Ecce Homo: Sex and the Passion in Tiffany Reisz’s THE PRINCE

Trigger Warning: Discussions of rape follow.

Earlier this year I started a little project of rereading Tiffany Reisz’s Original Sinners series with the intention of taking a critical look at Reisz’s use of theology and biblical reference throughout the eight book series. My plan was to write one long essay on the topic that tried to identify a series wide pattern. But about three books into the note taking process, two things happened:

1. I realized that this was going to be WAY too much information for a single essay.

2. I stumbled across something in The Prince (book 3) that had escaped my notice in previous rereadings of the series, and it made my nerd brain light up like a Lite-Brite.

Before I get started: there’s no way to break down the two scenes I’ll be discussing without spoilers. So if you haven’t read the Original Sinners series yet, caveat lector.

Series Summary

Series Summary

In brief, the Original Sinners is an erotic romance series with a vast cast of characters, but most of the plot revolves around three central figures: Nora Sutherlin, an erotica writer and professional dominatrix; Kingsley Edge, an ex-spy and the king of the series’ BDSM underground; and Søren, shadow king of the underground, consummate sadist, and priest. Reisz and her fans call these three “the unholy trinity” (though I’m not sure who coined the term), and that’s not just a tongue in cheek reference to Søren’s profession. Over the course of the series the three of them do, in fact, come to embody the figures of the trinity, sometimes interchangeably.

The scene in The Prince that I want to pull apart and look at in detail takes place between Søren and Kingsley, at a moment when King is very much standing in the role of Christ. However, in order to understand both the scene and its significance to the larger series, I need to start with a brief moment from the first book of the series, The Siren.

Ecce Homo

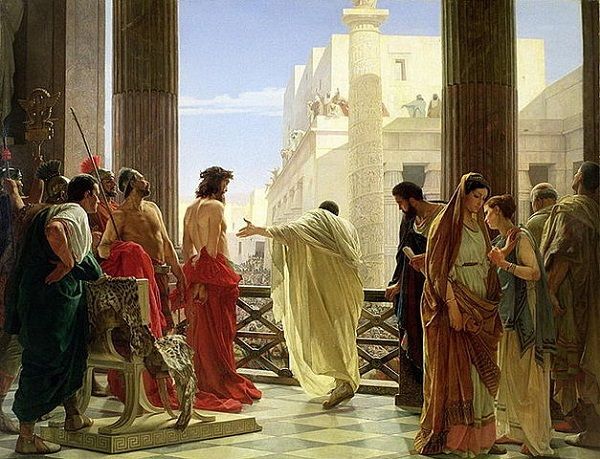

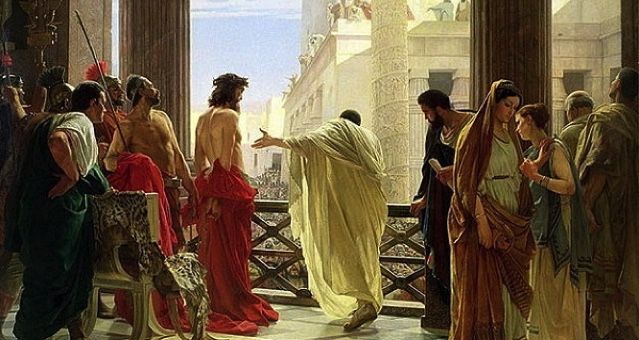

In The Siren, Nora introduces her editor Zach Easton to a reproduction of Antonio Ciseri’s painting Ecce Homo, which hangs in her (and Søren’s) church. During the ensuing conversation, readers are given two important pieces of information: a description of what Nora calls “Søren’s impressively twisted theology of the trinity”:

“God the Father inflicted the suffering and humiliation, God the Son submitted to it willingly and God the Holy Spirit gave Christ the grace to endure it.” (120)

and an analysis of Ciseri’s painting that both illustrates Søren’s theology and foreshadows the scene form The Prince that I will be discussing.

I have always loved sacred art. It ranges from the beautiful to the gruesome, and sometimes manages to be both at the same time. Depictions of the Passion in particular fit into either or both of these categories, depending on the artist’s interpretation. The painting by Ciseri (above), for example, prefers beauty. Though the scene of the scourging technically calls for blood and physical wounding, Christ’s body here is depicted as untouched. As Nora explains to Zach, “Ciseri is emphasizing Christ’s beauty, not His beating” (121). She goes on to point out that it’s not very accurate, but then most depictions of the crucifixion aren’t technically accurate because they always show Christ partially clothed. But in fact victims of the crucifixion were always stripped “to add to their shame and humiliation”.

These few pages of The Siren during which Nora analyzes and contextualizes this image of Christ make up only a tiny moment of the 400+ page novel. But contained within this single scene is the essence of what ended up being (at this point) an eight book series which has spawned a prequel novel as well as multiple novellas and short stories. The scene concludes with Nora telling Zach that Jesus understands the “purpose” of all the pain and suffering, that better than anyone he understands it’s all for salvation and love. And the idea that suffering (in a myriad of forms, good and bad) and love are inseparable is very much the theme of the entire Original Sinner’s series.

But it is when Nora directs Zach’s attention to the women in the painting that she begins to touch on the aspect of Ciseri’s painting that is most relevant to the “Ecce Homo” scene in The Prince that I want to look at. The two women who appear in Ciseri’s painting are Mary Magdalene and Mary, Jesus’s mother. And in the painting they are the only two not gawking at Jesus the way Pilate invites the crowd to do. Mary cannot even look, she has her back to the scene, and though Mary Magdalene it seems cannot or will not turn away, even her eyes are downcast away from his exposed form.

“Look how Ciseri painted Jesus. See the curve of His back and shoulders. It is a classic feminine posture. His hands are tied behind His back, and His robe is falling over His hips. And all the men are just pointing and staring and gawking. But the women—see them?—they can’t bear it. One’s looking down and she […] can’t even look. She has to hold on to the other woman just to keep from collapsing. […] They know what He’s feeling. The women always know. They know it isn’t just a beating or a murder they’re being forced to witness. It wasn’t even just a crucifixion. It was a sexual assault, Zach. It was a rape.” (122)

It’s a big claim. I remember just having to sit with that analysis for a moment when I first read The Siren because it was so different from every reading of that scene I’d been taught. And I’m sure it would send some scholars screaming into the night, though others might agree with her interpretation. But what is important about Nora’s analysis of the painting isn’t its academic validity or lack thereof. Rather what is important is, again, the way it both illustrates the theme of the entire series and—more specific to my purpose here—foreshadows Søren and Kingsley’s violent (albeit consensual) first time in The Prince.

Behold the Man

Depending on who you ask (or which reviews you read) the scene in which Søren and Kingsely first have sex—in a flashback to their teenage years—is either the first act in a consensual if questionable relationship between two damaged and estranged teenage boys, or it’s a rape. It’s a divisive scene in an already divisive series. But it’s not just the readers shouting rape. The general consensus of the adults in Kingsley’s life is that he has been raped, though they never know it was Søren who was responsible. Even readers who don’t view the scene as a rape are aware of the deliberately ambiguous way in which it was written. Reisz created a scene that was both violent and tender, beautiful and bloody, and leaves it to us to argue over interpretation. She depicts Kingsley’s first submission to Søren as nothing less than a sacrifice of pain and suffering, willingly given.

The imagery and staging in the scene is deliberate, and the similarity to the stages of Christ’s passion unmistakable once you see it—I kicked myself when I realized that I had somehow missed it in prior rereads. I think the only reason that I saw the connection this time was that I was collecting quotes related to Catholicism in Reisz’s series, and had just read the painting scene from The Siren the day before.

The scene in The Prince actually begins with Kingsley running away from Søren. From the moment they met the connection between the two boys felt more like something preordained than just a case of teenage lust (with which Kingsley is very familiar), and Søren frightens Kingsley as much as he attracts him. He is fully aware how much this strange attraction between them has changed his life already. He reflects, moments before the scene in question, that Søren, who he knew then as Stearns, “had ruined him. Ruined everything.” (122). They’re about to be separated for the summer, and instead of celebrating three months back in “civilization,” he’s lamenting being away from Søren/Stearns. He thinks about him constantly. And yet when Søren can no longer resist the connection between them, Kingsley turns and runs into the forest:

“Stearns took a step forward.

Kingsley took a step back.

Stearns stopped.

Kingsley ran.” (123)

I was stuck on this scene for the longest time, trying to figure out why Kingsley runs. He mentions being afraid. Does he have a moment of doubt like Jesus in Gethsemane? On the previous page one of teachers at the school jokes that his rose garden is his Gethsemane, and it is in this Garden, right before Søren/Stearns appears, that Kingsley is praying for strength. But why is he so afraid of something that up until that moment he wanted so much? Or is he afraid because he wants it so much? The dense woods around the school frighten Kingsley but in that moment he runs towards that unknown. Because what’s behind him, what Søren represents, is even more frightening?

It literally took me writing this piece to realize that it’s Kingsley’s fear, not the source of this fear, that matters. His flight through the forest is the portion of the encounter that mimics Jesus’s progression towards Calvary. As Christ must have been afraid while walking towards his death, so Kingsley was afraid running towards his own fears and “death.” So it doesn’t matter whether he was running towards or away from his fears, Kingsley runs knowing that he won’t escape Søren one way or the other. Knowing as Christ did that the sacrifice he is moving towards is inevitable, destined. Though, unlike Christ, Kingsley has no way of knowing what his sacrifice will buy.

As he runs branches whip him, “stinging his skin, his face,” and he forces himself to keep going “despite the pain of the branches beating him, despite the fear that nearly felled him” (124). The scourging. At one point Kingsley drops to his knees to crawl under a thicket and cries out “when the thorns of a bush cut into his forehead” but still he keeps going. The crown of thorns. When Søren catches him at one point, and shoves him against a tree, the bark “bites” into his back, and when Kingsley manages to get loose he rips a little silver cross off of Søren’s neck in the process. He takes it with him when he resumes running, carrying the cross “up the side of the mountain.”

When Kingsley can go no further, Søren strips him naked and forces him down to the ground, and it is Kingsley’s thoughts in that moment which link us linguistically with the painting scene in The Siren:

“This wasn’t how he wanted it…not here on the forest floor, broken and bloodied and terrified. But he would take this pain, this humiliation. For the communion he’d prayed for, he would take it all.” (125)

When Søren first penetrates him, that moment that echoes the piercing of Christ’s hands and feet, Kingsley is laying with “One arm stretched out to the east. The other to the west.” (125) which both indicates that his arms were outstretched in the form of the cross, and which references Psalms 103:12: “As far as the east is from the west, so far has he removed our sins from us.” And all the while Kingsley clings tight to the cross in his hand.

This is where it gets really interesting for me. Because this isn’t just a sex scene that was written this way to be shocking, and the proof is in that verse from Psalms. As Christ died on the cross to forgive the sins of the world, so Kingsley “died” for the forgiveness of Søren’s sins. Of all the characters in this series, Søren’s background is the darkest, and the most horrifying. He can’t forgive himself for what he did (whether it was his fault or not), or for what he is. Not until Kingsley. And it is because of his love for Kingsley, which helps Søren to unlock his heart, that he is ultimately able to become a priest and one of the most compelling, holy figures in the series. Søren is God to Kingsley, to the point where he has such faith in Søren that he is willing to sacrifice himself, despite his fear, in order to earn Søren’s love. But the great beauty of this whole scene is that, to Søren, Kingsley is Christ crucified and Søren himself only a lowest sinner, saved by grace.

The Purpose of Suffering

Okay, so why? Why write this scene this way? Why did Kingsley voluntarily offer himself up to be stripped naked and brutalized on a forest floor, to such an extent that it would take him weeks to heal? And during which period of healing he’d have to suffer being asked by everyone around him who had raped him, as they unknowingly belittled the most transcendent moment of his life? Why subject himself to the pain of any of it? Why did he have to submit himself to all that just for Søren’s sake?

Because in the moment of Kingsley’s death, he understands what Nora refers to in that first scene—what she says Jesus understands: “the purpose of pain and shame and humiliation” (The Siren, 122).

“What is the purpose?” Zach asked, truly wanting to know.

Nora’s eyes returned to the two women in the foreground clinging to each other in sympathy and horror. “For salvation, of course. For love.”

If you’re interested in learning more about Tiffany Reisz’s series and her other works, the best place to start is her website. Along with the Original Sinners series she’s also written a few contemporary romances for Harlequin Blaze, two erotic romances in a second series, and three fantastic novels that lean more towards literary fiction.

I put together a Reading Pathway that can get you started with Reisz’s works, and keep an eye on posts here at Book Riot. For instance, her most recent novel The Rose turned up on our Most Anticipated Books of 2019 post at the start of this year.