The Best Cars of American Fiction

This is a guest post from Andy Browers. Andy believes in going to State Fairs, road trips, fist-pumping at wedding receptions to rock and roll, all you can eat sushi, and doing it all with a book in your hand. He writes blogs and essays from Minneapolis, MN.

____________________

Americans are troublemakers. Let me explain.

I draw wisdom from The Music Man with extreme reluctance—just ask any of my friends who I’ve subjected to my abridged version of the entire musical, which takes only four seconds and one dance move resembling grotesque old-timey clogging.

But sometimes you have to turn to The Music Man.

It has a lot to say on the topic of trouble. Playwright Meredith Wilson assures us “it’s the model T Ford made the trouble,” not unlike the kind that eventually found its way to River City, Iowa with a capital T that rhymes with P that stands for lots of things, including plays I hope to never see again.

So, back to trouble.

Who made the Model T Ford and all that followed in the first place? Americans. Americans did. We love trouble, which is to say we love cars.

Like Mr. Toad of Toad Hall—who also got into trouble because of them, am I right?—our American fanaticism for automobiles was instant and consuming. Cars filled our avenues, our conversations, our dreams for over a hundred and twenty-five years, so of course tons of writers have given them a place in their books.

The showroom of the best cars found in those books could be huge and cluttered, so I’ve left out some that probably deserve to be included. I narrowed it down to domestic models only, so you won’t find any Chitty Chitty Bang Bangs or Aston Martins, I’m afraid. Sorry Brit Lit—maybe next time. Because it’s a neat number, tidy and balanced, I’ve picked out three of my favorites for us to spin around the block.

So, in no particular order.

While writing Travels With Charley, Steinbeck meets and mediates on the newly minted culture of the mobile home, which he sees as being perfectly matched for the restless American spirit. We can live on the road. On the road! And he does, too, in his tricked-out-for-its-time camper, which he named Rocinante after Don Quixote’s horse with the woeful countenance. Whenever he felt like it, he could eat, sleep, entertain, and drink right from the comfort (used loosely in this case, probably) of his vehicle. And drink he does. Before setting out, he hits up a liquor store for so much booze to take along that the clerk assumes he’s throwing a huge party.

Maybe he was. Maybe it was a welcome home party. Maybe he felt the urge to live like a turtle—the spirit animal of The Millennials, perhaps—and to carry your home on your back because in the shifting sands of our culture and circumstances, you might never find another one. Americans move a lot now, changing careers often and following jobs as hunters follow herds. And like John Steinbeck as he penned this book on the tiny table deep inside Rocinante, we tend to find the idea of working from home really appealing.

It’s not much to look at, that camper truck. You can find out for yourself, of course, at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, where it sits on display. It may get overshadowed by literature’s flashier makes and models, but if you’re looking for substance over style, Rocinante is the car for you.

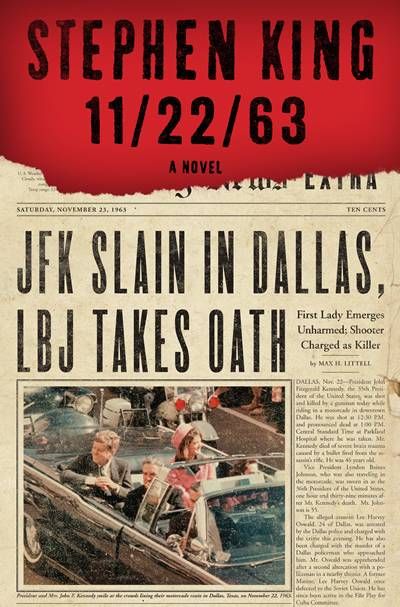

Two chapters. It takes two chapters.

Once Jake/King gets his dream car, it’s not hard to imagine either of them sneaking out to the garage at midnight to gaze lovingly at their beautiful machine. The author veils his love for the car so thinly that you can basically hear the smile in his words whenever he writes about it. It shares some traits with King’s writing style itself: sometimes overlarge; built from common, All-American parts; dependable; and with its fins over the taillights and candy-colored paintjob, it’s got just enough flair to let you know it’s supposed to be fun. Oh, and you can also bet it’s filled with rock and roll.

The Sunliner doesn’t get to be the feature of the story like the terrifying, sentient vehicles of Christine and Maximum Overdrive or get the attention of the Buick 8, but it’s an iconic heart, pumping as much Bradburian wonder for what Stephen King calls the “Land of Ago” as it can—which is a lot.

Nothing lasts forever, and when the Sunliner has driven its last mile in the novel, the parting stings a little. As he buys a new set of wheels out of necessity, Jake confesses the Sunliner was the first car he ever really loved. First love? The subject of a great story? WHAT?

You might have fond childhood memories of your family’s car. Mine are of a rockin’ 1980s station wagon complete with wood panels and a supercool I (HEART) 4-H bumper sticker. It came to represent everything we were: a unit of quiet nerds waiting our turn to ride in the coveted “way way back,” where you could make a nest and nap or watch the world and your thoughts pass by backwards. For literary car number three, we’re going way way back to substance over style, and we’re going back to Steinbeck.

The novel isn’t shy about its metaphors. With Steinbeck, is a car ever just a car? Of course not. It also gets heavily featured on the dust jackets and paperback covers of several editions, which smacks a bit of importance.

I’m not shy about metaphors either: families are a little like sharks, I think. I don’t mean in the sense of their savagery or excessive sets of chompers waiting to sink into your vulnerable parts (or do I?), but in the sense of without forward motion—true dynamics—they die.

The dreams of the Joad family come about as close to death as one can get. They suffer setbacks, they take on stray passengers, they break down. Without the luxury of trading yours in for a newer, faster, safer make or model you have to learn how a family gets fixed while you’re on the road and you pretty much have to do it yourself. The other alternative is to walk alone—a bleak and impossible option for a farmer fleeing the suffocating terror of the Dust Bowl and a bleak and impossible option for a modern anybody trying to flee the suffocating terror of insignificance. It’s a compelling image to climb up onto.

I’m not even especially a car person; I’m licensed to operate one, but that’s about where my relationship with them mostly ends. That writers have enchanted me with their imagined automobiles and all they represent speaks to the power of both the writer and their subject.

Whether we read for comfort or for speed, we’ll keep finding cars in our books. And, if you’re like me, you’ll keep finding books in your car.