Picture Books Are the Best Way to Learn Science: A Reading List

I’m not primarily a visual learner, and the picture book and visual rhetoric courses I took during my master’s program were the toughest classes I’ve ever taken in my life — and I took a neuroscience class during my undergrad! (It was disappointingly dissimilar from Oliver Sacks’ books.) But with four niblings and a graduate associateship teaching children’s literature, it’s pretty important that I stay abreast of what’s going on in the picture book world.

One thing I’ve learned as I’ve spent more and more time getting to know contemporary illustrators and authors is that my favorite genre of picture book is nonfiction, and in particular, I like learning about science through picture books more than through any other medium. I’m not talking about the type of book you find in a classroom so you can write reports on an animal, but rather a well-researched and literary codex that can engage me on intellectual and aesthetic levels.

Kids love science. One of the few bright spots of this pandemic is all the extra time I’ve spent with my twin nephews, fiercely intelligent little boys who, and I say this with an entirely serious and not at all precious sincerity, have taught me a ton of interesting things this year. It takes a village to supplement Zoom preschool, and reading science picture books with them has been a treat for all three of us — and the rest of the family, who now all know A TON about bugs, space, chameleons, the island of Madagascar, inches versus centimeters, and more.

Even though I liked science fine enough growing up, what kept me from pursuing it as a college major or a career is the way it’s traditionally taught in the United States: micro first, macro second; it’s as if you’re not allowed to learn the way big stuff works unless you can draw a diagram of a cell and name every part of it. I for one would probably be better at remembering what the rods do and what the cones do if I had first gotten to learn about the science of sight from a more “this little guy talks to this other little guy and sends neural messages to this third guy” perspective before learning the minutiae. If I can understand the general flow of things, I am much more interested in (and will do a better job of grasping) the technical bits. Other people are wired to learn the other way, and I’m a bit jealous of you! But if your mind is narratively oriented like mine, you might be attracted to some of these spectacular works of scientific art that absolutely dazzle, no age limit required. Thankfully, we are in an age where technology has given us pretty amazing quality scans of illustrations, but if you have access to the print books via store or library, you won’t regret opting for that instead.

Note: I’m specifically going for expository nonfiction here, so you won’t see biographies of famous (or under-recognized) scientists here, nor will you see fiction about kids doing science. That is an area where picture books are really excelling, and there is really great diversity in who is covered and highlighted. But for now, I’m focusing on scienCE, not scienTISTS.

Island: A Story of the Galapagos by Jason Chin

Absolutely every single thing Jason Chin does is a masterpiece, but if you made me pick just one, I’d probably go with this book about the Galapagos islands, their relationship with Charles Darwin being maybe the least interesting thing about them (though plenty interesting). In this book, the Galapagos is a living, breathing character, but not in a cutesy way — actually, that’s a pretty good brand slogan for Chin: presents his subjects as living and breathing characters, but never in a cutesy way. We learn about it from the dawn of time, literally, and see how it developed as a land mass and how all the animals and plants on it work together to thrive. Chin’s books are pretty much all in portrait orientation, which makes you feel completely a part of the action. All you have to do is slide open a door and you’d be right there.

If Sharks Disappeared by Lily Williams

Shark movies are my absolute jam, though I’ve somehow never seen Jaws (? I know). Visceral, emotional performances or preposterous premises with eight-figure budgets are all great, but I’m also completely into the awful ones, some of which are so bad that they make Sharknado look Oscar-worthy. Until reading this book, though, I had never really thought about what that trope does to the real fish out there who are just trying to live their lives. We so gleefully indulge in the thrill of these creature features, but sometimes that manifests in animal violence, overfishing, destruction of habitats, and more. While “cute” is not my favorite point of view, the cutesy (but not saccharine) illustrations actually work nicely here, because they help soften the unwarranted fear kids may have over the numerous shark species that really aren’t much of a danger to us (though there are certainly some that are). Also, the ur-child who goes through this learning journey is brown, for no other reason than that some children are brown, and that’s always a bonus, especially in STEM, where we still see far more white boys than any other demographic represented.

Honeybee by Candace Fleming and Eric Rohmann

Honestly it almost feels not worth mentioning here, because I know this is getting all the award buzz and I don’t like to be a conformist, but this eye-catching project by a husband-and-wife powerhouse team who are also known for their work created independently (for example, The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion, and the Fall of Imperial Russia by Fleming and My Friend Rabbit by Rohmann) is too amazing not to share. Like If Sharks Disappeared, the subject of this book is a much-maligned creature that is now in serious danger — the bee. The last time I learned so much about the insects who literally keep the world from dying was an episode of The Magic School Bus, and this one is decidedly more realistic than watching Arnold dance. Did you know that bees don’t just have roles in the hive (as I thought), but they actually do all of them? They move up the ranks just like workers in a utopian capitalist meritocracy. Our protagonist Apis (which just means “bee,” but don’t tell my nephew that — we had to name the other bees around her so she would stand out) begins life and spends many days — and many pages — working to keep the hive going before she ever gets to fly. Fleming’s text is informative but lyrical, and Rohmann’s art is all but photorealistic, with the pages saturated with rich color and full bleed so you feel a little like you did hop on Ms. Frizzle’s bus, miniaturize, and take a tour of a real hive.

The Stuff of Stars by Marion Dane Bauer and Ekua Holmes

My review immediately after I read this book during one of my graduate classes: “It is a poem! In a picture book! With marbled illustrations! ABOUT THE BIG BANG!!!!” I still feel just as !!! about it two years later. You can practically smell the paint there’s so much of it on each page, and I love that it’s a medium that so many children love to do themselves — thick paint — combined with a type of literature we respond to very early on, before we learn to fear it in English class: poetry. The Big Bang is a topic that is pretty difficult to grasp, but packaging it this way is a good way to start. Who knew you could pair poetry with science?

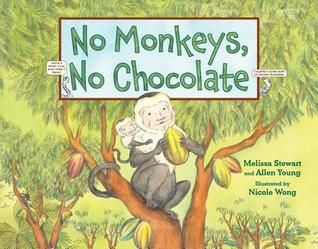

No Monkeys, No Chocolate by Melissa Stewart, Allen Young, and Nicole Wong

If you can look past some of the dated puns and jokes in this book (remember iPods?), you’ll learn a whole lot about the life cycle of a cocoa tree, microhabitats, and the somewhat vicious creatures that must live and die in order to give us what we love — chocolate! Every page gives you info on another creature or event essential to the growth of the cocoa tree, and each page also hearkens back to the creature or event previous, because, y’know, the circle of life and all. I read it for the science; kids will read it for the science and probably love the extra gross bits, like how maggots eat ants’ brains from the inside in order to keep the ants from killing the cocoa tree, and just…bear with the book, because it takes awhile to get to the monkeys, but there are tons of other creatures doing their part along the way.

Swirl by Swirl: Spirals in Nature by Joyce Sidman and Beth Krommes

When people talk about math in nature, I know the proper response if you want to sound like you know what you’re talking about is “Fibonacci!” and I know what the Fibonacci sequence is (if it’s been a minute since math class, the sequence begins 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 — each number comes from adding the two numbers preceding it), but I didn’t really know how it worked in nature. Now I do, thanks to the glossary in the back of this book, which in the book proper is a spare, understated poem and amazing scratchboard illustrations. Like any good nature book, the illustrations are labeled (ram’s horn, nautilus, spider monkey, and more), but they’re not intrusive, so you can enjoy the art, the poem, and the science in whatever combination you wish.

The Mess That We Made by Michelle Lord and Julia Blattman

Come for the damning diatribe on plastic waste and ocean health, stay for the take on “This Is The House That Jack Built!” It’s not that I didn’t know that plastic is bad for the planet, but this book goes a long way to explain the how behind it, all through a repetitive, rhythmic poem that I honestly didn’t even realize was “The House That Jack Built” for a few stanzas. It’s a pretty genius idea, because it makes it clear that plastic pollution is not an isolated incident but almost an ecosystem of its own — turtles see plastic bags and think they’re jellyfish; seals eat fish that have been gobbling up microplastics; seals get caught by ships that stir up pollution from leaking landfills…and lest you think it’s all bad news, the poem shifts and we get another cyclical look at the ways we can very easily fix this problem through small and big actions. The backmatter explains further, but unlike a lot of science picture books that save all the explanation for huge masses of text in the back, this one manages to explain and be literary at once. The illustrations are also beautiful, brilliantly blending the plastic into the ocean so you can recognize it as plastic by shape but also see how it can easily confuse sea animals who, y’know, have no frame of reference for things like “Target run.”

My Tata’s Remedies/Los Remedios de mi Tata by Roni Capin Rivera-Ashford and Antonio Castro L.

This one is technically fiction, but the fiction is really just a vehicle to contextualize the science, so it fits this task in my book. I love that it will feel very familiar to kids who have healers in their families or communities, and for children or adults who don’t, it’s a great reminder that pharmaceuticals come from nature first, not a factory. A young boy spends the day with his grandfather and watches as members of the community come to him with familiar maladies like headaches, bee stings, diaper rash, and burns. As Tata’s assistant, little Aaron is responsible for running to the garden or to his grandfather’s readymade stash of tinctures, dried herbs, and more. You might think the moral of the story is “who needs Neosporin when they have a medicine man,” but that’s not quite it. Read this book the next time you have a health concern that doesn’t require a hospital! If you read the ingredients list on the OTC cream, gel, or pill you’re taking, chances are its active ingredient is something Tata gets out of his garden, like arnica, aloe, or elderberry. The backmatter, in both English and Spanish just like the story, serves as a nature guide and explains in even more detail how the plants in your backyard are the basis for a lot of the jars and tubes you have in your medicine cabinet. I’m not saying that I or this book make a good substitute for a medical professional, but I am saying that for the aches and pains you were treating on your own anyway, this book is a useful field guide.