Who Gets To Be the Final Girl In Horror Novels and Movies?

Horror cinema has always had the capacity to push against structures of power. In the book Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan, Robin Wood identifies how horror movies have situations where “normality is threatened by the monster.” Whether the normality is a group of friends in a cabin, a family on vacation, or the expectation that you won’t encounter a supernatural monster, horror upends the expectation.

The Final Girl is a particular formation of slasher horror films where a woman would unexpectedly survive until the end of a horror story. The Final Girl was officially defined by Charlotte Clover in 1987 in her essay “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film.” Clover describes, “She alone looks death in the face; but she alone also finds the strength either to stay the killer long enough to be rescued (ending A) or to kill him herself (ending B).”

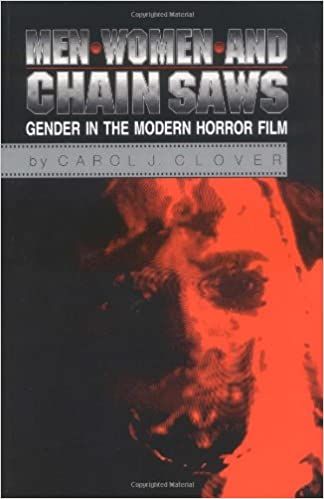

She expanded the definition in 1992 in her definitive text on the matter: Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Though horror films were generally believed to be the domain of men and male viewers —especially with the horror exploitation genre that generally wreaked havoc upon female bodies — Clover pointed out the canon of women surviving the slasher genre and killing the killer.

The original definition of the Final Girl focuses on a small slate of movies: slasher films from the 1970s and 1980s where cis white women survive to the end and triumph. Some of the original canonical Final Girls are Sally Hardesty in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974, directed by Tobe Hooper), Laurie Strode in Halloween (1978, directed by John Carpenter), Nancy Thompson in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984, directed by Wes Craven), and Ellen Ripley in Alien (1979, directed by Ridley Scott).

What’s the similarity? They’re all white. Ripley is the major standout, but the general idea of the original Final Girl is that she is white, often blonde, a virgin, and resourceful in a way those around her are not. The question then becomes: who gets to be the Final Girl in horror novels and movies now?

Women in Horror and Final Girls

I spoke to horror film expert Lauren La Melle, host of the Scary Crit podcast, about the Final Girl trope. Her answer to why the Final Girl is historically white: “Why is any film or television character white? It’s a byproduct of society and who is making media.” All the directors who helped to define our view of the original Final Girls are white men. Halloween is the only film of the original set with a female co-writer credited (Debra Hill).

According to Lauren, Scream (1996, directed by Wes Craven) was the first major critique of the Final Girl with Sidney Prescott, played by Neve Campbell. Since the movie directly interrogated the Final Girl ideology that Wes Craven had a hand in starting, Sidney very deliberately was not a virgin and got more hardened and less innocent as the movie went along. The Scream sequels that followed Sidney continued to unpack what it would mean to continue with your life after these tragedies. Sidney’s major role was to upend the status quo in slashers, leading to a new confrontation with normality.

Future of Final Girls

For horror fans, the Final Girl can still be a figure of resistance and aspiration. In an article about the Final Girl and the possible new form of her in the movie The Witch (2015, directed by Robert Eggers), Mary Beth McAndrews writes, “The Final Girl has been the perfect figure to articulate the gender politics of the horror genre as she reflects societal ideas of what a female character should be and tries to break through them.”

Lauren of Scary Crit mentioned Terrifier (2016, directed by Damien Leone) as another new Final Girl because of the darkness of the film. However, she also questioned the state of the modern slasher and how the new vision of the Final Girl will come from that: “Where is the new boogeyman hiding in our closets with an eight-inch blade ready to strike? Is that the weapon anymore? Are they still in the closet? For a fresh take on a trope, we need a fresh set of circumstances, and that’s what I’m waiting to see on screen.”

For horror novelists, the trope of Final Girl is fertile ground for reimagining horror. The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix, Final Girls by Riley Sager, and The Last Final Girl by Stephen Graham Jones are all books full of references to and critiques of the Final Girl trope, that also put the characters through the horror of a slasher.

You’re Not Supposed to Die Tonight by Kalynn Bayron is an upcoming Final Girl trope interrogation novel with a Black queer protagonist, which is still a major departure from the established trope. Horror novels attack the stasis of normality in the same way that horror cinema does, so it only makes sense for the occupant of the Final Girl role to be as far from her cis, white origins as possible. Not to sound crass, but a white girl who survives a horror story is now ubiquitous enough to be normal and boring.

Another future strand of the Final Girl could be the rapidly developing “Good For Her” cinematic and literary universe. Though not all are strictly Final Girls, they represent a way of the horror heroine taking back the power proactively, as opposed to fighting the slasher killer reactively.

Why does the Final Girl still matter?

The Final Girl still matters because horror reflects what society currently finds repulsive or too upsetting to talk about. In the 1970s slashers, teens were out on the road, having sex, and otherwise “misbehaving,” so they were punished by an egomaniacal killer who represented neo-conservatism beating back the counter-culture that had taken root in the 1960s. There are tons of other valid interpretations of the slasher apart from that, though.

It matters that people of color and queer people make it to the end of a horror story, and new stories are coming out that upend the Final Girl trope. Two movies from this past year, Barbarian (directed by Zach Cregger) and The Invitation (directed by Jessica M. Thompson), show progress in how people of color are represented by including Black female protagonists. Horror novels are also a major source for new stories that subvert the trope because books have slightly fewer barriers than producing large-scale Hollywood films do. In this time of constant optioning of books for future movies, maybe the horror novels are going to tell us where the Final Girl will go.

For more horror goodness, you can find the best horror books, young adult horror written by women, and horror by authors of color.