Why It’s Time to Stop Talking About Jack the Ripper

In the past few weeks, two notable Jack The Ripper–related stories made the news. One was the latest claim that the serial killer’s identity had been finally solved (spoiler: it hasn’t been). The second was a viral Twitter discussion of how and why the Ripper murders are covered in school curriculum—making a game of the murders, and treating the female victims as corpses, rather than people.

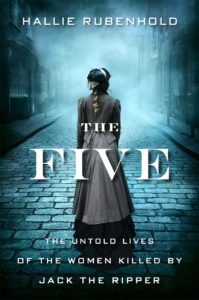

While we will never know the identity of their murderer, Rubenhold works to ensure that we learn more than just the names of his five canonical victims: Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols (age 43), Annie Chapman (age 47), Elizabeth Stride (age 44), Catherine Eddowes (age 46) and Mary Jane Kelly (25).

In her book, Rubenhold pieces together who these women were, using census records and other archival materials to learn who they were and how each wound up alone at night in Whitechapel. In so doing, the author reveals much about what life may have been like for many lower-class women in 19th-century London. Then as now, a culture of misogyny combined with lack of compassion for addiction and mental health issues kept these five women effectively trapped in a cycle of poverty.

Part of the infamy of Jack The Ripper is the frenzied way that contemporary news media covered the crimes. Photographs of the death scenes and morgue photos made the five women the most famous corpses in London. Their humanity was seemingly never in question: as lower-class women murdered in Whitechapel under cover of darkness, the widespread assumption was they had been sex workers.

Culturally, then as now, this meant that the mainstream population could easily dismiss them as being somehow less than human to begin with. Part of Rubenhold’s book explores each of the women’s connection to sex work (her findings suggest that two of the five were active in the industry at the time of their deaths), but never uses this as an excuse for us to ignore their humanity. By focusing her narrative on the women’s lives, sidelining the murders themselves, Rubenhold reminds us all that these women were much more than just ready-made victims.

Countless books have been and will continue to be published that claim to solve the mystery of Jack the Ripper’s identity. With this new work, Rubenhold dares us to change the conversation. We will never know who Jack was, but we do know the names, ages, and many details about these five women. The time is ripe to bring a similar approach to other notorious murderers—setting aside the motivations and manifestos of murderers, and respecting the victims by saying their names and learning their stories.