A Self-Published Bright Spot at BEA

I was trekking out of Manhattan after a day of hardcore BEA-ing, transferring trains to head back to Brooklyn, when I saw a short man with a wispy mustache and thick, dark, curly hair. I watched him tune his acoustic guitar and slide a capo down its neck. An open, soft-body guitar case rested at his feet, a few coins and a five dollar bill scattered within, next to a small rack of ten-dollar CDs he was hoping to sell.

He closed his eyes and began to strum. Powerfully. Earnestly. Then I heard him. His voice was light and sharp and seemed to hover there in front of him on the subway platform. A man rolling a bicycle past him nodded along in approval. I tossed some money in the guitar case. The busker’s eyes stayed closed. The song didn’t sound like a cover (or at least not of a song I recognized), and the man’s playing was confident and clean. He knew what he was doing.

I wish I’d bought one of the CDs, because the guy was good, but I boarded the train when it arrived moments later and left the busker behind.

…

I was trekking around the Book Expo America floor, gobbling up galleys and generally exhausting myself, when, like a child in a fairy tale, I unwittingly arrived in a strange and unfamiliar place. Next to one of the several stages BEA had set up for various panels and discussions, there was a row of small booths and tables, manned by (often daunted looking) folks peering out from behind stacks of books. Self-help books, business books, history books.

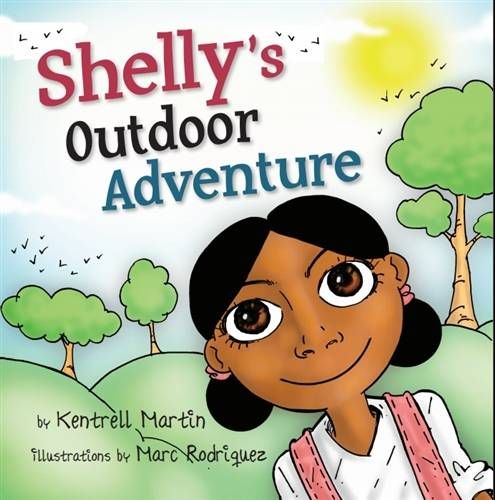

And children’s books. It was a children’s book that caught my eye. A young girl name Shelly stared up from the cover. I introduced myself to the man behind the table, the author of the books, Shelly’s creator, Kentrell Martin. Kentrell was tall and he wore a broad smile. I picked up one of the volumes on the table, Shelly’s Outdoor Adventure, and leafed through it. I pointed to a placard standing up between stacks of Shelly books. On the placard were twenty-six images and twenty-six corresponding letters. The images were hands, and the letters were their meaning in American Sign Language.

I shook Kentrell’s hand and thanked him for the paperback volumes of Shelly’s Outdoor Adventure and Shelly Goes to the Zoo (the only two volumes, for now, that have been published).

Self-published, actually.

When I noticed, I flipped back through the books. Was I expecting them to have lost all their charm? For the signing instructions to suddenly become less clear or typo-filled?

If these sound like the actions of a person with a severe bias against self-published books, I invite you to walk the BEA floor sometime. Witness the self-pubbed authors on the hunt, pressing promotional materials into the hands of anyone foolish enough to make eye contact. Witness the carnival barker-types, yelping to every passerby about the wonders of their unjustly ignored works of genius. Witness the racist novel we found about a coming Islamic theocratic revolution.

Now, maybe the BEA floor isn’t the best place to make judgments about self-published authors and their books. If an author has a booth there, they’ve probably paid a pretty penny for it, and I can understand how, as the Expo wears on, desperation to make the investment worth it might set in. (OK, I feel alright about judging Islamerica, if not the other stuff.)

But self-published authors are just like buskers in that way: they’re easy to ignore, and it takes something special to make me notice one. That’s why, when I saw that Kentrell Martin’s books were self-published, I had to fight feelings of dismissal. He was just like guy on the subway platform, reserved but confident, playing for himself as much as anybody else. I had talked myself out of buying the busker’s CD because, I reasoned, if he were really that great, he wouldn’t be standing at the bottom of the stairs of a subway stop. I didn’t want to talk myself out of a good thing again.

And I’m glad I didn’t. My son starts Kindergarten next year, and on the off chance that he has a deaf or hearing-impaired classmate, maybe the Shelly books can be a tiny bridge between them. In any case, I want to read them to him, and when I get to that point, the name on the inside front cover doesn’t matter anymore.