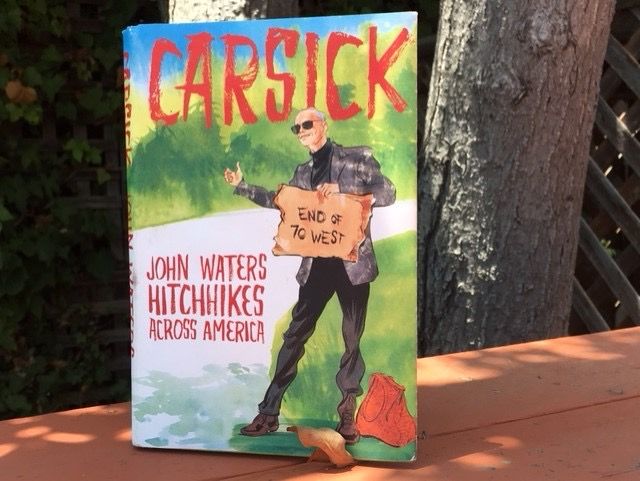

John Waters’s CARSICK: The Best Summer Road Trip Book

“FICTION. NONFICTION. THEN THE TRUTH. ALL SCARY. GO AHEAD, JOHN, JUMP OFF THE CLIFF.” —from Carsick by John Waters

Two details signify that summer has arrived: the dreamy scent from the full-blooming jasmine bush outside my window and the compulsion to read, once again, John Waters’s Carsick.

I was graced with reading Carsick four years ago upon its publication in 2014. I loved the idea of Carsick: the story about a solo hitchhiker, nearly 66 years old, taking to the open road. Somewhat like a Jack Kerouac adventure.

Except that John Waters is so much more fun than Jack Kerouac. And, when I considered my fantasy narrative about hitchhiking either with Kerouac or Waters, Waters easily won over Kerouac by a triple landslide. With all due respect to Kerouac and his people, I think that traveling when female with Kerouac would relegate me to the narrow role of Kerouac’s helper.

Now, with John Waters, just the idea of hitchhiking cross country with him brings delightful scenarios to mind. Like many bibliophiles and Book Rioters who would rather read about a fantastical road trip than actually take one, this John Waters book is for you. It contains every inventive and fascinating adventures too risqué to mention in polite company—but you will remember every tale.

It is Waters’s sublime prowess as a wordsmith, combined with his whimsical and imaginative stories, that keep the reader engaged and coming back for more thrills. Waters deftly places the reader into the action in every chapter and the reader becomes involved in the outcome of every scene. One may not have actually attended a demolition derby, but by Waters’s experiential tale of participating in a most unusual demolition derby, the reader becomes aware of the smells of blood and gasoline and fire and the nuances of derby demolition.

Besides being a witness to the glorious and perilous scenes of Waters’s life on the road, Carsick also provides a sound template for approaching life’s harder moments: the days when a commitment needs to be made.

When Waters received permission from his publishers to begin his cross-country journey and then write a book describing his journey, he was surprised at the reaction from his community of friends and family in the art and gay scene of Baltimore. His friends were not enthusiastic and actually quite fearful: there are the potentially fatal dangers of serial killers and homophobic attacks, stories of hitchhikers who, quite simply, just disappeared.

Waters needed a way to calm his fears as well. Was he crazy for thinking he could do this? Who was he, besides the much-beloved filmmaker, to think that he could possibly hitchhike alone across the country at 66 years old?

To calm his fears and those of his friends, Waters structured Carsick into three sections: the first two sections would be fiction, titled The Best That Could Happen and The Worst That Could Happen. And, finally, the last section, The Real Thing. The Real Thing would be the nonfictional, the true and factual accounting of Waters’s hitchhiking journey.

It’s like life: you imagine the best happening from your decision while being aware of the worst consequences and the reality proves to lie somewhere in between the best and the worst.

This is the great magic of Carsick: while imagining the very best that could happen, Waters is blessed with the presence of singer Connie Francis, finding lost actors from his movies, and a traveling librarian who delivers rare pornography to the rural readers unable to fetishize their tastes from the lack of porn stores in their area.

And where else but in a John Waters production would one be able to meet Kay Kay? Kay Kay is an earnest middle-aged white woman who simply wanted to learn how to drive. She was cursed with being assigned a driving teacher who was a warrior for the unborn, a psychopathic pro-lifer who berated and terrified poor Kay Kay. She wanted her privacy respected about the subject—it wasn’t her fault that she was forced to lock the driving instructor in the trunk to stop his ranting.

It was then that Kay Kay picked up John Waters on Interstate 70. She did not recognize Waters. The more pressing issue at hand was how to explain the persistent knocking coming from the trunk. “Kay Kay laughs for the first time, and I see that she really is a moderate person who was baited into a political fervor she never knew lurked inside her,” is how Waters described his encounter with Kay Kay.

That’s another thing I like about John Waters: his concern for social justice.

And I have often questioned my behavior over the last chapter in The Worst That Could Happen. Here is John Waters, examining the darkness of his worst fears and the potential of his own destruction as he hitchhikes across the road, and I am chuckling about his downward fear spiral. I chastise myself over my reaction to Waters’s vision of his last ride.

After leaving a multi-vehicle car-from-hell-accident outside of Las Vegas, Waters is offered a ride from Randy. Randy appeared to be okay as he called out in a deceptively solicitous voice to Waters from his truck. Within minutes, however, Waters realizes this may very well be his last ride. Ever.

“‘I hate all cult-film directors,’ Randy announces with bone-chilling seriousness.”

“‘Look, Randy,’ I groan through spasms of pain, ‘just let me out here. I promise I won’t make any trash films again—I’ll go make mainstream movies, I swear.’”

“‘It’s too late for a career change,’ snarls Randy with murderous rage as he pulls his truck off the road into an abandoned drive-in movie theater.”

The cliched white tunnel appears. Waters knows he will not reach San Francisco.

And Waters will not reach heaven, either. He does see Anita Bryant beyond the pearly gates, but, he is plunging downward. “I plunge into hell and see all my deceased friends, but they can’t see me or each other. It’s hotter than Baltimore in August. It’s a Wonderful Life plays on an extended loop on movie screens in every direction. I watch it for eternity.”

And then the reader reaches the last nonfiction section of Carsick, The Real Thing. Everything was fine. Waters reached San Francisco; his most vexing problem was standing for hours on Interstate 70 waiting for a ride in the rain. It’s like life, filled with quotidian details that must be addressed interspersed with the challenge of the day.

In the reality of his trip, Waters traveled beautifully and was treated with generosity and respect. There were some people that recognized him and those that did not. Waters did “not have one scary ride, not one car accident, not one incident of police harassment.”

“But more than anything, I’d like to praise the drivers who picked me up. If I ever hear another elitist jerk use the term flyover people, I’ll punch him in the mouth. My riders were brave and open-minded, and their down-to-earth kindness gave me a new faith in how decent Americans can be. They are the only heroes in this book.”

That’s another quality of John Waters I am so appreciative of: he is without pretension. And fun is a priority.