The Narrative Magic of Picture Books: An Interview with Mac Barnett

If you don’t think picture books can be considered literary fiction, that Harold and the Purple Crayon is strictly child’s play, then a few minutes with Mac Barnett may change your mind. The author (whose works include Chloe and the Lion and Extra Yarn) speaks passionately about his craft and has strong opinions about the power and potential of children’s literature. After hearing him at a recent picture book panel in DC (where he held court on everything from metafiction to skeomorphism), I decided to track him down for a few questions.

Q: You’ve described picture books as coming from a tradition of experimentation. What is it about the form that makes it particularly conducive to experimental fiction?

Mac Barnett: Picture books are stories told with image and text, and the best books exploit that relationship to engage the reader, emotionally or intellectually. In a bad book, the pictures just illustrate what the text is already telling you. “Johnny woke up early,” the first page will say, next to a picture of a boy stretching as the sun rises outside his window. That’s redundant. But when the pictures amplify the text, or contradict the text, or tell a story the text doesn’t address—that’s how you make narrative magic. You can tell rich, complex—but still comprehensible—narratives in picture books; and really the form sort of demands that you do.

Q: So, you’re trying to convince a skeptic and they ask you for one example that really shows off the narrative potential of the picture book–which one do you give them?

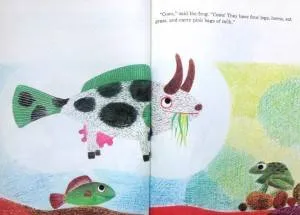

MB: Maybe Fish is Fish, which I think is Leo Lionni’s masterpiece. The book is full of astonishing moments and brilliant picture book craft. It’s the story of a minnow who befriends a tadpole. The tadpole becomes a frog and leaves the pond to explore land. The book’s middle section details an episode where the frog returns to tell the fish about what he’s seen. The text conveys the frog’s story, while the illustrations show the fish’s imaginings, which are constrained by his fishness. Check out this spread, where the frog tells the fish about cows:

Mac Barnett: Picture books are stories told with image and text, and the best books exploit that relationship to engage the reader, emotionally or intellectually. In a bad book, the pictures just illustrate what the text is already telling you. “Johnny woke up early,” the first page will say, next to a picture of a boy stretching as the sun rises outside his window. That’s redundant. But when the pictures amplify the text, or contradict the text, or tell a story the text doesn’t address—that’s how you make narrative magic. You can tell rich, complex—but still comprehensible—narratives in picture books; and really the form sort of demands that you do.

Q: So, you’re trying to convince a skeptic and they ask you for one example that really shows off the narrative potential of the picture book–which one do you give them?

MB: Maybe Fish is Fish, which I think is Leo Lionni’s masterpiece. The book is full of astonishing moments and brilliant picture book craft. It’s the story of a minnow who befriends a tadpole. The tadpole becomes a frog and leaves the pond to explore land. The book’s middle section details an episode where the frog returns to tell the fish about what he’s seen. The text conveys the frog’s story, while the illustrations show the fish’s imaginings, which are constrained by his fishness. Check out this spread, where the frog tells the fish about cows:

It’s funny and beautiful and profound, and you couldn’t do it with just words (or just pictures, for that matter).

Q: In Chloe and the Lion, you and Adam Rex riff on the author/illustrator relationship. But seriously, as an author is it ever difficult to relinquish some of the control over your story? (Please feel free to include any examples of conflict involving fisticuffs and/or duels at dawn.)

MB: You know, I really don’t find it hard to hand a text over to an illustrator, and that’s probably because I don’t think of a picture book as my story. When a picture book works, the artist is responsible for at least 50% of the storytelling, and often more. If I finish a manuscript and it makes perfect sense without illustrations, I’ve failed. A lot of the narrative lifting done by a novelist—physical description most obviously, but there’s more—is done by the artist in a picture book.

Q: In 2011, you penned a Picture Book Proclamation to spur conversation about the state of children’s literature. Has the landscape changed much since then?

MB: My sense has been that people are starting to take picture books more seriously as an art form. Or at least some people are. I think we reached a low point in 2010, when picture books were being slagged off on the front page of The New York Times and dismissed by publishing house’s accounting departments. And I hate to see picture books trashed or, worse, dismissed because there’s so much great and beautiful stuff coming out each year. Of course, there are a lot of bad books too—so many that sometimes I think it can create the illusion that the form is hidebound or imitative or insincere. But that is an illusion.

Q: Recently, when someone asked about advice for aspiring picture book authors, you said “Read. A lot. And not just picture books. Read everything.” Do you have any go-to books/authors that you reach for whenever you want some inspiration?

MB: Gogol, Kafka, Russell Hoban, Louise Fitzhugh, Ellen Raskin, David Foster Wallace, James Marshall, Tomi Ungerer, Chris Ware, George Saunders.

Q: You actually had the chance to study with David Foster Wallace—are there lessons from your time with him that still show up in your work today?

MB: Oh, sure. Studying with Wallace changed the way I wrote in all sorts of ways. One big way: Dave emphasized fiction as a means of communication, and talked all the time about the writer’s obligation to engage the reader. He was interested in rhetoric, in ways to get the reader to go along with you, but there was an ethical dimension to the position he advocated: If you are asking readers to understand you, you have a responsibility to give them something in return.

Those stakes are maybe even more immediate in picture books. Picture books are a true popular art form: for all that freedom to experiment, there’s also an obligation to entertain, to capture a kid’s attention. If we fail, if we’re boring, that kid may not take a gamble on literary fiction again. Plus when children’s writers mess up, it’s usually an adult—a parent or teacher or librarian or babysitter—who’s on the hook for our mistakes.

It’s funny and beautiful and profound, and you couldn’t do it with just words (or just pictures, for that matter).

Q: In Chloe and the Lion, you and Adam Rex riff on the author/illustrator relationship. But seriously, as an author is it ever difficult to relinquish some of the control over your story? (Please feel free to include any examples of conflict involving fisticuffs and/or duels at dawn.)

MB: You know, I really don’t find it hard to hand a text over to an illustrator, and that’s probably because I don’t think of a picture book as my story. When a picture book works, the artist is responsible for at least 50% of the storytelling, and often more. If I finish a manuscript and it makes perfect sense without illustrations, I’ve failed. A lot of the narrative lifting done by a novelist—physical description most obviously, but there’s more—is done by the artist in a picture book.

Q: In 2011, you penned a Picture Book Proclamation to spur conversation about the state of children’s literature. Has the landscape changed much since then?

MB: My sense has been that people are starting to take picture books more seriously as an art form. Or at least some people are. I think we reached a low point in 2010, when picture books were being slagged off on the front page of The New York Times and dismissed by publishing house’s accounting departments. And I hate to see picture books trashed or, worse, dismissed because there’s so much great and beautiful stuff coming out each year. Of course, there are a lot of bad books too—so many that sometimes I think it can create the illusion that the form is hidebound or imitative or insincere. But that is an illusion.

Q: Recently, when someone asked about advice for aspiring picture book authors, you said “Read. A lot. And not just picture books. Read everything.” Do you have any go-to books/authors that you reach for whenever you want some inspiration?

MB: Gogol, Kafka, Russell Hoban, Louise Fitzhugh, Ellen Raskin, David Foster Wallace, James Marshall, Tomi Ungerer, Chris Ware, George Saunders.

Q: You actually had the chance to study with David Foster Wallace—are there lessons from your time with him that still show up in your work today?

MB: Oh, sure. Studying with Wallace changed the way I wrote in all sorts of ways. One big way: Dave emphasized fiction as a means of communication, and talked all the time about the writer’s obligation to engage the reader. He was interested in rhetoric, in ways to get the reader to go along with you, but there was an ethical dimension to the position he advocated: If you are asking readers to understand you, you have a responsibility to give them something in return.

Those stakes are maybe even more immediate in picture books. Picture books are a true popular art form: for all that freedom to experiment, there’s also an obligation to entertain, to capture a kid’s attention. If we fail, if we’re boring, that kid may not take a gamble on literary fiction again. Plus when children’s writers mess up, it’s usually an adult—a parent or teacher or librarian or babysitter—who’s on the hook for our mistakes.

One Last Random Q: You were the director of 826LA and the Echo Park Time Travel Mart for a while. Since you had privileged access to time travel supplies, if you went back in time (leaving behind all scruples and/or morals, of course) to steal the idea for one book, which one would it be? And how can we be sure that you haven’t already done this?

MB: The last book I read and said, “I wish I’d done this!” was It’s a Secret! by John Burningham. But that came out in 2009, which means I’d have to go back to 2008 to steal it, and that doesn’t sound very appealing—it wasn’t a great year.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.

One Last Random Q: You were the director of 826LA and the Echo Park Time Travel Mart for a while. Since you had privileged access to time travel supplies, if you went back in time (leaving behind all scruples and/or morals, of course) to steal the idea for one book, which one would it be? And how can we be sure that you haven’t already done this?

MB: The last book I read and said, “I wish I’d done this!” was It’s a Secret! by John Burningham. But that came out in 2009, which means I’d have to go back to 2008 to steal it, and that doesn’t sound very appealing—it wasn’t a great year.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.

Mac Barnett: Picture books are stories told with image and text, and the best books exploit that relationship to engage the reader, emotionally or intellectually. In a bad book, the pictures just illustrate what the text is already telling you. “Johnny woke up early,” the first page will say, next to a picture of a boy stretching as the sun rises outside his window. That’s redundant. But when the pictures amplify the text, or contradict the text, or tell a story the text doesn’t address—that’s how you make narrative magic. You can tell rich, complex—but still comprehensible—narratives in picture books; and really the form sort of demands that you do.

Q: So, you’re trying to convince a skeptic and they ask you for one example that really shows off the narrative potential of the picture book–which one do you give them?

MB: Maybe Fish is Fish, which I think is Leo Lionni’s masterpiece. The book is full of astonishing moments and brilliant picture book craft. It’s the story of a minnow who befriends a tadpole. The tadpole becomes a frog and leaves the pond to explore land. The book’s middle section details an episode where the frog returns to tell the fish about what he’s seen. The text conveys the frog’s story, while the illustrations show the fish’s imaginings, which are constrained by his fishness. Check out this spread, where the frog tells the fish about cows:

Mac Barnett: Picture books are stories told with image and text, and the best books exploit that relationship to engage the reader, emotionally or intellectually. In a bad book, the pictures just illustrate what the text is already telling you. “Johnny woke up early,” the first page will say, next to a picture of a boy stretching as the sun rises outside his window. That’s redundant. But when the pictures amplify the text, or contradict the text, or tell a story the text doesn’t address—that’s how you make narrative magic. You can tell rich, complex—but still comprehensible—narratives in picture books; and really the form sort of demands that you do.

Q: So, you’re trying to convince a skeptic and they ask you for one example that really shows off the narrative potential of the picture book–which one do you give them?

MB: Maybe Fish is Fish, which I think is Leo Lionni’s masterpiece. The book is full of astonishing moments and brilliant picture book craft. It’s the story of a minnow who befriends a tadpole. The tadpole becomes a frog and leaves the pond to explore land. The book’s middle section details an episode where the frog returns to tell the fish about what he’s seen. The text conveys the frog’s story, while the illustrations show the fish’s imaginings, which are constrained by his fishness. Check out this spread, where the frog tells the fish about cows:

It’s funny and beautiful and profound, and you couldn’t do it with just words (or just pictures, for that matter).

Q: In Chloe and the Lion, you and Adam Rex riff on the author/illustrator relationship. But seriously, as an author is it ever difficult to relinquish some of the control over your story? (Please feel free to include any examples of conflict involving fisticuffs and/or duels at dawn.)

MB: You know, I really don’t find it hard to hand a text over to an illustrator, and that’s probably because I don’t think of a picture book as my story. When a picture book works, the artist is responsible for at least 50% of the storytelling, and often more. If I finish a manuscript and it makes perfect sense without illustrations, I’ve failed. A lot of the narrative lifting done by a novelist—physical description most obviously, but there’s more—is done by the artist in a picture book.

Q: In 2011, you penned a Picture Book Proclamation to spur conversation about the state of children’s literature. Has the landscape changed much since then?

MB: My sense has been that people are starting to take picture books more seriously as an art form. Or at least some people are. I think we reached a low point in 2010, when picture books were being slagged off on the front page of The New York Times and dismissed by publishing house’s accounting departments. And I hate to see picture books trashed or, worse, dismissed because there’s so much great and beautiful stuff coming out each year. Of course, there are a lot of bad books too—so many that sometimes I think it can create the illusion that the form is hidebound or imitative or insincere. But that is an illusion.

Q: Recently, when someone asked about advice for aspiring picture book authors, you said “Read. A lot. And not just picture books. Read everything.” Do you have any go-to books/authors that you reach for whenever you want some inspiration?

MB: Gogol, Kafka, Russell Hoban, Louise Fitzhugh, Ellen Raskin, David Foster Wallace, James Marshall, Tomi Ungerer, Chris Ware, George Saunders.

Q: You actually had the chance to study with David Foster Wallace—are there lessons from your time with him that still show up in your work today?

MB: Oh, sure. Studying with Wallace changed the way I wrote in all sorts of ways. One big way: Dave emphasized fiction as a means of communication, and talked all the time about the writer’s obligation to engage the reader. He was interested in rhetoric, in ways to get the reader to go along with you, but there was an ethical dimension to the position he advocated: If you are asking readers to understand you, you have a responsibility to give them something in return.

Those stakes are maybe even more immediate in picture books. Picture books are a true popular art form: for all that freedom to experiment, there’s also an obligation to entertain, to capture a kid’s attention. If we fail, if we’re boring, that kid may not take a gamble on literary fiction again. Plus when children’s writers mess up, it’s usually an adult—a parent or teacher or librarian or babysitter—who’s on the hook for our mistakes.

It’s funny and beautiful and profound, and you couldn’t do it with just words (or just pictures, for that matter).

Q: In Chloe and the Lion, you and Adam Rex riff on the author/illustrator relationship. But seriously, as an author is it ever difficult to relinquish some of the control over your story? (Please feel free to include any examples of conflict involving fisticuffs and/or duels at dawn.)

MB: You know, I really don’t find it hard to hand a text over to an illustrator, and that’s probably because I don’t think of a picture book as my story. When a picture book works, the artist is responsible for at least 50% of the storytelling, and often more. If I finish a manuscript and it makes perfect sense without illustrations, I’ve failed. A lot of the narrative lifting done by a novelist—physical description most obviously, but there’s more—is done by the artist in a picture book.

Q: In 2011, you penned a Picture Book Proclamation to spur conversation about the state of children’s literature. Has the landscape changed much since then?

MB: My sense has been that people are starting to take picture books more seriously as an art form. Or at least some people are. I think we reached a low point in 2010, when picture books were being slagged off on the front page of The New York Times and dismissed by publishing house’s accounting departments. And I hate to see picture books trashed or, worse, dismissed because there’s so much great and beautiful stuff coming out each year. Of course, there are a lot of bad books too—so many that sometimes I think it can create the illusion that the form is hidebound or imitative or insincere. But that is an illusion.

Q: Recently, when someone asked about advice for aspiring picture book authors, you said “Read. A lot. And not just picture books. Read everything.” Do you have any go-to books/authors that you reach for whenever you want some inspiration?

MB: Gogol, Kafka, Russell Hoban, Louise Fitzhugh, Ellen Raskin, David Foster Wallace, James Marshall, Tomi Ungerer, Chris Ware, George Saunders.

Q: You actually had the chance to study with David Foster Wallace—are there lessons from your time with him that still show up in your work today?

MB: Oh, sure. Studying with Wallace changed the way I wrote in all sorts of ways. One big way: Dave emphasized fiction as a means of communication, and talked all the time about the writer’s obligation to engage the reader. He was interested in rhetoric, in ways to get the reader to go along with you, but there was an ethical dimension to the position he advocated: If you are asking readers to understand you, you have a responsibility to give them something in return.

Those stakes are maybe even more immediate in picture books. Picture books are a true popular art form: for all that freedom to experiment, there’s also an obligation to entertain, to capture a kid’s attention. If we fail, if we’re boring, that kid may not take a gamble on literary fiction again. Plus when children’s writers mess up, it’s usually an adult—a parent or teacher or librarian or babysitter—who’s on the hook for our mistakes.

One Last Random Q: You were the director of 826LA and the Echo Park Time Travel Mart for a while. Since you had privileged access to time travel supplies, if you went back in time (leaving behind all scruples and/or morals, of course) to steal the idea for one book, which one would it be? And how can we be sure that you haven’t already done this?

MB: The last book I read and said, “I wish I’d done this!” was It’s a Secret! by John Burningham. But that came out in 2009, which means I’d have to go back to 2008 to steal it, and that doesn’t sound very appealing—it wasn’t a great year.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.

One Last Random Q: You were the director of 826LA and the Echo Park Time Travel Mart for a while. Since you had privileged access to time travel supplies, if you went back in time (leaving behind all scruples and/or morals, of course) to steal the idea for one book, which one would it be? And how can we be sure that you haven’t already done this?

MB: The last book I read and said, “I wish I’d done this!” was It’s a Secret! by John Burningham. But that came out in 2009, which means I’d have to go back to 2008 to steal it, and that doesn’t sound very appealing—it wasn’t a great year.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.