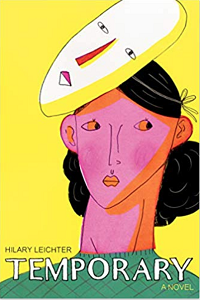

Reflecting on the Nature of Work With Hilary Leichter’s TEMPORARY

I began reading Hilary Leichter’s Temporary at the beginning of quarantine. I’d managed to lose two jobs in the second week of my state’s stay-at-home order, so I had plenty of time on my hands to read. But, like many people, I had a hard time concentrating. The news was distracting and disturbing and hard to ignore. Additionally, I was unemployed and didn’t know how I’d ever find a job when everything was shut down. Reading felt like an indulgence when I should have been busy looking for a job or something. Instead I paced and chewed on my fingernails, allowing my mind to race through all the terrible pitfalls of being jobless during a recession and a pandemic.

In an alternative world, defined and bound by gig work, finding steady employment is life’s only objective. To achieve “the steadiness” of permanent employment, the narrator of Leichter’s story must perform well in every provisional position she fills.

“I consider my deepest wish. There are days I think I’ve achieved it, and then it’s gone, like a sneeze that gets swallowed. I’ve heard that at the first sign of permanence, the heart rate can increase, and blood can rise in the cheeks. I’ve read the brochures, the pamphlets. Some temporaries swear it’s that shiver, that elevated pulse, that prickly sweat, the biology of how you know it’s happening to you. I worry I’ll miss it, simply overlook the symptoms of my own permanence arriving. The steadiness, they call it.”

Throughout the story, the narrator has many jobs that are unlike anything that could be found in our own employment offices. She cleans the windows of a skyscraper, directs traffic, shines shoes in a rich woman’s closet, and fills in for the Chairman of the Board at a “very major corporation” called Major Corp. At Major Corp “I sign documents I don’t understand, sit in on conference calls, stack memos and stamp the dates, fiduciary and filibuster and finance and finesse and fill the office walls with art selected from a list of hip emerging painters, and finish each assignment before anything can be explained in full.”

Eventually she is assigned to a pirate ship, assists an assassin, plays a barnacle attached to a rock in the middle of the ocean, haunts a house, and fills in for an absent mother.

As her jobs become more and more absurd, the narrator slowly reflects on the futility of her cyclical life. What is life outside of employment? She has 18 boyfriends to fulfill 18 different needs, but not one of these men seem to give her any real and lasting pleasure. While she is filling in for a mother, her temporary son asks her to “get sad, and stare out the window.” It isn’t until she has exhausted all options, when her life becomes most desperate and employment starts to dry up, that she begins to question her life and existence in a world of hustle and bustle.

“Life is a stranger in a crowd whose intentions are unclear and, come to think of it, so is death.”

When caught up in a long work day that is only part of a long work week, it can be hard to stop and reflect upon the fruitlessness of the work many of us do everyday. We are all caught preoccupied and are unable to examine our own place on the conveyor belt of late capitalism. We are distracted and conditioned, like the narrator in Temporary to keep chugging along without questioning the conditions or destination of our work life.

In Studs Terkel’s Working, an oral history on the nature of work compiled in the 1970s, Nora Watson, whose section is found under the chapter “In Search of a Calling,” is a writer and editor who begins her interview like this: “Jobs are not big enough for people. It’s not just the assembly line worker whose job is too small for his spirit, you know? A job like mine, if you really do put your spirit into it, you would sabotage immediately. You don’t dare. So you absent your spirit from it.”

In the United States, work means health insurance, a savings account, retirement. Without work, life feels desperate. There are few safeguards for the unemployed. Destitution begins breathing down our neck, and quickly, without taking a breath, the wretched attempts of finding a new job must begin.

“When a temp dies before the steadiness, it’s said she’s doomed to perform administrative work for the gods in perpetuity.”

Now, with so many of us unemployed, might be a good time—if we are able—to start questioning our country’s employment system. For instance, the federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour. Wage growth has been stagnant for 40 years. Where I live, a living wage is $10.86 per hour. And employers of tipped employees only have to pay those workers $2.13 per hour.

Again, Nora Watson:

“You throw yourself into things because you feel that important question—self- discipline, goals, a meaning of your life—are carried out in your work. You invest a job with a lot of values that the society doesn’t allow you to put into a job. You find yourself like a pacemaker that’s gone crazy or something. You want it to be a million things that it’s not and you want to give it a million parts of yourself that nobody else wants there. So you end up wrecking the curve or else settling down and conforming.”