Texas Ranks Among Lowest on Library Use, Highest in Book Bans: Library Use & Spending By State

What states invest the most money per capita into their public libraries and how is that reflected in the number of visits per person at those libraries? Thanks to a new report pulled together by Scholaroo, a team who helps students find and acquire scholarships, we can get a sense of where and how people use one of their finest public goods.

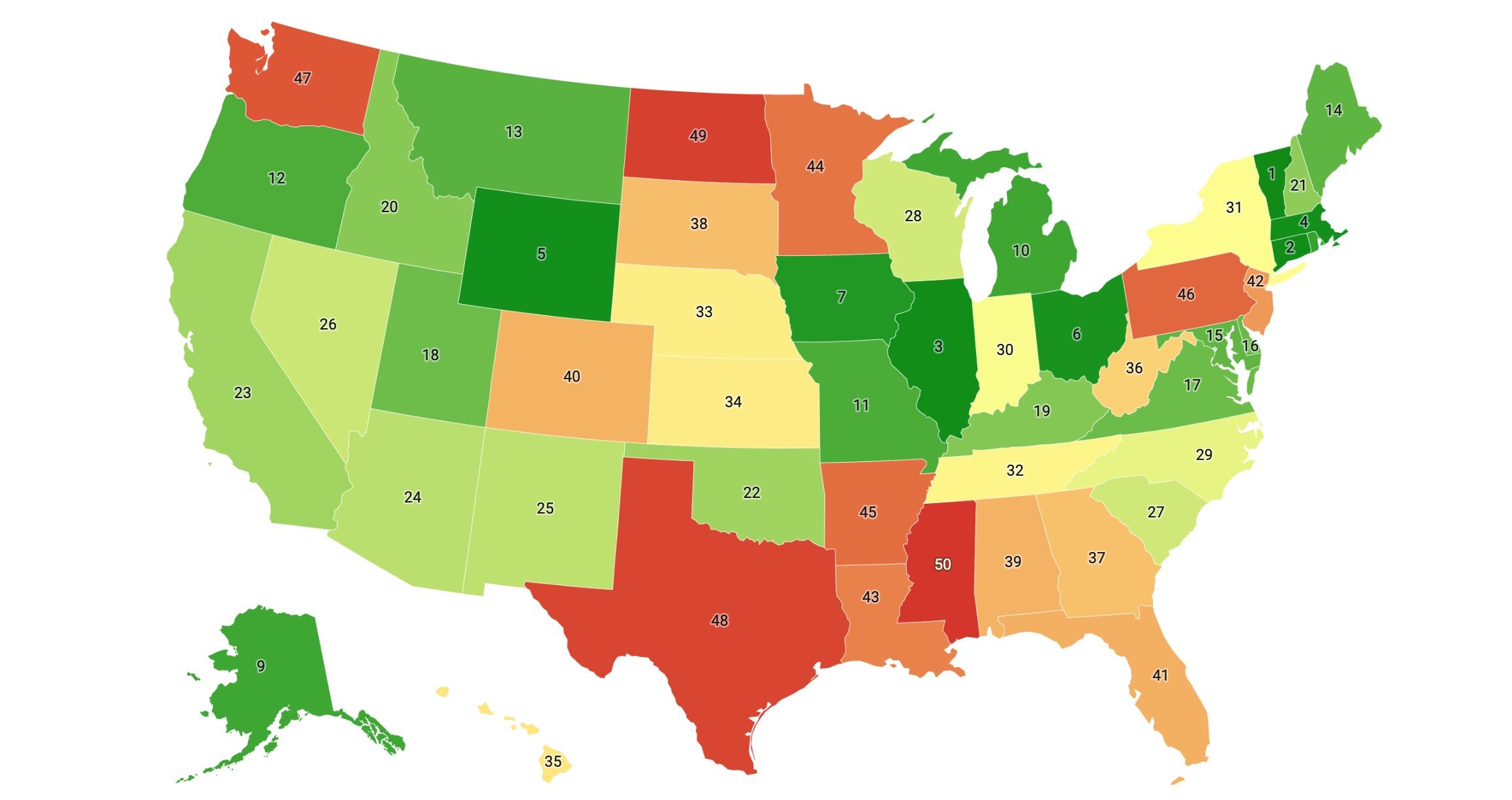

Utilizing data from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Scholaroo first looked at the number of visits to public libraries per capita.

The top five states for library use are Vermont, at 4.015 visits per capita per year; Connecticut, at 3.984 visits per capita per year; Illinois, at 3.958 visits per capita per year; Massachusetts, at 3.907 visits per capita per year; and Wyoming, at 3.901 visits per capita per year.

The lowest five states for library use per capita include Mississippi, 1.174 visits per capita; North Dakota, 1.201 visits per capita; Texas, 1.214 visits per capita; Washington, 1.273 visits per capita; and Pennsylvania, 1.332 visits per capita.

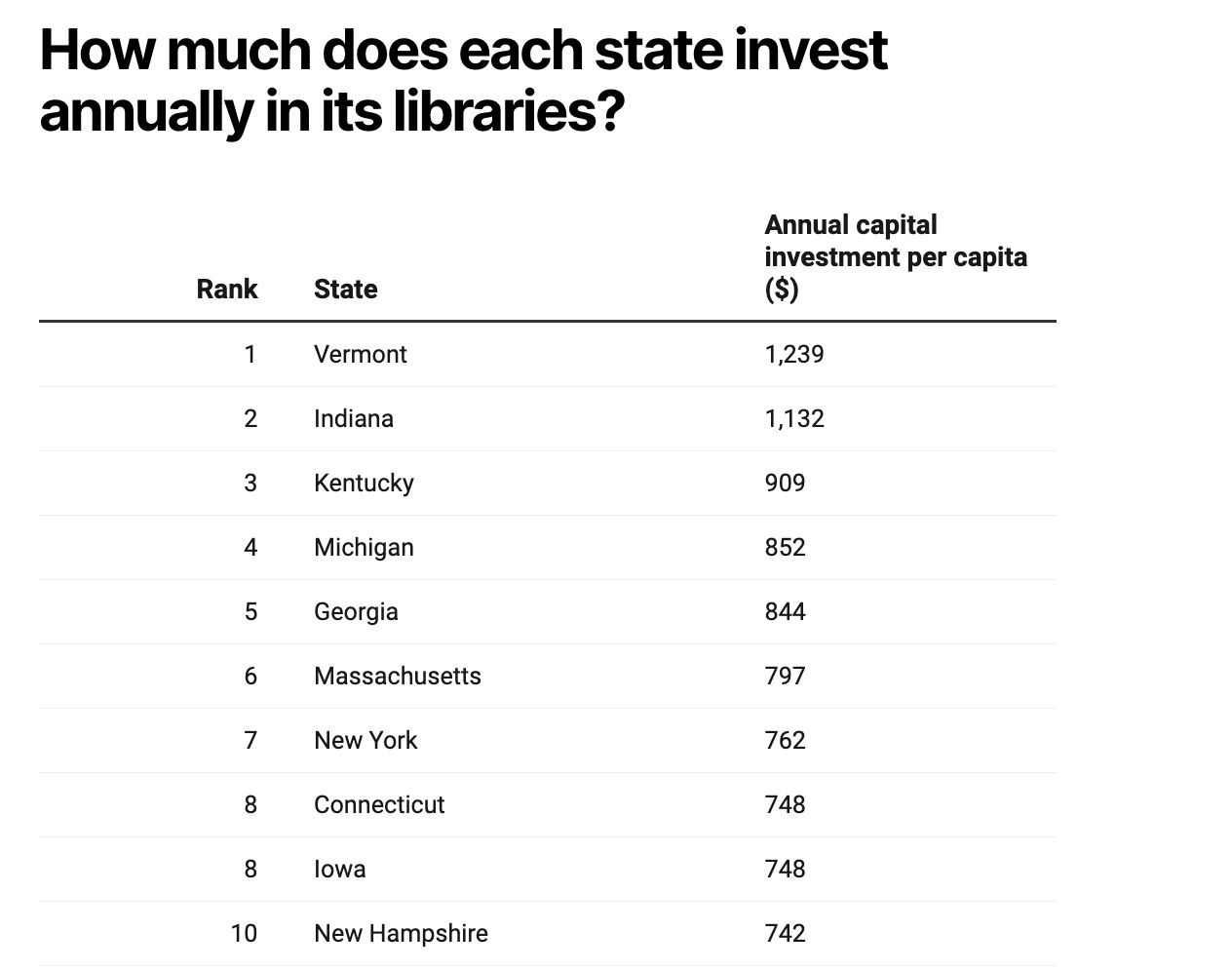

It would be easy to assume that states which invest more money into their public libraries see that in their use. But that’s not necessarily true.

Vermont tops the charts here, as it does in per capita use. But Indiana follows not far behind. Despite funding their libraries well, they rank at 30 for use per capita, at 1.968. Kentucky ranks third for investment but 19 for use, while Michigan ranks fourth for investment and tenth for use. Rounding out the top five is Georgia, fifth in investment and thirty-seventh in use.

At the bottom of the list for library investment are Mississippi–which is also last in use; Wyoming, which is surprising given that it ranks in the top five for use; Nevada, twenty-sixth in use; Alaska, ninth in use; and Alabama, thirty-ninth in use.

Every state uses a different mechanism for funding their public libraries. In most, though, it is related to taxes and library usage, so it’s not entirely surprising to see that places with better access to funds for libraries tend to see that play out in how those libraries are utilized. If you’re in a rural, lower-income state, you simply do not have the money to fund these institutions in the same way that wealthier, more urban states can. The cycle builds upon itself, and it leaves those with the most need having access to the least resources.

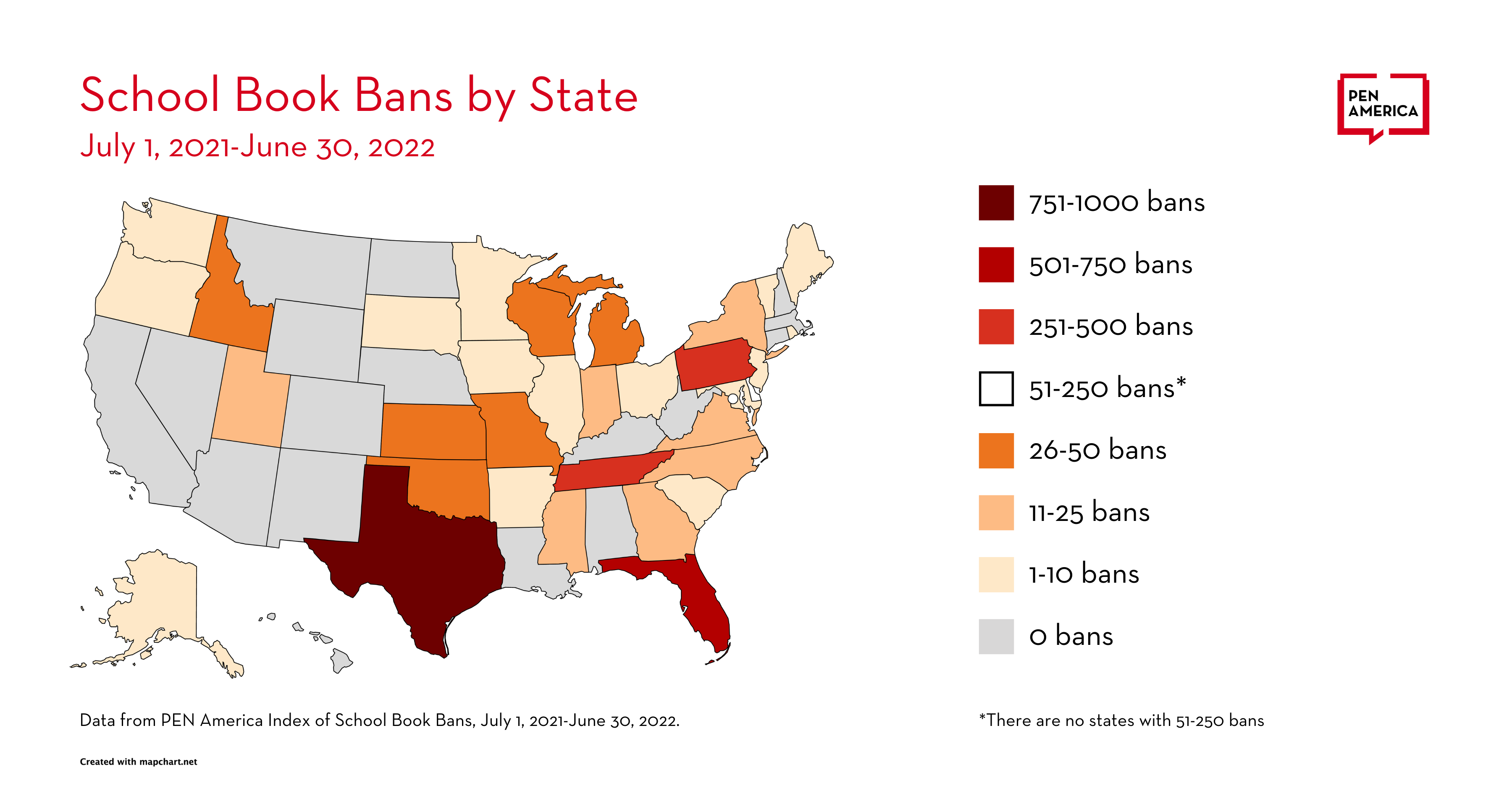

This data is interesting in an of itself, but let’s add another layer to it. Let’s now overlay the information we have about book bans.

PEN America has been keeping information about book bans, including where those bans are happening. While their most recent data report from September looks at school libraries, as opposed to public libraries, it’s still a worthwhile comparison.

Texas tops the list in school library book bans, while also at the bottom of the list of public library use per capita. Likewise, Pennsylvania ranks at the top with school library book bans while near the bottom in public library use. Florida, too.

What’s interesting, though, is where the numbers do not align. Look at Missouri: it has one of the higher concentrations of school book bans while also ranking just outside the top ten for use per capita. It also ranked twelfth in state funding. Could this information be partially why the legislature there decided one way to get what they want in terms of book bans is to cut public library funding all together? If the institutions that the population uses are defunded, then they can’t use them, and thus, those institutions begin to wither, lose their vitality, and can be all together shuttered.

One of the common lines from both those who are eager to ban books and those who believe it the solution to those school book bans is that those books are accessible at the public library. But are they? And if so, what happens if those institutions are not funded well? Or they’re inaccessible?

Because the reality is, all of these things come into play when considering why some states have more ample use of their public libraries than others.

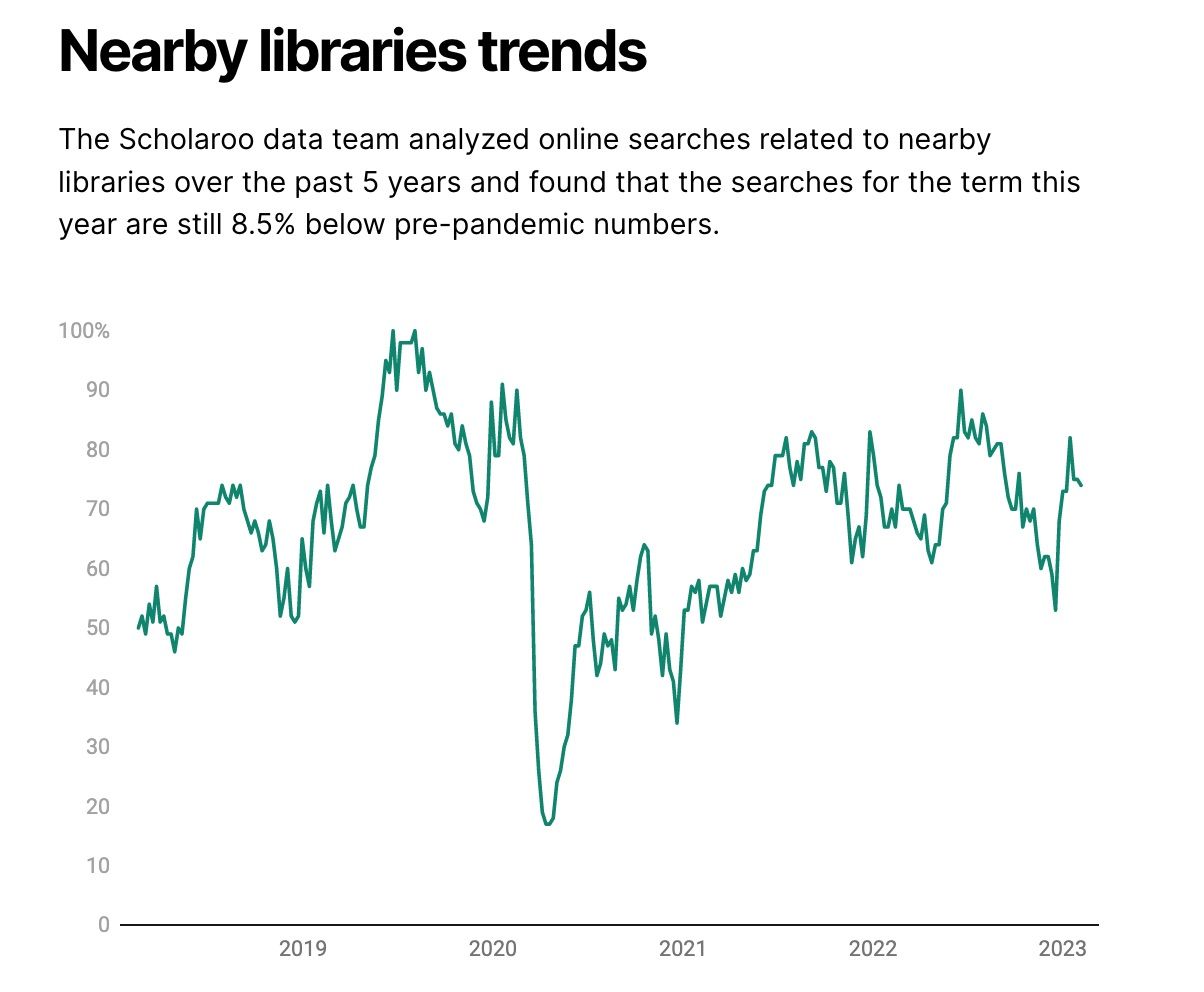

We already know book bans are driving kids away from libraries and from reading. But Scholaroo adds another interesting element to consider: how much are people even searching for their nearby library?

Even the activity of looking for information about nearby libraries has remained lower since the beginning of the pandemic.

Not all of this can or should be tied to book bans. But it would be wrong to not bring it up at all. Book bans are guiding policy across a dozen or more US states, particularly in those where usage already ranks lower.

It’s not hard to imagine a world where, in five years, some US residents had access to and utilized their public libraries robustly while libraries disappeared all together in other.