In Search Of The Lesser Told Lesbian Stories

Most of the books I have read with lesbian narratives I have stumbled upon by happy accident. One of the first was Miss Timmins’ School For Girls by Nayana Currimbhoy. Currimbhoy’s novel is a lush and smart account of a lesbian relationship between two teachers at an all-girls school in the hills of western India and the mysterious murder of one of the women. I fell deeply in love with the nuance and dignity the women were given to be individuals and lovers and the shrewdness with which Currimbhoy handled the mystery at the center of the narrative.

Finding books that center lesbian narratives can be difficult. They’re often rendered invisible and sold as something else. For example, I was thoroughly surprised when I picked up The Color Purple, expecting it to be just another book about a husband who beats his wife only to find that The Color Purple is definitely not that. The book is a lesbian love story, a reclamation for Black sisterhood, and an archive of the abuse that follows Black women.

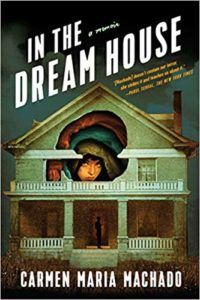

When I pick up Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House I know it’s about lesbians. Written as a series of portraitures, “Dream House as…” the memoir is a contribution to the severely lacking archive on lesbian experiences of domestic abuse.

Historically, cases of intimate partner violence in lesbian relationships have been hard to document or categorize. Abuse happens differently in lesbian relationships. According to a University of Missouri at St. Louis fact sheet on lesbian partner violence, “psychological abuse has been reported as occurring at least one time by 24% to 90% of lesbians.” The pattern, it seems, is that abuse isn’t quite tangible in lesbian relationships, making a situation that’s already hard to report with heterosexual relationships even harder to report.

Furthermore, there has been a silence in the queer community. A reluctance to show similarities with heterosexual relationships, a reluctance to admit that we have the same problems and are not absolved of guilt simply because of our queerness. A big part of Machado’s memoir is peeling back the veneer, that we are indeed human in our queerness and therefore given to the same human folly as everyone else.

Our lesbianism is not going to save us from violence.

I read it primarily because I’m a lesbian and because I am no stranger to domestic abuse. I grew up in a household where hitting came as simply as the sun rose. I am interested in stories about people who have been hurt by the people they trusted. Because those are the ones that hurt.

Like Machado’s In the Dream House, in The Color Purple Walker presents a contribution to a narrative that is so rarely catalogued and centered: Black lesbian love stories (with happy endings).

How many books on Black lesbians have you read? Go ahead, I’ll wait.

The Color Purple was important to me in much the same way In the Dream House is. Both books participate in silence breaking. But where The Color Purple is a work of fiction, Machado’s is a memoir of intimate details.

As I read it, traveling further and further into the intimate details of Machado’s life, I couldn’t shake the unmistakable sense of dread building in my gut. It was acutely stressful to read but once I started I couldn’t stop. It was over quickly.

I devoured the book the same way people stop to watch car accidents, to check if someone made it out of the wreckage alive. I read the memoir searching for survivors in the ruins of a life and a love.

Once it was over I could appreciate it for what it had been, not what it was. When you’re reading Machado’s details, you’re sensorily experiencing the story in the same state of anxious frenzy and distress that she is. It’s intoxicatingly exhausting.

I imagine it brings most people closer to experiencing the fear and anxiety of intimate partner violence. It is an intentional submersion, so you too can know what it feels like to be drowning inside something you didn’t even realize was an ocean.

In the beginning it was just two feet of water, how did that happen?

But when it was over?

I realized how fun it had been. Abuse is starkly not fun, but Machado’s voice and style as a writer is. She’s full of tongue-in-cheek invention and a playfulness that’s exerting itself just to show off a bit. But she knows you’ll like it. And how could you not.

You feel in on it too.

In the Dream House is a book you can’t wait to finish, but once it’s done you want to go back and have the conversation about the kinds of violence we accept and survive again. And indeed it is a conversation.

One we should have been having a long time ago.