Leslie Jamison on Writing and Her Newest Essay Collection

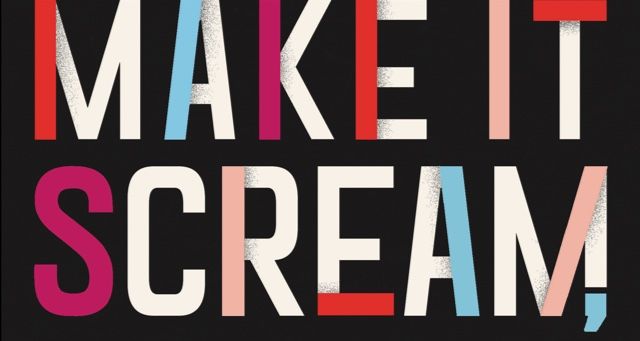

When I first read Leslie Jamison’s essay collection The Empathy Exams back in 2014, I devoured every essay. I then read her novel The Gin Closet, and have read everything she’s put out since. Her writing is sharp and observant, and her ability to move from fiction to personal essay to narrative nonfiction and memoir is admirable. I caught up with her via email to talk about her essay collection Make It Scream, Make It Burn, coming out September 24.

Leslie Jamison: These essays are just a portion of the writing I’ve done over the past seven years, and ultimately it felt important to me to put together a collection that felt purposeful rather than simply aggregated. As I started looking at the writing I was drawn to, I started to see these themes running underneath pieces that seemed quite disparate in their surface subjects: obsession, longing, haunting—all of these being ways of describing the ways we feel shaped by what we can’t possess.

JH: You state on your website that Make It Scream, Make It Burn is a mirror image to The Empathy Exams. Was this a conscious choice, or did it happen organically?

LJ: Make It Scream, Make It Burn is divided into three sections—Longing, Looking, and Dwelling—and across the course of these essays, it moves from an outward reportorial gaze to a more autobiographical vein of inquiry, closing with deeply personal essays about romance, family, and motherhood. In this arc, it functions as a kind of mirror to my first collection, The Empathy Exams, which began in a deeply personal place and then pointed this confessional gaze outward. Was this mirroring a conscious choice? Not from the outset. From the outset, with both books, I wasn’t writing with an aerial map in mind. I was simply following what fascinated me, what I felt a certain kind of urgency about writing. BUT, once I started to have a strong sense of which essays I wanted to include in this collection, I did become fascinated by the idea of sequencing them in a way that would invert the inward-to-outward logic of The Empathy Exams—that would effectively peel away layers from the journalistic voice to reveal what had been driving her fascinations.

JH: I know you’re the Chair of Columbia’s CNF program and a professor, and you also have a family. As a working mother myself, I’m always intrigued to hear how other parents (of any gender, but usually mothers, since many times it falls upon us to do a lot of the work) carve out a writing routine or space for themselves. Can you speak to what your routine looks like?

LJ: Some writers moan about getting too many questions about “process,” and I cannot relate to that lament in any way at all. I’m always hungry to hear other writers talk about how they work—and how they make space for their work—and am always glad to be part of that conversation, as well. I think it’s so important to demystify the writing process, to make it something daily and granular, to push back against the idea that logistics and inspiration are competing gods that live in different worlds. They both live in this one. One of my best friends and I like to talk about the work involved in fighting our way back to the “sacred clearing”—that space where the writing can actually happen, amidst all the childcare and the teaching and the grocery shopping. It’s simply a relief to acknowledge and articulate and hear others articulate that there is so much work involved in coming back to this clearing; and that sometimes you get there, and nothing much happens, and you have to believe in that part of the work too: showing up for the writing, even when it’s not going as well as you’d hoped.

To speak practically: paid childcare is a huge part of what makes it possible for me to write. I also do a lot of work during my toddler daughter’s naps, and after she goes to sleep at night. I’ve gotten very good at sorting work into different categories: “nap work” or “post-bedtime” often involves discrete tasks (like emails or workshop letters), while I preserve those precious stretches of longer hours for the creative work, when I can really dive in without being impossibly tired or uncertain when I’ll be called back.

JH: What are you working on now?

LJ: I am working on an essay about Garry Winogrand—there’s an exhibit of his color photography at the Brooklyn Museum that feels to me like a secular cathedral of humanity, in all its bewilderment and glory—and also feeling my way into another novel, for the first time in almost a decade!