Lesbian Pulp, Carmilla, and Reclaiming Toxic Representations

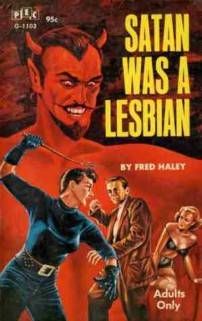

I have a book cover blown up and printed on canvas that hangs in a place of pride in my living room. It’s a book I’ve never owned, nevermind read. It’s a book that I can only guess, should I ever read it, I would hate. That book is Satan Was a Lesbian by Fred Haley.

This cover raises so many questions…

I love it, in all its ridiculous glory. The one collection I have is lesbian pulp books, and in addition to this decoration, I also have lesbian pulp magnets. I will happily spend $50 on a book that I may not ever read—and if I did, I would discover something written to be titillating and disposable. Not exactly high literature.

So why am I so drawn to these books? There’s a combination of factors: sapphic literature is my passion, and lesbian pulp plays a big part in that history. It also contains some gems: queer authors who were writing their own experiences, sneaking in positive representation and even happy endings whenever possible.

But if I’m being honest, a large portion of the appeal is the covers. They are so over-the-top that, for me, they blow right past offensive and into hilarious. They’re a caricature of how queer women are portrayed in the world. (I highly recommend checking out Strange Sisters if you want to see more of them.) There’s also something that feels powerful in reclaiming representation that was used against you. Queer women haven’t had a ton of representation in literature, historically, so any stories that we can get are precious. Even if they were meant to be negative, queer women have often been able to take them back and reinvent them into something positive.

Carmilla, by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, is a vampire novella that predates Dracula, and it’s pretty gay. Surprisingly so, for a book that’s hundreds of years old. This was definitely not written to be positive representation for queer women. So why is it so popular with queer readers? Why was it made into a successful queer web series (and now movie)?

For one thing, I think the novelty of a lesbian vampire who canonically predates Dracula is pretty cool. But another factor is that queer people have so often been associated with monsters and villains that sometimes, instead of letting that association make us feel monstrous, we reclaim monsters and villains. We find ways to see the villains as heroes. We pull apart a story to find the glimpses of the humanity in those monsters. Even the protagonist in the original Carmilla can’t quite condemn her. She still feels drawn to her.

Queer women have long been confined to the margins in literature. When we weren’t being ignored, we’ve been demonized or killed. It is only recently that we’ve been able to publish stories that are multi-faceted and representative of our real experiences. It’s unsurprising that we still have our old instincts when it comes to stories about us: dive deep to find subtext, spin to recast the monster as hero, and keep on telling our own stories, even when no one seems to be listening. It’s no wonder so many queer women write and read fan fiction more than traditionally published books.

Reclaiming toxic representation has been a survival strategy for queer women, and although positive representation is becoming more common, old habits die hard. Personally, I think it’s a very good sign that lesbian pulp has become an ironic, kitsch statement for queer women. If we can look at caricatures of ourselves, these condemnations from the past, and laugh, that suggests we are confident that those days are firmly behind us.