Is There a Time for Forgiveness?

I’m angry.

I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t angry, although I do recall handling my anger better in the past. Through my anger, I could see the human reality–the reasons that other people angered me–and embrace their human frailties. Bullies, criminals, the shockingly selfish: their actions might inspire rage, but after the storm it was easy to understand the motivations that drove their behavior, to accept their actions, and to find forgiveness, moving past the hurt.

And then, somehow, it wasn’t.

Unforgiving anger seemed to fester within me: city inspectors, other people’s relatives, my own friends, somehow every perceived wrong against my person conflated into a writhing miasma, a cloud over my own ability to view the world.

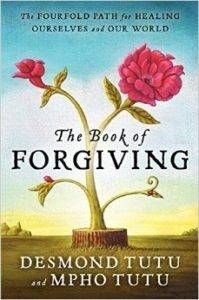

It was October of 2016 when The Book of Forgiveness by Desmond Tutu and Mpho Tutu practically fell off the library shelf into my hands. Perhaps Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Tutu had the answer. Through his work with the South African Truth and Reconciliation Tutu embraced the Fourfold Path: Telling the Story, Naming the Hurt, Granting Forgiveness, and Renewing or Releasing the Relationship. According to his writing, this practice allowed the victims of horrific violence and racism to heal and move forward with their lives. If the people of South Africa could forgive the decades of abuse, surely I could forgive the anonymous neighbor who reported my yard to Code Enforcement.

But it wasn’t that easy. Archbishop Tutu’s recommendations involved meditation, ritual, and journaling. More to the point, the descriptions of atrocities from which Tutu’s subjects managed to recover were so heinous as to make my complaints feel petty and pointless. Surely, if someone could embrace the killer who murdered their family, there must be something wrong with me to experience such overwhelming rage over something someone said.

And then the election happened.

Anger, combined with fear, became a driving focus, the fuel that powered the actions that prevented terrified impotence in a world spiraling away from meaning and values. Anger pulled introverts away from their screens and out into the streets to protest. Anger inspired art that inspired anger, and that anger felt justified. The options appeared to be anger or petrification, and forgiveness seemed equivalent with rolling over and condoning the worst abuses of government.

Not everyone, I learned in regard to Tutu’s recommendations, felt served by the Fourfold Path. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission still has its critics and detractors. Many South Africans wanted justice over reconciliation. Many survivors were sickened to know that abusers and murderers would receive amnesty.

I’m still making my way through the book, and I still believe Tutu when he explains the psychological benefits of forgiveness, but, for now, I think I need to hang on to my anger. Certainly, I can’t expect myself to forgive anyone who continues to escalate abuse.

There will be a time for forgiveness. I just hope it’s a time in the not-so-distant future, before there are too many abuses to forgive.