What is Prose Poetry?

If you just looked at the title of this article with utter confusion, you’re not alone. At first glance, prose and poetry seem like opposites, things that just cannot go together. In fact, prose poetry is its own form of poetry and possibly, a special form of prose. So what is prose poetry?

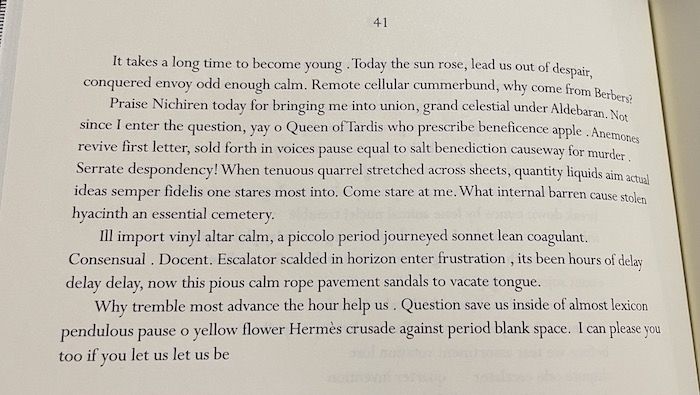

In the most basic sense, prose poetry is poetry without line breaks. That is to say, each line ends when it touches the right margin on the page, naturally flowing down to the next line. This might seem like the poet has decided to just ignore the many uses of line breaks such as end stops and enjambment. This is poetry, however, so every decision is purposeful.

Emphasis

Line breaks are used to create emphasis. A word that ends a line or stands on its own line will inevitably have more emphasis. There’s a moment when the eye travels down and to the left, to the next line, when that last word lives in your mind just a little longer. Prose poetry eschews this, flattening the emphasis of each word and line.

Why do this? Imagine the difference between a person recounting a tragic event with all sorts of hand gestures, whispers, screams, and general drama. Now imagine that same recounting done in monotone, staring at a fire with barely-repressed grief tinging every word. The latter example is something prose poetry can do, delivering even the most impassioned words with dispassionate disconnect.

Ambiguity

Choosing the prose poetry form makes purposeful ambiguity a harder tool to wield. With line breaks, a line can appear to mean one thing based on the end word, and then the next line can recontextualize it.

Now as you read prose poetry, you may think, “I still see line breaks. Can’t the poet play with those to create ambiguity?” My answer is: maybe. If you’re reading a poetry book from one particular poet, then they have more freedom to play with margins and fonts. In a book like Tyehimba Jess’s Olio, the poet’s influence over the exact size and shape of the book is obvious. Others are less so. However, poets often have their work published in literary journals long before collecting them into books. As a poet, you don’t have control over margins, page size, font, or font size. So when a prose poem is published in one of these journals, it will likely look different from your word processing document.

It’s also not really prose poetry if there’s any control over line length. That’s just a concrete poem, a poem made to be a particular shape.

Tempo and Energy

Line length, end stops, and enjambments have a big effect on the tempo and energy of a poem. Lots of short lines with no end stops feels quick, energetic, like the poet is moving you from thought to thought with all due haste. Or like with Ginsberg’s “Howl,” those long lines, too long for any page, aren’t fast, but they have a relentlessness to them.

Prose poetry invites itself to a prose-like reading pace, however, giving some control of tempo and energy to the reader. Not all of the control, though. In fact, the consistent and uncontrolled line lengths actually give more power to spacing, punctuation, and word choice in terms of tempo and energy.

Is It Really Poetry?

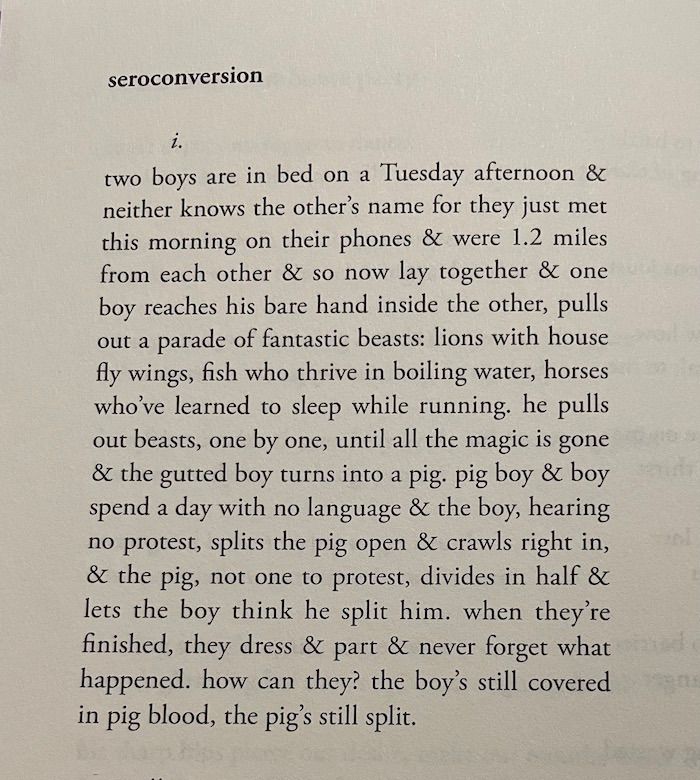

There are debates in some academic circles about the overlap between prose poetry and microfiction. Microfiction is generally defined as a story told in 1,000 or fewer words. That’s just four pages of standard 12 point, double-spaced typing.

But one is a poem and the other is fiction? How can they be the same?

In order to tell an effective story in under 1,000 words, every sentence and word needs to be scrutinized. Compression must win the day when crafting a story with a beginning, middle, and end, full of great characterization and dramatic tension, in just four pages. Compression always has to win the day in poetry. Poets are always looking for the most effective noun or verb to do as much work as possible with each syllable, whether in prose poetry or sonnets or no form at all.

Recently, prose poems and microfiction have shared panel time at literary conferences. Fiction and poetry professors have been working together on classes that combine these two forms, seeing the benefits that poets and fiction writers can teach each other. The combination is quite remarkable.

The next time you’re reading a poetry book and find something that look like prose, maybe it is. It’s also poetry. Read it as such and know that yes, there is a reason the poet chose that form.