Victorian Era Science: On Geology, George Eliot, and More

Of course, the Victorian era science was about more than steampunk or Maggie Smith in mauve! The Victorian era saw The Birth of Modern Science. TRA-LA! (And yes, questionable corsetry. Read about it in Ruth Goodman‘s wonderful How To Be A Victorian.)

On The Origins of Species was published in 1859. Natural history was in its heyday. Charles Darwin’s beard was growing! The Galapagos finch beaks were evolving! Times, they were a-changin’!

Charles Darwin, rock star.

In Reading The Rocks: How Victorian Geologists Discovered The Secret of Life biographer Brenda Maddox, author of George Eliot in Love, focuses on the rock stars of Victorian era science. Like, the actual rocks. Meet the Blue Lias. Meet Lyme Regis. And the early geologists who studied rock strata like a historical layer cake of Life on Earth.

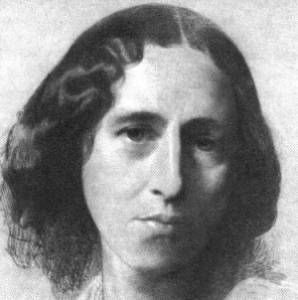

You’ve got your Darwin, your Lyell, your Sedgwick. However, George Eliot was also involved. In addition to being a literary giant, she was an amateur natural historian. Whatta gal.

George Eliot, rock hound.

Compared to astronomy, geology was a young Victorian era science. Geologizing was new and considered a wholesome activity for the whole family. Ditto seashell collecting. Also butterfly collecting. And fern collecting. A good Victorian filled a Wardian case or wunderkammer to the brim with bric-a-brac they’d collected.

The Atlantic’s science writer Ed Yong has written that 19th-century naturalists like Charles Darwin collected beetles for sport, “and eagerly compared the size of their collections.” A-hem.

Likewise, “It is necessary to have a cabinet of curiosities,” is something Oscar Wilde could have said.

Brenda Maddox, channelling the witty Wilde, pens epigrams in Reading The Rocks. She writes, “In the 1830s, geology was more than new: it was fashionable.” BLAM. “Many drawings of early geologists at work make a top hat seem as essential as a hammer.” ZING.

The DAWN OF THE GeoLOGICAL SOCIETY

What was it like to be an early member of Britain’s Geological Society? Founded 1807, it is the oldest geological society in the world. So, you know, no big deal. They were just figuring out how mountains were formed.

Maddox writes that GeolSoc (pronounced jocularly, “jelsock”) in the 1830s was SO fun. It was a thriving boys-only club for gentlemen of means. They clashed and and joshed over rocks and the precise dates of Noachian flood.

However, they quickly realized, bup bup bup, hey now, Sir Roger, the world is waaaaay older than that of the Bible. Boyz, by studying rock strata and fossils, we’ve gotten ourselves smack dab into religion vs. empirical science woozle! This will last well into the 20th century! The luck! And we’ve done it in top hats! Huzzah!

VICTORIAN ERA WOMEN IN SCIENCE: MARY ANNING

An aside: Lyme Regis, part of England’s “Jurassic Coast,” is also the territory of Tracey Chevalier’s Remarkable Creatures. (Nineteenth-century literature and #STEM fans, if you haven’t read this book, get your bustle on. Get to know early paleontologist and fossil finder Mary Anning and her little dog Tray.)

Mary Anning, rock god.

Anning discovered one of the most significant geological finds of all time: the first-ever ichthyosaur.

Anning gets a hat tip Reading The Rocks. However, the door to Science was closed to women in the Victorian era and shut tight to working class women like Anning. Anning scraped and toiled for the work of her learned, male contemporaries, William Buckland, Henry de la Beche and William Conybeare.

ROMANCING THE STONES: ViCTORIAN ERA SCIENCE AND GEORGE ELIOT

Reading Reading The Rocks you’ll want to put on straw bonnet and chisel ammonites out of the rock. You want to ask some questions about Deep Time.

In fact, George Eliot mused on such with her sweetheart George Henry Lewes, author Sea-side Studies at Ilfracombe, Tenby, the Scilly Isles, and Jersey.

Maddox writes, “Together the pair spent many days scouring the coastal rocks around Britain, collecting marine fossils, classifying them, and storing them in glass jars.” Swoon. Be still my heart, you lovebirds!

The Victorian era science of geology was highly romantic.

Maddox charms with the story of how William Buckland (1784–1856), “one of the greatest geologists of his time,” met his future wife Mary Morland, “while traveling by coach to Dorset.”

“He was reading a heavy tome by Cuvier and saw a woman passenger reading the exact same book. On speaking to her he was surprised to find that she had worked as an illustrator on the book…They were married by the end of the year and spent a geological honeymoon inspecting caves in France and Sicily.”

You know what your love life is missing? Inspecting French caves. Victorian era science. Top hat and rock chisel and “geological honeymoon.” Get your rocks on.