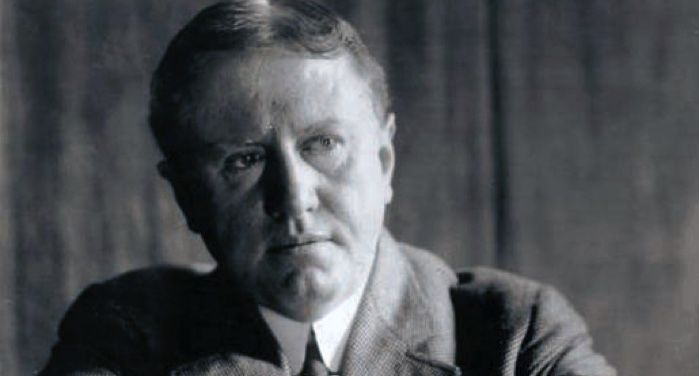

The Life and Wild Times of O. Henry

Every few years, a revelation about some classic author or other sends shock waves through the literary community. Agatha Christie went missing for 11 days and no one is really sure what happened? Henry David Thoreau lived walking distance from town, threw frequent parties, and his mother did his laundry? Mary Shelley lost her virginity on her mother’s grave? That sort of thing. And while this story perhaps isn’t quite at that level, it is nonetheless consuming my every thought right now.

Known for his charming stories with surprise endings, including “The Gift of the Magi” and “The Last Leaf,” it should be no surprise that O. Henry’s life had some twists of its own life. When I went off in search of some biographical information, I half-expected to learn something distasteful, such as “he was from money and had no idea what it’s like to not be able to afford a Christmas gift for your beloved spouse!” or “he never experienced illness or the death of a loved one and had no idea what it would be like to try to keep someone alive!” but instead I found a complex man with a sometimes sad, sometimes bananapants life. Buckle up, it’s going to be a bumpy post.

Born William Sidney Porter (he later changed his middle name to Sydney) on September 11, 1862, Henry’s mother died when he was 3 years old and he and his physician father moved in with his grandmother. He read voraciously, particularly loving the Edward William Lane translation of The Thousand and One Nights. He graduated elementary school and was tutored by an aunt until her death. Then he became licensed as a pharmacist in 1881 at the age of 19. He developed a persistent cough and moved to Texas, where he worked as a sheep rancher for his friend Richard Hall. His health improved in the southern air.

He and Hall moved to Austin, where he went back to working as a pharmacist. Henry met Athol Estes there, and they eloped in 1885 when her parents did not approve of the marriage due to her tuberculosis. They had a son who died at birth in 1888 and a daughter, Margaret, in 1889.

Here’s where things start to get bonkers.

Hall became the Texas Land Commissioner in 1887 and offered Henry a job in the General Land Office (GLO). Hall then ran for Governor in 1890 and lost; as Henry’s position was appointed, he resigned when the winner, Jim Hogg, was sworn in. He found a job at the First National Bank of Austin, which was “informally run.” For the same salary he’d earned at GLO ($100 a month), he worked as a teller and bookkeeper. He was apparently not a very good bookkeeper (see above, re: informal) and after three years or so was accused of embezzling funds and fired, but not formally charged.

Around the same time, Henry started a humorous weekly called The Rolling Stone, which topped out at 1500 subscribers and was generally considered successful. After he was fired from First National, he worked on the periodical full-time until it went under the following year due to lack of funds. (It could be noted that there is a tremendous coincidence between his shady bookkeeping at the bank and his starting the paper, and then his firing from the bank and the paper running out of money. Someone probably noticed that, is all I am saying.)

The editor of the Houston Post had noticed Henry’s writing and drawings in The Rolling Stone, and offered him a job, so the family moved to Houston in 1895 and he worked for a reduced salary of $25 a month, though this amount increased as his popularity among readers did.

And then the feds audited First National, found the very discrepancies that had led to Henry’s firing, and indicted him on charges of embezzlement. I told you this was a rollercoaster!

Athol’s father posted bail, and on July 6, 1896 (my birthday! Minus 80-odd years!), the day before he was due to stand trial, Henry was changing trains en route to the courthouse when he suddenly lost his nerve and ran. To Central America. Honduras, to be specific. He lived there for six months, during which time he befriended notorious train robber Al Jennings (what) who later wrote a book about their friendship. (WHAT.) He also wrote his book Cabbages and Kings while there, in which he coined the phrase “banana republic” to describe Honduras. Thanks but no thanks, dude.

Athol and Margaret, who were staying with her parents, were supposed to join Henry in exile, but she became too ill to travel. Henry returned to Texas in February 1897 and turned himself in. Athol died in July, and he stood trial the following winter. On February 17, 1898, he was found guilty of embezzling $854.08 (he apparently did not speak in his own defense at trial). He was sentenced to five years in prison and sent to the Ohio State Penitentiary. It is believed that he spent no time in general population, as his pharmacist’s license qualified him for a job as the night druggist and he was given a room in the hospital wing.

It was at this time that he began to use O. Henry as a pseudonym. He had 14 stories published during his time in prison, sending them to a friend in New Orleans to send on to publishers so that his incarceration would not be known. He was released in 1901 for good behavior, and reunited with Margaret, now 11 years old, in Pittsburgh where the Estes family had relocated.

In 1902, Henry moved to New York City and had his most prolific period of publication. He wrote a breathtaking 381 stories there, including a story a week for over a year for the New York World Sunday Magazine.

Henry remarried in 1907 after a visit to North Carolina reunited him with a childhood friend, Sarah Lindsey Coleman, whose fictionalized account of their courtship is in her novel Winds of Destiny. Their marriage lasted only two years, likely due to his heavy drinking and the deterioration of his health as a result of it. He died of cirrhosis of the liver, among other conditions, in 1910.

It is now believed by many that he was innocent of the embezzlement charges, a fact that he always maintained. In 2012 the USPS issued an O. Henry stamp and Barack Obama quoted Henry when he pardoned the Thanksgiving turkeys. The same year, Texas Attorney Scott Henson and political science professor P.S. Ruckman Jr. filed an application for a posthumous pardon. President Obama did not grant the request, which remains ungranted.

Sources:

- North Carolina History

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica

- and ye olde Wikipedia