re saying to the counsellor that they’ve done everything they can to make Edna acceptable: they’ve pinned her ears, bought these clothes, done this to her hair and nothing has worked because Edna doesn’t have any friends. And they want to know what they can do to get Edna a friend. Of course, Edna doesn’t really want any friends. But it’s the amazing scene that is there to colour Edna’s parents; it’s not really about Edna at all. And the same thing happens with Marsh’s parents right there in the beginning, and I think it’s wonderful.

One thing I find, and I think I have the best editor in the whole business, Andrea Spooner who is a genius, but I’ve worked with other editors as well — when you’re reading a book, or reviewing a book perhaps and that’s why editors have this idea — but people think you need to explain everything in the first fifty pages and it has to be centred toward the main character. And I don’t agree

Brenna: And Zindel definitely resists that.

A.S. King: This is it. For me, I’ve had editors who understand I might introduce a character on page 160. Because why not? That’s how life works. We’re sitting here right now, are we not? You were not introduced in the first fifty pages of my book but you are here. Right? It’s interesting.

When it comes to Zindel, I was really blown away by Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. I guess I really didn’t expect it to be that dark. And the end. This was a reminder that what I’m doing and what other people are doing isn’t new. This isn’t new. We have a history.

Brenna: I would love to see part of the YA powerhouse go back and republish some of these, because they’re hard to find. You can get Pigman on ebook anywhere, but the rest of the novels — if you don’t have an aging village library, you won’t find them. I don’t think you can find them new. If I’m wrong, someone on BookRiot will correct me on that, but Paul Zindel wrote like forty novels and they are not easy to find. The plays are easier, but the novels? No way.

A.S. King: The only thing I’ve found that would be frowned upon now, and rightly should be, is that in Confessions the character takes notice of one other character who is overweight. He takes notice, calling her Susan the Hippo, and he isn’t kind about her weight. Outside of that, though, there’s nothing here that wouldn’t fit into our contemporary culture. Plus, let’s face it, people do still think like that. I’m a big believer that until people stop thinking like that, we have to keep it in books. Plus it was written in 1977 and things were different then. The world wasn’t laced in high fructose corn syrup.

You know, it’s tough to constantly read that this person is the King of YA or the Queen of YA or Inventor of YA.

People might read my books and Paul Zindel’s books and say they’re not the same, because I have a character going through shock who experiences magical realism. But for me, having experienced shock a few times in my life, I don’t find that panicked daydream to be so unrealistic. How do you get through it otherwise? Rereading Zindel re-energized me, because it reminded me that there’s a huge history behind Young Adult. It’s not new. Because we now have it on a shelf we think it’s new. When I left America in the 1990s we didn’t have a shelf, and when I returned it was flying. But I didn’t know what it was.

I’ve always listed Paul Zindel as one of my influences. I just always have.

Brenna: I try to resist worrying about the future because I think the future usually takes care of itself, but I do wonder about the generation of writers who are going to come next. People will find books, because people who love books find books, but my concern is for the literary tradition that is lost. If you grow up thinking that John Green started YA, what parts of the conversation do you miss out on because of that? Book people find books, but there’s a whole hidden tradition there. I’ve been in the YA world for five years and it hadn’t occurred to me to revisit Paul Zindel until you messaged me.

A.S. King: I watched John’s most recent video this morning, and what I love about John is that he recommends books. He always recommends books, and I think it’s wonderful. I think he realizes that there is this huge responsibility on him because the media has said these things and he’s a huge influence on readers. And he’s very conscious of that. So I’m glad he recommends books. But when I read my students’ bibliographies, some of the books they come up with — a YA book from before the year of their birth, even if they’re fifty. And they always do. They never have a problem. So if I vlogged, which I don’t, but if I did, I would recommend Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. But then how would people find it?

Brenna: I would love to see him reissued.

A.S. King: They’re just fantastic books. All of them. And real.

When I was reading Zindel the first time, I remember writing down that when I grew up, I wanted to write books that would help adults understand teens better and help teens understand adults better. And I went home and I told my folks, and they suggested I could be a newspaper writer. As much as I respect newspaper writers, that wasn’t really what I had in mind. But then, only a few years ago, and it took me a few books to realize it: because I include adult characters, I’m doing that. And it’s wonderful. It’s kind of cool.

If I can cut down on the eye rolling when it comes to adults and teenagers, I’ve succeeded.

Here’s what I want to find out: how was Paul Zindel received? What were his reviews like? And who was he writing alongside? I would love to reconstruct YA from the early 1960s to the mid 1980s. But I’d need a clone. Or I need you to do it. One or the other.

But this stuff always existed. The darkness, or as I call it, life, has always existed. I just don’t think it’s changed that much.

But these are my thoughts: I’m a nUrdfighter. My daughter is a nerdfighter. And I love Paul Zindel.

Brenna: Ok, I’m going to just frame this up. You and I were talking on Twitter one day about Paul Zindel and his influence on YA and how he seems to be lost in the conversation about young adult literature.

A.S. King: At the moment, yeah. I mean, we have a lot of people like that, and there were people before that. Judy Blume, of course, and so many people even before that who I can’t name right now because it’s a little early in the morning! But Paul Zindel, for me, was my biggest influence. I was sort of a lost kid when I hit junior high school. I’d been this gifted kid who was doing advanced algebra and everything when I was in elementary school, and then when I got to junior high school I was bullied and it was all kinds of messed up. And then my education just fell. I went into basic math courses and they bored me.

So I found Paul Zindel thanks to my seventh grade teacher who assigned The Pigman, and I loved it. So I went to the library, and they had everything and I took it all. They no longer have everything because I stole it. And I’ve admitted this, and I’ve admitted it all over the country, and I know it’s a horrible thing, and I love librarians and work in my library. I feel horrible having done this and I will eventually pay back the Exeter Junior High School library. But I stole and continued to reread Paul Zindel, and Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, which is what I want to talk a little bit about today, is the one that really got me.

People ask how I get emotional detail into my books, and there’s this one scene I remembered vividly, even before I reread the book. This kid has to pee into a milk bottle. Because his mother is a travelling nurse, an in-home nurse, so they live in other people’s homes. And when the boy is in a room farther from the bathroom, she gives him a milk bottle to pee in. And I found this to be such a detail: the depth of what it must be, the humiliation that must come along with peeing in a milk bottle because your mom tells you you have to. And at his age, I think he’s about sixteen in the book. I’ve been talking about this for years, and that’s how I decided it was about time to pick up the book again.

I teach up at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and for my students’ bibliographies I always tell them, “You have to read a book written for young people before the date of your birth.” Now, obviously I was born before 1977 when Confessions of a Teenage Baboon was published, but what I found in this and in all of Zindel’s work is that adult characters reign. They reign in his books! In Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, even though Christopher Boyd is the narrator, the main characters are Lloyd Dipardi, an alcoholic depressive in his thirties; his mother, who’s dying; Christopher’s mother, who’s the nurse. And then there’s one other teen character and a few who come in and out. But the main characters are all adults. And the plot, especially towards the end (no spoilers!) is definitely about the adults, all seen through this kid’s eyes. Which is realistic!

Brenna: It is realistic, and it’s interesting, because one of the things that I like about your work is that the adult characters are these complex people who mess up, and their mess ups impact their kids. And that’s life, right? It’s really interesting to me how recent YA seems to often excise the parents, especially a lot of the really popular titles. Let’s have a convenient excuse to get the parents out of the picture. Boarding school is always really useful for that.

A.S. King: Exactly. And there’s certain things, like dystopia for example, where there’s a reason to get rid of all the parents. And I read pretty widely, so for the last few years as I’ve been stuck in my own book I’ve been reading a lot of surrealism, so I haven’t had my head in YA. But yes. What happened to me was that when I tried to sell Please Ignore Vera Dietz, I had editors who wanted to cut out the father’s voice and the flow charts. The idea was that teens only want to read about teens, and I can’t understand why anybody would box a group in like that. I know publishing is aiming towards a box and I understand that they’re trying to sell a product. But teenagers don’t fit into a box. Same as women don’t. Same as — none of us. We don’t.

So when I reread Paul Zindel’s work: wow. People always say to me, “Oh, you have all these adult characters and they’re really well-formed.” Well, yeah. Because my whole life was run by adults. I was the youngest in my family, so my sisters were even adults by the time I was a teenager. And then the coaches and the teachers — all these people were adults! So I couldn’t understand why there weren’t more books for teens that had adult characters. So it was great to go back to Zindel. Because he never flinched when it came to it. And I’ve always had adult characters in my books, even the unpublished ones, they’ve always been there. And I didn’t remember that in Zindel, but as I’m reading these books now I’m seeing just how much of his work influenced me long long long ago.

There was an article recently in the Boston Globe, if I’m correct — and I spoke to the author, who was lovely, and she recounted my experiences with the sale of Vera Dietz — but when she wrote the article she framed it as though adult characters are coming back in teen fiction. Which is probably true, based on what you said, a lot of recent work hasn’t had adults in it though mine always has. But I was writing adults in young adult fiction before I was a parent. None of that mattered. It mattered that my teen experience was run by adults. And I think every teen experience is.

Brenna: I think of it in terms of a trope that gets carried over from children’s literature. Because in children’s literature for middle grade and younger, you have to get rid of the parents so the characters can have that experience that takes them into experience. But I think fully formed adult characters are essential to young adult literature because those are the relationships that teenagers are trying to learn to negotiate. Most of them know how to talk to other teenagers. It’s adults who are frightening.

A.S. King: Absolutely. Because, I mean, when you look at the Hero’s Journey or any of these common ways of telling stories, you do have to get rid of the parents for younger readers. But even in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, Chris is truly changed by Lloyd. This is a heavy book. It isn’t a light book.

Brenna: And that’s something I want to come back to. When I was rereading Pigman on the plane on the way east I was thinking, wow, this whole notion that YA suddenly got dark in 2004 —

A.S. King: Yes! That’s what happened to me when I finished this book! I’m like, ok. First of all, Lloyd Disparti has a bottle of Wild Turkey in his hand from scene one.

Brenna: They’re all drunk! John is drunk all the time in The Pigman. That’s his character’s thing.

A.S. King: And in Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Edna talks about her mother being drunk all the time. These are drunk characters. And these are normal adults, let’s be fair. I look at the cross-section of adults I know, and, well.

But the darkness in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon: look, the mother is a hospice nurse, so we know there’s going to be an elderly person dying. But beyond that things get completely dark at the end of this book. That was the one surprise for me. I thought yeah, ok, adult characters, but I already knew adult characters had always existed. But the darkness was something I almost didn’t expect. Now I remembered the part scene at the end of The Pigman, and because my daughter took it from me and I couldn’t finish it, I haven’t revisited it. But I remember how it made me feel. And also the party scene at the end of Eyeball. So I know there’s a lot of confusion, darkness, all of that. And you’re absolutely right: it’s always been there.

Brenna: People are pretty good now about remembering to bring Judy Blume back into the conversation, but these other figures like Zindel have disappeared. We write about young adult fiction with this really ahistorical eye. Like, whatever’s happening right now is just what is.

A.S. King: But isn’t that what media is doing? When I left America, there was still news. I came back and now there isn’t news. It has turned into newsertainment. So it’s just such a different conversation. Everything has to be new and exciting so that people will watch and not turn the channel. And it’s the same with articles so that people won’t click out. But it is funny how we have reinvented what it means to be YA so that we can be aghast at what has always been.

I mean: Roald Dahl? Aren’t those two words that say dark right there? There’s a giant peach who runs over people and we loved it. We all cheered.

Brenna: I remember my cousin wasn’t allowed to read James and the Giant Peach because her mother thought it was way too violent and she was horrified that I was reading it. And now the idea of that just seems bizarre.

A.S. King: It is bizarre. But we do forget the history. Here’s one for you: when I was rereading Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, and I haven’t had time to research this so I’m just going to throw that out there, when Lloyd wants to insult Christopher, he calls him a nurd. Spelled with a U. So nerd, in 1977, in Paul Zindel’s head, was spelled N-U-R-D. For me, I felt that I could then identify. Paul Zindel saved my life. He really did. He made me feel normal when I was definitely having a hard time in junior high. So I’m a nUrdfighter with a U. And that’s no offence to the nerdfighters with an E. I think both would get along very very well. But it’s the idea that, you know, back then we didn’t have fandoms. I’m not hip on them now but we definitely didn’t have them then.

Brenna: Well you couldn’t connect with people outside of your world. If your friends weren’t reading the same books as you, your fandom was just you and the characters.

A.S. King: This was it. It was just me and Zindel’s characters. Which is part of the reason I took the books — I figured I might as well take them, since I was the only one reading them! (That’s a lie.) So there was no way to have that fandom. If I could create a fandom now for Paul Zindel books, I guess I really can’t steal nUrdfighter with the U, but that would be what I am. Because I realized that in 1982 and 1983, this was what I had. And the darkness didn’t even freak me out. I didn’t blink.

Brenna: I think I was much more disturbed by these books this time than when I read them when I was 13.

A.S. King: My heart is already breaking for Mr. Pignati and I’m not even half-way through rereading The Pigman yet. Because I remember and I know.

Rereading Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Marsh gives us his Hate List and Love List. And I kept a journal from the age of 15, and I did that in my journal. Every day I would have a list of things I loved and a list of things I hated. And that came from Paul Zindel. And in those, Marsh is hysterical about some of the adults in the book — he’s really open about them. But the first four chapters are dedicated to describing the adult characters, Marsh and Edna’s parents. There’s one scene with Edna’s parents in the psychologist’s office and they’re saying to the counsellor that they’ve done everything they can to make Edna acceptable: they’ve pinned her ears, bought these clothes, done this to her hair and nothing has worked because Edna doesn’t have any friends. And they want to know what they can do to get Edna a friend. Of course, Edna doesn’t really want any friends. But it’s the amazing scene that is there to colour Edna’s parents; it’s not really about Edna at all. And the same thing happens with Marsh’s parents right there in the beginning, and I think it’s wonderful.

One thing I find, and I think I have the best editor in the whole business, Andrea Spooner who is a genius, but I’ve worked with other editors as well — when you’re reading a book, or reviewing a book perhaps and that’s why editors have this idea — but people think you need to explain everything in the first fifty pages and it has to be centred toward the main character. And I don’t agree

Brenna: And Zindel definitely resists that.

A.S. King: This is it. For me, I’ve had editors who understand I might introduce a character on page 160. Because why not? That’s how life works. We’re sitting here right now, are we not? You were not introduced in the first fifty pages of my book but you are here. Right? It’s interesting.

When it comes to Zindel, I was really blown away by Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. I guess I really didn’t expect it to be that dark. And the end. This was a reminder that what I’m doing and what other people are doing isn’t new. This isn’t new. We have a history.

Brenna: I would love to see part of the YA powerhouse go back and republish some of these, because they’re hard to find. You can get Pigman on ebook anywhere, but the rest of the novels — if you don’t have an aging village library, you won’t find them. I don’t think you can find them new. If I’m wrong, someone on BookRiot will correct me on that, but Paul Zindel wrote like forty novels and they are not easy to find. The plays are easier, but the novels? No way.

A.S. King: The only thing I’ve found that would be frowned upon now, and rightly should be, is that in Confessions the character takes notice of one other character who is overweight. He takes notice, calling her Susan the Hippo, and he isn’t kind about her weight. Outside of that, though, there’s nothing here that wouldn’t fit into our contemporary culture. Plus, let’s face it, people do still think like that. I’m a big believer that until people stop thinking like that, we have to keep it in books. Plus it was written in 1977 and things were different then. The world wasn’t laced in high fructose corn syrup.

You know, it’s tough to constantly read that this person is the King of YA or the Queen of YA or Inventor of YA.

People might read my books and Paul Zindel’s books and say they’re not the same, because I have a character going through shock who experiences magical realism. But for me, having experienced shock a few times in my life, I don’t find that panicked daydream to be so unrealistic. How do you get through it otherwise? Rereading Zindel re-energized me, because it reminded me that there’s a huge history behind Young Adult. It’s not new. Because we now have it on a shelf we think it’s new. When I left America in the 1990s we didn’t have a shelf, and when I returned it was flying. But I didn’t know what it was.

I’ve always listed Paul Zindel as one of my influences. I just always have.

Brenna: I try to resist worrying about the future because I think the future usually takes care of itself, but I do wonder about the generation of writers who are going to come next. People will find books, because people who love books find books, but my concern is for the literary tradition that is lost. If you grow up thinking that John Green started YA, what parts of the conversation do you miss out on because of that? Book people find books, but there’s a whole hidden tradition there. I’ve been in the YA world for five years and it hadn’t occurred to me to revisit Paul Zindel until you messaged me.

A.S. King: I watched John’s most recent video this morning, and what I love about John is that he recommends books. He always recommends books, and I think it’s wonderful. I think he realizes that there is this huge responsibility on him because the media has said these things and he’s a huge influence on readers. And he’s very conscious of that. So I’m glad he recommends books. But when I read my students’ bibliographies, some of the books they come up with — a YA book from before the year of their birth, even if they’re fifty. And they always do. They never have a problem. So if I vlogged, which I don’t, but if I did, I would recommend Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. But then how would people find it?

Brenna: I would love to see him reissued.

A.S. King: They’re just fantastic books. All of them. And real.

When I was reading Zindel the first time, I remember writing down that when I grew up, I wanted to write books that would help adults understand teens better and help teens understand adults better. And I went home and I told my folks, and they suggested I could be a newspaper writer. As much as I respect newspaper writers, that wasn’t really what I had in mind. But then, only a few years ago, and it took me a few books to realize it: because I include adult characters, I’m doing that. And it’s wonderful. It’s kind of cool.

If I can cut down on the eye rolling when it comes to adults and teenagers, I’ve succeeded.

Here’s what I want to find out: how was Paul Zindel received? What were his reviews like? And who was he writing alongside? I would love to reconstruct YA from the early 1960s to the mid 1980s. But I’d need a clone. Or I need you to do it. One or the other.

But this stuff always existed. The darkness, or as I call it, life, has always existed. I just don’t think it’s changed that much.

But these are my thoughts: I’m a nUrdfighter. My daughter is a nerdfighter. And I love Paul Zindel.

Brenna: Ok, I’m going to just frame this up. You and I were talking on Twitter one day about Paul Zindel and his influence on YA and how he seems to be lost in the conversation about young adult literature.

A.S. King: At the moment, yeah. I mean, we have a lot of people like that, and there were people before that. Judy Blume, of course, and so many people even before that who I can’t name right now because it’s a little early in the morning! But Paul Zindel, for me, was my biggest influence. I was sort of a lost kid when I hit junior high school. I’d been this gifted kid who was doing advanced algebra and everything when I was in elementary school, and then when I got to junior high school I was bullied and it was all kinds of messed up. And then my education just fell. I went into basic math courses and they bored me.

So I found Paul Zindel thanks to my seventh grade teacher who assigned The Pigman, and I loved it. So I went to the library, and they had everything and I took it all. They no longer have everything because I stole it. And I’ve admitted this, and I’ve admitted it all over the country, and I know it’s a horrible thing, and I love librarians and work in my library. I feel horrible having done this and I will eventually pay back the Exeter Junior High School library. But I stole and continued to reread Paul Zindel, and Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, which is what I want to talk a little bit about today, is the one that really got me.

People ask how I get emotional detail into my books, and there’s this one scene I remembered vividly, even before I reread the book. This kid has to pee into a milk bottle. Because his mother is a travelling nurse, an in-home nurse, so they live in other people’s homes. And when the boy is in a room farther from the bathroom, she gives him a milk bottle to pee in. And I found this to be such a detail: the depth of what it must be, the humiliation that must come along with peeing in a milk bottle because your mom tells you you have to. And at his age, I think he’s about sixteen in the book. I’ve been talking about this for years, and that’s how I decided it was about time to pick up the book again.

I teach up at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and for my students’ bibliographies I always tell them, “You have to read a book written for young people before the date of your birth.” Now, obviously I was born before 1977 when Confessions of a Teenage Baboon was published, but what I found in this and in all of Zindel’s work is that adult characters reign. They reign in his books! In Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, even though Christopher Boyd is the narrator, the main characters are Lloyd Dipardi, an alcoholic depressive in his thirties; his mother, who’s dying; Christopher’s mother, who’s the nurse. And then there’s one other teen character and a few who come in and out. But the main characters are all adults. And the plot, especially towards the end (no spoilers!) is definitely about the adults, all seen through this kid’s eyes. Which is realistic!

Brenna: It is realistic, and it’s interesting, because one of the things that I like about your work is that the adult characters are these complex people who mess up, and their mess ups impact their kids. And that’s life, right? It’s really interesting to me how recent YA seems to often excise the parents, especially a lot of the really popular titles. Let’s have a convenient excuse to get the parents out of the picture. Boarding school is always really useful for that.

A.S. King: Exactly. And there’s certain things, like dystopia for example, where there’s a reason to get rid of all the parents. And I read pretty widely, so for the last few years as I’ve been stuck in my own book I’ve been reading a lot of surrealism, so I haven’t had my head in YA. But yes. What happened to me was that when I tried to sell Please Ignore Vera Dietz, I had editors who wanted to cut out the father’s voice and the flow charts. The idea was that teens only want to read about teens, and I can’t understand why anybody would box a group in like that. I know publishing is aiming towards a box and I understand that they’re trying to sell a product. But teenagers don’t fit into a box. Same as women don’t. Same as — none of us. We don’t.

So when I reread Paul Zindel’s work: wow. People always say to me, “Oh, you have all these adult characters and they’re really well-formed.” Well, yeah. Because my whole life was run by adults. I was the youngest in my family, so my sisters were even adults by the time I was a teenager. And then the coaches and the teachers — all these people were adults! So I couldn’t understand why there weren’t more books for teens that had adult characters. So it was great to go back to Zindel. Because he never flinched when it came to it. And I’ve always had adult characters in my books, even the unpublished ones, they’ve always been there. And I didn’t remember that in Zindel, but as I’m reading these books now I’m seeing just how much of his work influenced me long long long ago.

There was an article recently in the Boston Globe, if I’m correct — and I spoke to the author, who was lovely, and she recounted my experiences with the sale of Vera Dietz — but when she wrote the article she framed it as though adult characters are coming back in teen fiction. Which is probably true, based on what you said, a lot of recent work hasn’t had adults in it though mine always has. But I was writing adults in young adult fiction before I was a parent. None of that mattered. It mattered that my teen experience was run by adults. And I think every teen experience is.

Brenna: I think of it in terms of a trope that gets carried over from children’s literature. Because in children’s literature for middle grade and younger, you have to get rid of the parents so the characters can have that experience that takes them into experience. But I think fully formed adult characters are essential to young adult literature because those are the relationships that teenagers are trying to learn to negotiate. Most of them know how to talk to other teenagers. It’s adults who are frightening.

A.S. King: Absolutely. Because, I mean, when you look at the Hero’s Journey or any of these common ways of telling stories, you do have to get rid of the parents for younger readers. But even in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, Chris is truly changed by Lloyd. This is a heavy book. It isn’t a light book.

Brenna: And that’s something I want to come back to. When I was rereading Pigman on the plane on the way east I was thinking, wow, this whole notion that YA suddenly got dark in 2004 —

A.S. King: Yes! That’s what happened to me when I finished this book! I’m like, ok. First of all, Lloyd Disparti has a bottle of Wild Turkey in his hand from scene one.

Brenna: They’re all drunk! John is drunk all the time in The Pigman. That’s his character’s thing.

A.S. King: And in Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Edna talks about her mother being drunk all the time. These are drunk characters. And these are normal adults, let’s be fair. I look at the cross-section of adults I know, and, well.

But the darkness in Confessions of a Teenage Baboon: look, the mother is a hospice nurse, so we know there’s going to be an elderly person dying. But beyond that things get completely dark at the end of this book. That was the one surprise for me. I thought yeah, ok, adult characters, but I already knew adult characters had always existed. But the darkness was something I almost didn’t expect. Now I remembered the part scene at the end of The Pigman, and because my daughter took it from me and I couldn’t finish it, I haven’t revisited it. But I remember how it made me feel. And also the party scene at the end of Eyeball. So I know there’s a lot of confusion, darkness, all of that. And you’re absolutely right: it’s always been there.

Brenna: People are pretty good now about remembering to bring Judy Blume back into the conversation, but these other figures like Zindel have disappeared. We write about young adult fiction with this really ahistorical eye. Like, whatever’s happening right now is just what is.

A.S. King: But isn’t that what media is doing? When I left America, there was still news. I came back and now there isn’t news. It has turned into newsertainment. So it’s just such a different conversation. Everything has to be new and exciting so that people will watch and not turn the channel. And it’s the same with articles so that people won’t click out. But it is funny how we have reinvented what it means to be YA so that we can be aghast at what has always been.

I mean: Roald Dahl? Aren’t those two words that say dark right there? There’s a giant peach who runs over people and we loved it. We all cheered.

Brenna: I remember my cousin wasn’t allowed to read James and the Giant Peach because her mother thought it was way too violent and she was horrified that I was reading it. And now the idea of that just seems bizarre.

A.S. King: It is bizarre. But we do forget the history. Here’s one for you: when I was rereading Confessions of a Teenage Baboon, and I haven’t had time to research this so I’m just going to throw that out there, when Lloyd wants to insult Christopher, he calls him a nurd. Spelled with a U. So nerd, in 1977, in Paul Zindel’s head, was spelled N-U-R-D. For me, I felt that I could then identify. Paul Zindel saved my life. He really did. He made me feel normal when I was definitely having a hard time in junior high. So I’m a nUrdfighter with a U. And that’s no offence to the nerdfighters with an E. I think both would get along very very well. But it’s the idea that, you know, back then we didn’t have fandoms. I’m not hip on them now but we definitely didn’t have them then.

Brenna: Well you couldn’t connect with people outside of your world. If your friends weren’t reading the same books as you, your fandom was just you and the characters.

A.S. King: This was it. It was just me and Zindel’s characters. Which is part of the reason I took the books — I figured I might as well take them, since I was the only one reading them! (That’s a lie.) So there was no way to have that fandom. If I could create a fandom now for Paul Zindel books, I guess I really can’t steal nUrdfighter with the U, but that would be what I am. Because I realized that in 1982 and 1983, this was what I had. And the darkness didn’t even freak me out. I didn’t blink.

Brenna: I think I was much more disturbed by these books this time than when I read them when I was 13.

A.S. King: My heart is already breaking for Mr. Pignati and I’m not even half-way through rereading The Pigman yet. Because I remember and I know.

Rereading Pardon Me, You’re Stepping on My Eyeball, Marsh gives us his Hate List and Love List. And I kept a journal from the age of 15, and I did that in my journal. Every day I would have a list of things I loved and a list of things I hated. And that came from Paul Zindel. And in those, Marsh is hysterical about some of the adults in the book — he’s really open about them. But the first four chapters are dedicated to describing the adult characters, Marsh and Edna’s parents. There’s one scene with Edna’s parents in the psychologist’s office and they’re saying to the counsellor that they’ve done everything they can to make Edna acceptable: they’ve pinned her ears, bought these clothes, done this to her hair and nothing has worked because Edna doesn’t have any friends. And they want to know what they can do to get Edna a friend. Of course, Edna doesn’t really want any friends. But it’s the amazing scene that is there to colour Edna’s parents; it’s not really about Edna at all. And the same thing happens with Marsh’s parents right there in the beginning, and I think it’s wonderful.

One thing I find, and I think I have the best editor in the whole business, Andrea Spooner who is a genius, but I’ve worked with other editors as well — when you’re reading a book, or reviewing a book perhaps and that’s why editors have this idea — but people think you need to explain everything in the first fifty pages and it has to be centred toward the main character. And I don’t agree

Brenna: And Zindel definitely resists that.

A.S. King: This is it. For me, I’ve had editors who understand I might introduce a character on page 160. Because why not? That’s how life works. We’re sitting here right now, are we not? You were not introduced in the first fifty pages of my book but you are here. Right? It’s interesting.

When it comes to Zindel, I was really blown away by Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. I guess I really didn’t expect it to be that dark. And the end. This was a reminder that what I’m doing and what other people are doing isn’t new. This isn’t new. We have a history.

Brenna: I would love to see part of the YA powerhouse go back and republish some of these, because they’re hard to find. You can get Pigman on ebook anywhere, but the rest of the novels — if you don’t have an aging village library, you won’t find them. I don’t think you can find them new. If I’m wrong, someone on BookRiot will correct me on that, but Paul Zindel wrote like forty novels and they are not easy to find. The plays are easier, but the novels? No way.

A.S. King: The only thing I’ve found that would be frowned upon now, and rightly should be, is that in Confessions the character takes notice of one other character who is overweight. He takes notice, calling her Susan the Hippo, and he isn’t kind about her weight. Outside of that, though, there’s nothing here that wouldn’t fit into our contemporary culture. Plus, let’s face it, people do still think like that. I’m a big believer that until people stop thinking like that, we have to keep it in books. Plus it was written in 1977 and things were different then. The world wasn’t laced in high fructose corn syrup.

You know, it’s tough to constantly read that this person is the King of YA or the Queen of YA or Inventor of YA.

People might read my books and Paul Zindel’s books and say they’re not the same, because I have a character going through shock who experiences magical realism. But for me, having experienced shock a few times in my life, I don’t find that panicked daydream to be so unrealistic. How do you get through it otherwise? Rereading Zindel re-energized me, because it reminded me that there’s a huge history behind Young Adult. It’s not new. Because we now have it on a shelf we think it’s new. When I left America in the 1990s we didn’t have a shelf, and when I returned it was flying. But I didn’t know what it was.

I’ve always listed Paul Zindel as one of my influences. I just always have.

Brenna: I try to resist worrying about the future because I think the future usually takes care of itself, but I do wonder about the generation of writers who are going to come next. People will find books, because people who love books find books, but my concern is for the literary tradition that is lost. If you grow up thinking that John Green started YA, what parts of the conversation do you miss out on because of that? Book people find books, but there’s a whole hidden tradition there. I’ve been in the YA world for five years and it hadn’t occurred to me to revisit Paul Zindel until you messaged me.

A.S. King: I watched John’s most recent video this morning, and what I love about John is that he recommends books. He always recommends books, and I think it’s wonderful. I think he realizes that there is this huge responsibility on him because the media has said these things and he’s a huge influence on readers. And he’s very conscious of that. So I’m glad he recommends books. But when I read my students’ bibliographies, some of the books they come up with — a YA book from before the year of their birth, even if they’re fifty. And they always do. They never have a problem. So if I vlogged, which I don’t, but if I did, I would recommend Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. But then how would people find it?

Brenna: I would love to see him reissued.

A.S. King: They’re just fantastic books. All of them. And real.

When I was reading Zindel the first time, I remember writing down that when I grew up, I wanted to write books that would help adults understand teens better and help teens understand adults better. And I went home and I told my folks, and they suggested I could be a newspaper writer. As much as I respect newspaper writers, that wasn’t really what I had in mind. But then, only a few years ago, and it took me a few books to realize it: because I include adult characters, I’m doing that. And it’s wonderful. It’s kind of cool.

If I can cut down on the eye rolling when it comes to adults and teenagers, I’ve succeeded.

Here’s what I want to find out: how was Paul Zindel received? What were his reviews like? And who was he writing alongside? I would love to reconstruct YA from the early 1960s to the mid 1980s. But I’d need a clone. Or I need you to do it. One or the other.

But this stuff always existed. The darkness, or as I call it, life, has always existed. I just don’t think it’s changed that much.

But these are my thoughts: I’m a nUrdfighter. My daughter is a nerdfighter. And I love Paul Zindel.