The Essential, Authoritative, and Indispensable Collection of Literary References in Calvin and Hobbes

While some beacons of childhood nostalgia are better left as memories, I suspected Calvin & Hobbes might warrant a revisit. Indeed, what I loved about the comic as a kid — both the gruesome snowmen and the pure love of a stuffed animal — has remained delightful. But my eyes, now bespectacled and beginning to crease with wrinkles, can detect more than they could back when they were in mint condition. Namely, the comic’s depth of references — artistic, political, philosophical, and, yes, literary.

Perhaps the best works created for children are the ones rife with layers discoverable later in life. That quality encourages intergenerational sharing. It makes the works enduring. Maybe, like me, you’ve read hundreds (or thousands!) of books and generally soaked up a lot of culture in the time since you last visited our spiky-haired boy and his tiger friend. If so, here are some literary references you can pick up on a Calvin and Hobbes reread.

The Titular Characters

I think for most people around my age and younger, knowledge of Hobbes the tiger came before knowledge of Hobbes the political philosopher. Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson named Hobbes as a wink to his background in political science. He’d chosen the major to augment his planned career in editorial cartooning. I, for one, am grateful he opted for the funny pages over the op-eds. Watterson characterized Thomas Hobbes as having “a dim view of human nature.” How much tiger Hobbes reflects philosopher Thomas Hobbes is debatable. While the tiger Hobbes laments human ills like environmental destruction, he also clearly loves his human companion.

Calvin, meanwhile, shares a name with theologian John Calvin, the namesake of a major branch of Protestantism. John Calvin’s claim to fame is the notion of predestination, meaning that God has already chosen an unchangeable elect, and the remaining reprobates face eternal damnation. Comic Calvin does not have a particularly consistent philosophy; it’s part of his charm. But he does invoke his namesake in one strip when he says “All events are preordained and unalterable. Whatever will be will be. That way, if anything bad happens, it’s not my fault.”

Influence and Homage

Bill Watterson himself described three of his biggest influences in comics, and references to their work permeate Calvin and Hobbes. The first of these is Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. Both Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes revolve around a boy and his relationship to an animal friend. Charlie Brown has Snoopy; Calvin has Hobbes. Stylistically, Watterson, like Schulz, drew, lettered, and inked every strip he created.

Both Charlie Brown and Calvin have misfit qualities. Neither excel at sports, though Calvin makes up for this by inventing his own, Calvinball. Charlie Brown and Calvin both have antagonistic relationships with girls in their class. And ultimately, both comic strips center the world of children over the world of adults. Where they differ is in mood. Peanuts captures the melancholy of childhood, while Calvin & Hobbes depicts more of the wonder.

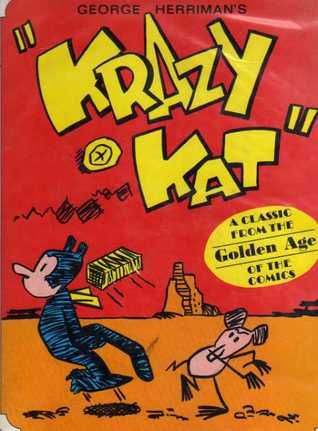

If you’ve never read the comic strip Krazy Kat, you’re missing out on some genuine weirdness that also influenced Bill Watterson. Krazy Kat, which first ran in 1913, showed how a comic could be deeply idiosyncratic and still appear in the papers. George Herriman, who created the strip, also elevated the artwork of the medium. Whenever a Calvin and Hobbes comic depicts a Martian landscape for a Spaceman Spiff adventure, Krazy Kat was there first. The comic’s setting of Coconino County provided the stark desert landscape Bill Watterson loved to replicate in his own work. Watterson even gave it a specific reference in one strip where Calvin’s parents admire a painting in a museum. That painting is actually a reproduced Krazy Kat landscape.

For a long time, I never knew what the deal was with the poetry in Calvin and Hobbes. Calvin is often made to recite poetry, frequently penned by Hobbes and more frequently lauding tigers’ merits. Those occurrences in Calvin and Hobbes are an homage to Walt Kelly’s Pogo, which often featured Kelly’s own poetry. Pogo was a strip about talking animals in Okefenokee Swamp. And like Calvin and Hobbes, the characters are richly developed and multifaceted.

Genre References

Aside from those three major influences, Calvin’s alter egos pay homage to a love of comic books and pulp fiction. His Spaceman Spiff persona is a send-up of early science fiction pulp magazines like Amazing Stories, which published stories of Buck Rogers. Tracer Bullet is Calvin’s noir alter ego, reminiscent Dick Tracy. When we get to see Calvin’s nemesis Susie’s imaginary life with her stuffie, Mr. Bun, it can take the form of dramatic comics like Mary Worth and Dr Kildare. That love of pulp literature even sneaks through when Calvin’s mother refers to her husband as Conan the Barbarian.

Calvin is far more interested in comic books than other literature. When he describes his superhero character Stupendous Man as being “mild-mannered” and a “millionaire playboy” out of costume, he’s referencing both Superman and Batman in his paradoxical description.

Specific Literary References in Calvin and Hobbes

Copious literary references in Calvin and Hobbes come in the form of one-off occurrences. Calvin’s ideas spring from the mouth of a child, but many have roots in other writers. When Calvin says “the ends justify the means,” only to take umbrage at Hobbes shoving him into a mud puddle to get Calvin out of his path, he’s paraphrasing Machiavelli’s The Prince. His desire to live alone in the woods away from the society is certainly referencing Thoreau’s Walden, right down to the detail where Calvin says he’ll need his mom to come and cook for him.

The adventures Calvin and Hobbes embark on often resemble adventurous stories from throughout history. Calvin finds a magic carpet, immortalized in the Thousand and One Nights. A cardboard box becomes a time machine, an object coined by H.G. Wells. When Calvin floats into the air with a single balloon, all I see is “In Which We Are Introduced to Winnie the Pooh and Some Bees and the Stories Begin,” the very first story in the Winnie the Pooh collection.

Calvin’s fanciful imagination also calls on some classics. When Calvin awakes in the morning as a human-sized slug, Kafka’s Metamorphosis leaps to mind. Hobbes even accuses Calvin of getting “Kafka dreams.” And sometimes it’s hard not to reference the Bible if you’re writing in English. Biblical phrases are plentiful in our lexicon. But Calvin goes for a full Gothic font and demands sacrifices like Old Testament God when his imagination narrates his tinker toy play. Another religious undertone comes in the form of Mrs. Wormwood. Calvin’s teacher’s name is that of the apprentice devil in C.S. Lewis’s novel The Screwtape Letters.

What exactly does Calvin read?

Apart from Calvin’s bedtime favorite Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie and nonfiction books about dinosaurs and wasps, he doesn’t express much interest in books that aren’t comics. Nevertheless, he spouts some pretty erudite references. These musings often come in the strips that portray Calvin and Hobbes on a trek through the woods. One such trek depicted Calvin’s escape after driving his mother’s car into a ditch, when he quotes the title of Thomas Wolfe’s novel You Can’t Go Home Again.

And when Calvin described a walk in the winter as reminiscent of Doctor Zhivago, had he seen the film or read the book? Calvin tried to bring his snowmen to life through a lightning strike, an allusion to cinematic adaptations of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which suggests to me he picks a lot up from the movies. Still, how Calvin was able to describe the theory of general relativity Einstein presented in his article “On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light” when delaying telling his mother that he’d spilled a pitcher of lemonade is anyone’s guess.

We know Calvin reads Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie, but that’s an imaginary book. Nevertheless, one enterprising author did take advantage of copyright loopholes around titles to write the book themselves. I don’t believe anyone has yet published the sequel, Commander Coriander Salamander and ‘er Singlehander Bellylander.

Hobbes, often depicted reading, can also drop a reference or two. Much of the poetry in Calvin and Hobbes takes the form of odes Hobbes writes to himself, but he will paraphrase other poets, including Alfred Lord Tennyson’s famous line from “Locksley Hall,” “In the Spring a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love.”

The Rich Text of Calvin and Hobbes

What do all these references add up to? They underscore the adventurous nature of Calvin. He goes where lots of other heroic characters have gone before, but always with a humorous and imaginative twist. Likewise, the contemplative moments highlight the richness of a life steeped in literature, philosophy, and art. These references add wisdom and heft to Calvin’s childlike wonder. Ultimately one might say there’s nothing like Calvin and Hobbes, but there are some comics that evoke the same feelings.

In the end, I believe I’ve only scratched the surface of the literary references in Calvin and Hobbes. While reading, I’d often find myself wondering, exactly which philosopher is this again? Or, doesn’t that sound a little bit like something Pierre says in War and Peace? But I couldn’t always put a finger on what felt like an allusion. You, dear reader, with your own knowledge and cultural touch points, are sure to find plenty more.

I called this essay “Essential, Authoritative and Indispensable” for the same reason Bill Watterson used those adjectives to describe his Calvin and Hobbes collections. This article is anything but essential, authoritative or indispensable! So as Calvin says in the final strip, “It’s a magical world, Hobbes ol’ buddy, let’s go exploring!”