7 Reading Recommendations from Prof. Joe Farag’s Palestinian Literature Syllabus

Over at ArabLit, we’ve started a series on teaching with Arabic literature in translation. The first Q&A was with the brilliant Emily Drumsta, who teaches at Brown, about teaching “Women’s Writing in the Arab World.” The second, with University of Minnesota Prof. Joseph Farag, is about teaching “Palestinian Literature and Film.”

For those who aren’t instructors, I’ve pulled out 10 recommended reads from our discussion.

1) Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun, All That’s Left to You, and “Land of Sad Oranges.”

Translations by Hilary Kilpatrick, May Jayyusi and Jeremy Reed, and Nejmeh Habib.

Farag says:

I freely confess to engaging in shameless sentimentalism in my opening with Kanafani’s short story, “The Land of Sad Oranges.” The fact is, that was the first piece of Palestinian literature I ever encountered, and I found it so deeply moving, poignant, and beautiful, despite its bleak subject-matter, that I’ve resolved to make it the first story my students encounter as well.

2) Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, The Ship.

Translated by Adnan Haydar & Roger Allen.

Farag:

For students…the setting of the novel, aboard a ship laboriously making its way around the Mediterranean, briefly docking at ports here and there, but remaining ever itinerant, productively evokes the dilemma of exile and Palestinian displacement and itinerancy.

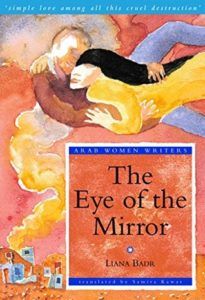

3) Liana Badr, The Eye of the Mirror.

Farag talks about how the novel illustrates:

…the ways in which the power dynamics of gender are dynamic, fluid, and ever-shifting, especially in conditions of conflict. The patriarch of the family at the outset of the novel is reduced to a sorry shadow of himself by the end, while the meek and timid women in his family, and in the camp as a whole, emerge as strong – though it would be a stretch to say “empowered” given their situation[.]

4) Anton Shammas, Arabesques.

Translated by Vivian Eden.

Arabesques — a book about identity, memory, and history — was chosen as one of the best books of 1988 by the editors of the New York Times Book Review.

5) Emile Habibi, The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist. Translated by Trevor LeGassick and Salma Jayyusi.

Farag, about Habibi’s humor:

I’m not sure that students always find Pessoptimist as laugh-out-loud funny as I do, but they certainly pick up on the humor in it and, as you say, by that point in the syllabus, having witnessed so much tragedy, it’s badly needed.

6) Sayed Kashua, Dancing Arabs.

6) Sayed Kashua, Dancing Arabs.

Translated by Miriam Shlesinger.

And the also funny Dancing Arabs:

As for Dancing Arabs, I chose it for its portrayal of the fraught dynamics of the subjectivity of Palestinian citizens of Israel, which I think it does more explicitly than Let It Be Morning. I admit I have yet to read Second Person Singular (so many novels, so little time!) so I can’t speak to that one. The deep shame and self-loathing at being Palestinian demonstrated by the unnamed narrator of Dancing Arabs – indeed, the very fact that he remains unnamed, i.e. identity-less – throughout the novel speaks eloquently to the stigmatization of Palestinian identity in Israeli society, where Palestinians are euphemistically referred to as “Arab Citizens of Israel,” thereby erasing their Palestinian-ness.

7) Ibrahim Nasrallah, Prairies of Fever.

Translated by May Jayyusi and Jeremy Reed.

Farag:

[T]he fact that so many decades after the publication of Kanafani’s Men in the Sun, Nasrallah should strike such an existentially uncertain note in Prairies goes to the heart of the continued precariousness of the Palestinian subject given Palestinian statelessness and exiled dispersal.

See the whole discussion on teaching with Palestinian literature at ArabLit.

6) Sayed Kashua,

6) Sayed Kashua,