When Did the Butler Dunnit? The History of “the Butler Did It” Trope

If you’re a reader of mysteries or even fancy a whodunit murder mystery movie at the end of a long day, you’ve likely heard of the trope “the butler did it.” It conjures images of a butler, darting around an isolated mansion unnoticed, spinning up some revenge plot or plan to escape with his rich employer’s millions. This type of plot is often seen as cheap or predictable, an easy out for a closed-room murder or heist. But where did the trope come from, and how common is it, really?

When the Butler First Did It

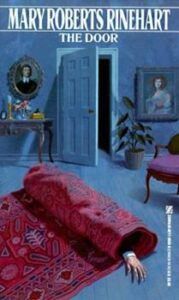

According to numerous sources, “the butler did it” trope was coined by Mary Roberts Rinehart in The Door, a 1930s mystery by the prolific author in which, well, the butler does it. In the novel, an elderly family nurse was murdered, and the revealed suspect isn’t confirmed until the very last page. Interestingly enough, though Rinehart is credited with the expression “the butler did it,” the phrase doesn’t appear in The Door, nor was she the first to use that plot device.

In fact, in 1930 when it came out, it was already seen as a weak and predictable plot in the public eye. In a review in Life in 1926, according to an analysis of the trope by Gareth Rees, a reviewer of The Donovan Affair said “we automatically suspect the butler right at the start” and a character in “What, No Butler?” by Damon Runyon in 1933 says the “way these things are done in all the murder-mystery movies and plays” is to pin it on the butler.

A much-quoted rule for mysteries by S.S. Van Dine, an American art critic and detective novel writer, railed against choosing a servant as the culprit as a “too easy solution” in his list of “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories” from 1928.

How Popular Was the Trope, Really?

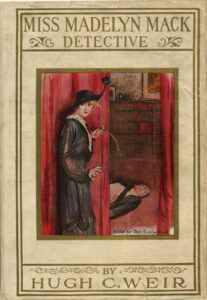

As it turns out, the trope was not that popular, despite how much people poke at the possibility of the butler brandishing the butter knife. In 1893, “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual” by Arthur Conan Doyle features a criminal butler, though not the main suspect; in 1914, “The Man with Nine Lives” by Hugh C. Weir featured a criminal butler; and in 1915, E. Philips Oppenheim wrote The Black Box, in which a criminal masquerading as a British butler murders a girl for the family jewels. Agatha Christie, too, took on the butler finger-pointing in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd in 1926, though this is a red herring in the novel and no actual butler-doing-it was done.

But really, there weren’t that many novels or stories that used the trope, especially not enough to garner the public’s eye-rolling at the use of it in 1930. Mike Grost said The Door was “notable for being one of only a few real-life examples” of the trope.

So, how can Rinehart be the creator of the trope if people were already cracking jokes or offering criticisms about it by the time her novel even came out? And how can it be so popular if not many novels even used the trope?

Where’s the Popularity Coming From, if Not Books?

Rees proposes the source is actually silent films, listing 16 that had butlers that did it or were suspected of doing a crime between 1915 and 1922, which could explain the public being familiar with, and subsequently sighing over, the trope in later literature. If you’ve seen it over a dozen times over on screen, it’s no wonder reading it yet again in a supposedly mysterious murder mystery wouldn’t feel so shocking.

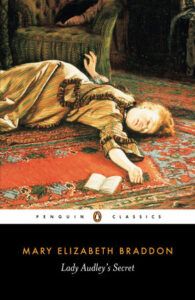

TV Tropes posits it may have to do with societal fears in reality, a playing up of the upper class’s suspicion of their domestic servants having sticky fingers in their own household. In volume four of London Labour and the London Poor published in 1851 by Henry Mayhew, the chapter on “housebreakers and burglars” says it “occasionally happens servants are in league with thieves,” detailing the ways in which criminals can manipulate or work with the servants of the household to gain access to its hidden riches. In Lady Audley’s Secret from 1862, too, the character Lady Audley “shares with her Victorian readers a mounting anxiety about the eyes and ears of servants in the home.” It makes a certain sense that the trope seemed more popular because it dug into the fears of the upper class at the time.

Whether you like the old butler-did-it trope or could do without it, hopefully, you found this glimpse into the trope’s history interesting. If you’re in the mood for a whodunit (don’t worry, no spoilers on the who), check out these locked room mysteries or this quiz that will match you with your next whodunit read!