Horror and The Women Who Write It

This is a guest post by Letitia Trent. Letitia is the author of the novel Echo Lake, published by Dark House Press in 2014, the full-length poetry collection One Perfect Bird, published by Sundress Publications, and the chapbook You aren’t in this movie, published by dancing girl press. Trent writes regularly for The Nervous Breakdown and the film magazine Bright Wall in a Dark Room. Her work has appeared in The Denver Quarterly, Fence, Sou’Wester, H_ngm_n, and The Adirondack Review. Follow her on Twitter @letrent.

____________________

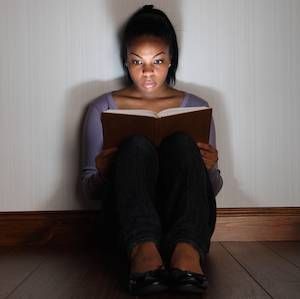

My tastes have always run toward the dark, toward things that I knew would give me nightmares, that I perhaps didn’t want to know but couldn’t help wanting to see. As a very young reader, I sought out books that elicited fear: Scary Stories To Tell In the Dark, RL Stine’s Fear Street novels, and many cheap paperbacks, names long forgotten, that I picked up merely because of their lurid covers—these were my early favorites. The first adult books I ever read, aside from my stepfather’s batch of Louis L’amour books and Wal-Mart dollar classics, were horror novels. Like many adolescents, I read Stephen King when I was far too young: the sex scenes in It were probably as shocking and new to me as the murders. Soon after, I discovered Shirley Jackson and felt a kinship with the isolated and fiercely independent narrator Merricat in We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Even after I started reading more literary fiction, I was mostly interested in darker visions of the world: The Bell Jar was my favorite book until I was well into my twenties, and I can still quote those evocative opening lines about the sultry summer in which they electrocuted the Rosenbergs. These early reading experiences not only shaped my desire to become a writer, but also the kind of writing I wanted to do. I, too, would look directly at darkness. Because so many of the writers I loved were women, it never occurred to me to question my own place in this tradition.

When I got my MFA in creative writing, my focus was initially poetry. By my second year, though, I wanted to try my hand at prose. I took my first creative writing class in fiction and announced that I wanted to write a vampire novel. I wrote that novel, and it was terrible (and will never see the light of day), but during the process, I started to delve into the online world of horror writers and horror writing forums. In my attempts to join that community, I started to realize that horror writing, despite the presence of female writers in the genre from Mary Shelley to Shirley Jackson to Anne Rice and many others, was still a bit of a boy’s club, specifically a white, middle-aged, middle class boy’s club. Even today, if you Google “best horror authors,” you’ll find lists with nary a female author (though sometimes Shirley Jackson makes the cut). If you look at the top horror novels on Amazon, the authors are overwhelmingly male (and overwhelmingly Stephen King, though that’s no surprise, since he practically created horror as a modern genre), and the few female novelists are often writing under their initials, not their full names.

What are these female authors afraid of, and why do they want to appear genderless? Many of those novels written by authors who use their initials are also categorized as “supernatural romance,” the one horror sub-genre that is dominated by women—and most frequently criticized and mocked by “serious” horror writers. Perhaps these writers want to escape being labeled as soft, as unserious, as unworthy of the genre title. After all, what is more damning than being labeled a writer of “women’s fiction?” Of all of the criticisms of Twilight and similar books, the one that seems the least fair is that these books take monsters and make them appealing to girls. In those early days of developing my voice as a dark fiction writer, the more I read about horror and the genre expectations from fans and fellow writers, the more I wondered if my writing might be too soft, too female for an audience that might judge my work as one more inferior example of the sub-category of “women’s horror.” Being a woman writing within this genre means you are constantly second-guessing audience perception and trying to figure out how to be taken seriously.

Once I dug beyond the mainstream surface, though, I found there was a great deal of diversity in gender, sexuality and ethnicity in the horror and dark fiction world. Small presses and magazines, such as Dark House Pres, ChiZine Publications, Apex, Strange Horizons, and Small Beer Press (among many, many others, many of which do not categorize themselves strictly as “horror” publishers) are not only publishing a far more diverse array of writers than traditional horror publishers, but they also provide a wider spectrum of what’s considered “horror”: literary dark fiction, dark fantasy, neo-noir, and speculative fiction exist side-by-side in some of these publications. Since the conventions of any genre are intimately connected with the culture and gender, it makes sense that widening the field might bring forth new and more diverse voices.

When we think of horror stories as being primarily about lone, male protagonists facing “evil” that must be defeated, it makes sense that certain writers might feel left out of the paradigm. Of course, horror has never been that simple. What better genre is there for turning conventions about gender, good and evil, sexuality, and society on their head than the genre that asks us to look at the darkest parts of ourselves?Women, as well as people of color and others who are culturally marginalized, have stories to tell that can transform and subvert existing horror conventions.Horror has subverted expectations about “monstrous” and “normal” or “evil” and “good” right from the beginning of the genre, and now compelling and diverse dark fiction writers are reaching more readers and expanding definitions of horror.