What Murder Mysteries Get Wrong (and Right) about Wills

For fans of Agatha Christie and other mystery writers, wills — and trusts to a lesser extent — come up a lot in plots. Greed and jealousy prove extremely good motives for murder. Who inherits, who does not, and any conditions of the will can create endless reasons for one character to off another. Or characters find themselves in unusual positions thanks to conditions of a will or trust.

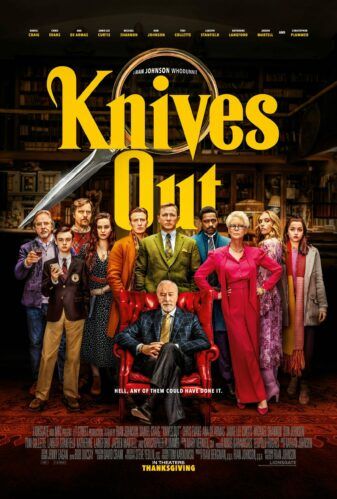

Of course, most mystery movie enthusiasts are probably familiar with the central role that a will played in the movie Knives Out. Audiences were confronted with questions about undue influence, slayer statutes, and generalities about writing the will.

But how much do mysteries get right and wrong about the laws around wills and trusts? How easy is it to change a will? I reached out to two attorneys and did a lot of research to separate fact from fiction. The first attorney is Tami Kamin Meyer, lawyer and freelance writer in Columbus, OH, and the second is Leslie Karst, a former lawyer and author behind the Sally Solari Mystery Series and recently published Justice is Served: A Tale of Scallops, the Law, and Cooking for RBG.

It’s important to note that this article is focusing on the present day United States. Kamin Meyer also pointed out that “As far as amendments, state laws govern wills and estates. So, that is 50 sets of laws.” Some things may be legal in some states but not others.

Not a Performance

Thanks to movies like Knives Out and Agatha Christie novels, one common misconception is that wills are not read aloud, Karst pointed out. “There is never a ‘reading’ of the Will. That’s ridiculous,” explained Benjamin Ivory, Attorney at Law | The Law Office of Kelly, Kelly, & Kelly, LLC.

Typically, a will itself is often a private document until it is filed. Then it’s in the court record (unless there is a reason for it to be sealed, like if it involves a minor), Karst said. Someone may have to reach out to the beneficiaries, but Karst thinks that’s more likely done through email these days.

Anthony S. Park, attorney at Anthony S. Park, PLLC, theorized that the reading of a will may have been something from the past. He wrote: “Reading of the will may have been more common in times past. When literacy rates were low, reading a document had its purpose. So too did gathering everyone together at one time.” Maybe that’s why it was so common in Agatha Christie novels!

But fiction does take liberties with the law. Having everyone gathered together for a reading means that all the possible suspects are together in one room. Plus, it’s a nice way to build tension and drama as people find out if they inherit or not.

When There is a Will, There is a Way

Having someone change a will is a common plot point in many books, whether it’s preventing someone from being written out of the will or adding someone. Or in one book that shall remain nameless, the murderer killed someone before a law went into effect since it would impact their ability to inherit.

So how easy is it to make a will in the first place? Actually it’s not that hard, so that rings true. In the state of California, Karst pointed out there are two basic types of wills. The first is a holographic will, which is handwritten and signed by the testator (the person who signs the will). However, not all states recognize such a will. The second, which is probably more common, is printed either by computer or typewriter. This one needs to be signed by the testator and two witnesses, who watched the signing, and then signed it themselves. But Karst points out that people tend to use attorneys because they fear messing something up, which makes sense.

Amending or changing a will can be done by writing it from scratch or having an addition called a codicil. But what a testator can do depends on the state. Kamin Meyer said, “Some states allow it; some states don’t. Some states require an entire will to be rewritten.”

But can you disinherit someone like a spouse or a child? Again, it depends on the state. Kamin Meyer, who practices in Ohio, pointed out that in Ohio: “a spouse cannot write their spouse out of their will. Children, yes. Spouse, no.” However, someone may be able to establish a trust to get around it but that’s a whole other article! So while it’s a great motive for murder, you might want to check the state to see if it’s legal or not!

Time is Money

Oftentimes, the time between death and the heirs receiving their inheritance is really quick. But wills have to go through probate and that takes time. Kamin Meyer said, “the average is about nine months. It could take several years. It depends if there’s anyone who contests the will.”

And anyone can technically contest a will, she noted. “Will contests arise for as many possible reasons as there are people,” Kamin Meyer noted. In her experience, which is not scientific, about one in three wills are contested. In those cases, it can take years for the will to be settled. Testators can put in clauses saying that people who contest the will lose their right to inheritance.

Once again, the reason that mysteries may speed up the process is again for dramatic effect. Many mysteries take place over a few days, weeks, and months. Waiting years for a will to settle in probate court might drag out a story unnecessarily.

For Good Reason

Once again, there are many reasons that mysteries may not get all the particulars right. Karst said “I think that’s partly because mystery authors know that they probably don’t know the law, so they’re leery of putting anything definite down.” Leaving it vague is one way of doing it.

Another is that the law is not exactly as fast-paced and exciting as it is in fiction. “Too much legal stuff is boring. The law ultimately is really very detailed if you read these statutes,” Karst said. “Explaining to the reader the details of the legality of a will or not, a lot of people’s eyes would glaze over.”

And finally, Karst pointed out one sobering fact: “Working in probate and trust and estate law is really depressing. Because it’s families bickering over money when a loved one has just died.” So while we can watch fictional people squabble over an inheritance, it’s something completely different to watch it in real life.

Want more discussion of fact and fiction in mysteries? Here’s a discussion about what mysteries get wrong about the law (in general). And if you want more thoughts on the roles that wills and testaments play in mysteries, check out this post.