Meet the People Who “Drank the Kool-Aid” (And Why We Should Stop Saying That)

With a toddler around, it takes me longer these days to finish books than it used to. But I blew through Julia Scheeres’s 2011 nonfiction book, A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Jonestown in two days. It was that harrowing. That gripping. That empathetic toward the people who lost their lives to the Peoples Temple in November of 1978. And it convinced me to erase the phrase “Don’t Drink the Kool-Aid” and any of its iterations from my vocabulary.

Even though I was born in the ’90s, I’d heard plenty of people talk about Jonestown before I read the book. Something about a charismatic leader, a huge cult, and poisoned Kool-Aid.

But in her book, Julia Scheeres focuses not on the sensationalism of the act—widely called the largest act of “mass suicide” or, at best, “murder-suicide” in modern history—but on the people that Jim Jones groomed for years before forcing them to drink poisoned Flavor-Aid.

There’s Hyacinth Thrash, an Alabama-born descendant of enslaved people who found Jones’s early message of social inclusivity encouraging. She and her sister Zipporah followed Jones, not without careful consideration and even hesitation, to northern California and then Guyana.

There Zipporah died on November 18 with over 900 others. Hyacinth, an elderly woman by then, survived. She published a book about her experience, The Onliest One Alive: Surviving Jonestown, Guyana.

The sisters had believed in Jones’s progressive message for over 20 years.

There’s Stanley Clayton, a young Black teenager whose broken home life drove him to search for community. He found it in the Peoples Temple. He hoped Jones could cure him of his various addictions, but Jones only brought him to Guyana and put him to work.

Stanley fell in love with another teenager named Janice, and in the end he held her in his arms as Jones’s poison shut down her body. He escaped by running into the jungle and hiding until the dying ended.

At the time of the book’s writing, Stanley said that he missed his Peoples Temple family. His words make me ache: “‘There were a lot of people in the church who believed in me and supported me,’ he says. ‘I don’t have that no more'” (248).

There’s Edith Roller, a progressive, educated woman who found that the Peoples Temple’s ideals aligned with her own. With much pressure from Jones, she reluctantly gave up a comfortable life on her own to live communally.

And she hated it.

Like every other Jonestown resident, she got tricked into thinking Jonestown was a lush utopia. (Jones spruced up select cabins and carefully filmed scenes of harmony, cleanliness, and plenty to convince people that Jonestown, Guyana was THE place to go).

Upon arriving, Edith learned the hard and terrible truth. Still, she tried to make her corner of her communal cabin a cozy place to sleep. She kept steady daily notes on the goings-on of Jonestown until she died that day with everyone else.

And don’t even get me started on the babies. So many babies and young children were forcefully fed the Flavor Aid (that’s what it was, not Kool-Aid) that day. It’s hard to even think about.

Were their parents evil for doing this? No. They were depressed, hungry, exhausted, and manipulated into doing something terrible. And I hope that in their situation, I would have attempted escape, as some mothers did.

But Jim Jones constructed a community so large, so all-encompassing, that it was its members’ entire lives. I grew up in a church community that felt the same way—my days ran by its clock, and the members of its community were my family.

The only difference is that I did not have an unhinged leader slowly and deliberately pushing me, my whole family, and our entire friend circle toward an unthinkable and agonizing death.

And when I say push, I mean hard. Jones manipulated, fear-mongered, cajoled, punished. He publicly whipped adults and children. He assigned teenagers to brutal, guard-flanked work units. He held “suicide votes” night after night in the months before the murders, and if you didn’t raise your hand, he called you out. He would not let you go to bed until you agreed to it.

He intercepted all forms of media and set up fake attack scenarios to make it seem that outside forces were creeping in, ready to obliterate every last person.

Without his bullying and his punishments, there would’ve been no mass death.

A lot of people call the Peoples Temple a cult. But Julia Scheeres doesn’t: “The word cult only discourages intellectual curiosity and empathy,” she says. “As one survivor told me, nobody joins a cult” (xii).

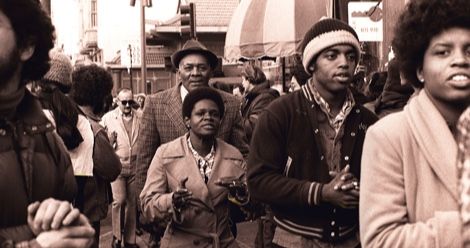

The Jonestown tragedy wasn’t a bunch of cult members “Drinking the Kool-Aid.” It was hundreds of people, many of them Black, who’d found a community with a message they could support.

It was hundreds of people who believed they were headed in a direction of peace, equity, and inclusivity and instead were carefully and subtly led down another path altogether.

Get to know their faces. These are victims. And they’re people whose memory I won’t ever disrespect again by offhandedly using a saying like “don’t drink the Kool-Aid.”