Scraped Knees and Boyish Hair: The Tomboy in Literature

This is a guest post from Megan Mayhew-Bergman. Megan lives on a small farm in Vermont, where she is a Justice of the Peace and mother of two. Scribner published her first book, Birds of a Lesser Paradise, which was a Huffington Post Best Book of 2012 and a Barnes and Noble Discover Pick. Scribner will also publish her second collection, Almost Famous Women, on January 6, 2105, and a forthcoming novel. Follow her on Twitter @mayhewbergman.

____________________

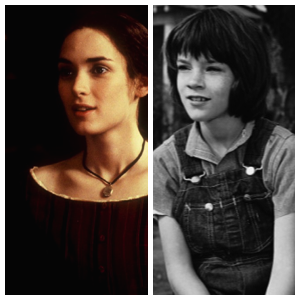

I was always drawn to the tomboys in fiction, girls with cropped hair, grass-stained pants, and short tempers. The early books I fed myself on were Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Nancy Drew. Later I idolized Turtle Wexler, the shin-kicking, stock-obsessed 13 year-old in Ellen Raskin’s The Westing Game, and Harper Lee’s Scout Finch and Carson McCullers’ Mick Kelly, the young protagonist of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. While reading some of these books to my daughter, I was immediately struck by the gravitational pull these characters had on me as a child, and the way they influenced me as both a woman and a writer.

Little Women came first, as a gorgeous volume underneath the Christmas tree. I knew it was special, the kind of book you held onto for the rest of your life, and I secreted it away, stashing it in a wooden cabinet close to my bed. I read and re-read it, focusing on the sections about Jo and her precious notebooks full of writing, and the moment when she boldly decides to cut off her hair. The reader can’t help but be drawn to Jo; she’s a woman of action, ideals, and endearing flaws. I could feel her potential as a human being—if only the world would get out of her way.

Jo March, during a particularly grumpy monologue, cries, “It’s bad enough to be a girl, anyway, when I like boys’ games and work and manners! I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy; and it’s worse than ever now, for I’m dying to go and fight with papa, and I can only stay at home and knit, like a poky old woman!” To be fair, I don’t aspire to fight, and I love knitting and other traditionally feminine, poky pursuits: cooking, gardening, antiquing. I don’t so much want to be a boy as I want to be free from expectations about traditional femininity and the messages society throws my way: clean your house, tend your children while your husband pursues his dreams, be gentle and beautiful, don’t age. I don’t think Jo resents being a girl as much as being treated like one; she resents her lack of agency, the sense of helplessness that permeates her work and home life.

The Oxford English Dictionary once associated tomboys with “rudeness and impropriety.” But as a shy, sensitive, and insecure girl, I wanted those traits in my toolbox, maybe even needed them as coping mechanisms. I felt fascinated by tomboyish outbursts, because they were inherent displays of individuality and power, two traits I felt I sorely lacked in my southern adolescence. I was bowled over by honesty such as Jo’s:

Jo immediately sat up, put her hands in her pockets, and began to whistle.

“Don’t, Jo; it’s so boyish!”

“That’s why I do it.”

“I detest rude, unlady-like girls!”

“I hate affected, niminy-piminy chits!”

To me, the “tomboy” has enviable mobility, the option of moving between gendered activities, and the permission to be honest about her wants and desires. Jo wants to write and earn money, but still likes a good party and gossiping with her sisters. Nancy Drew and her best friend George go dancing with their boyfriends, but they also take physical risks, chasing “prowlers” down dark streets and inside haunted mansions, scaling fences, sailing boats, taking Nancy’s blue convertible on a high-speed chase. (Okay, maybe a medium-speed chase.) There is, I believe, evidence of the animus in tomboyish characters in fiction, the unconscious masculine personality asserting itself. I sensed this early on, and admired it, later recognizing a desire to honor it in my characters and in myself.

It’s hard to talk about tomboys without bringing up the contemporary issue of female protagonists and likeability, a conversation I usually find reductive. I’m not a reader who needs to “like” a protagonist—what I’m more drawn to as an adult reader is complexity, awareness, and emotional honesty, energy on the page. When I look back to how my earliest sensibilities as a reader were constructed, I inevitably think of the tomboys I loved. I train my eye on the complex, dream-pursuing woman, not the chit.

It is, then, no surprise that I fell hard for Beryl Markham’s memoir West with the Night, a lyrical (potentially ghost-written) tale of an airplane-flying, horse-training woman in slacks, a woman Hemingway called a “high-grade bitch.” Though Beryl had her share of love and loss, romantic pursuits were almost entirely absent from her memoir. While I wouldn’t want to put my emotional life in her hands, I would want to have a beer with her. She may not have been nurturing or a master of domestic arts, but she possessed undeniable strength, courage, complexity, and passion. What shocks me most is that her memoir still reads as unusual today—the female protagonist as non-romantic hero of her own story. Literature needs more Cheryl Strayeds and Linda Greenlaws, courageous women living large in life and on the page.

The tomboy protagonist is often a projection of the author herself, a semi-autobiographical stand-in as in the case of Harper Lee and Scout, and Alcott and Jo. I have found myself doing the same, hoping and dreaming with my pen, trying to live on the page in a way I can’t quite live in the world, and aspiring to close that gap. What I have learned as a reader and a writer: the so-called tomboy—scuffing her shoes down a dirt road, the wind in her pixie-cut—shapes a girl’s sense of possibility.

____________________

Follow us on Tumblr for for book recs, literary talk, and the occasional pic of a puppy reading.