How Does the Harlem Renaissance Resonate 100 Years Later?

Before I can talk about how the Harlem Renaissance resonates 100 years later, there’s another question I need to answer: What was the Harlem Renaissance? Spanning from the 1910s to the 1930s, this period in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City was an explosion of Black art celebrating culture and decrying the injustices that Black Americans were facing daily. Poets, authors, musicians, and visual artists were all creating powerful works during this period, making Harlem the center of the Black art world in the United States for a time.

As our calendars turn over to 2022, we’re a century separated from the thick of the Harlem Renaissance period. How, after all this time, do the writings of this period still resonate today?

Growing Awareness

When I think of the position of the Harlem Renaissance in history, I see many parallels to today. The Great Migration occurred during World War I. During this time, Black Americans moved en mass out of the Jim Crow south and into the midwest, northeast, and western states. This period was the first time, Black Americans had the opportunity to be published. Numerous small publications and Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association in Harlem provided publishing opportunities that whites were not allowing Black Americans. Suddenly, Black writers were producing and publishing stories, poems, and essays like never before.

Today, we live in an era with an acute awareness of how white and hetero the publishing industry has been for, well, forever. Readers are choosing to decolonize their bookshelves and their reading lists, seeking out works by BIPOC authors. This shift in purchasing is slowly moving the needle for publishing houses. The process is slow, too slow, and we still have a long way to go, but we’re seeing more published works from Black authors than ever.

Double-Consciousness

Coined in 1903 by W.E.B. DuBois, “Double-Consciousness” is a term to describe how Black Americans are both Black and American at the same time, even though these two things are directly at odds with each other. “Double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others. One ever feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.”

Throughout the decades since, this sense of double-consciousness has been seen at work in countless American works by Black authors. Toni Morrison and James Baldwin wrote exclusively about the struggles of being Black in a country that hates Blackness. More recently, Angie Thomas has found success with her young adult novels, beginning with The Hate U Give. In it, Starr is a Black girl attending a mostly white private school when one of her childhood friends is murdered by police. Throughout the book, she has to navigate the worlds of her Black neighborhood and her white school and boyfriend.

Colorism and Other Cultural Divides

With the rise of Black literature in the Harlem Renaissance, Black writers started to publish explorations on their own cultural issues for the first time. Books and poems were no longer focuses solely on racial divides in America, but on the problems that occur within Black communities in America. Chief among these (at least, in the literary world) was colorism. In a country (and a world) that favors light-skinned people, this preference rubbed off on Black communities as well. Claude McKay’s story “Mattie and Her Sweetman,” the poems of Helene Johnson, and Nella Larsen’s novel Passing all deeply explored the differences in treatment between light-skinned and dark-skinned Black people, including how some light-skinned Black people chose to “pass” as white.

Fast-forward to today and these issues still exist and are still written about. Helen Oyeyemi’s Boy, Snow, Bird is a story of passing, and Oyeyemi has said directly that she was inspired by Larsen’s seminal book. Even more recently, Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half read like a modern-age Passing and dominated the bestseller list for weeks. A fairly straight line can be drawn from Nella Larson to James Baldwin to Toni Morrison to Brit Bennett, and modern Black authors know it. As Jacqueline Woodson said, “A renaissance is a continuum. We’re here because of the Harlem Renaissance. All of our work has come before in some way, shape or form.”

Behold the Black Queer Poet

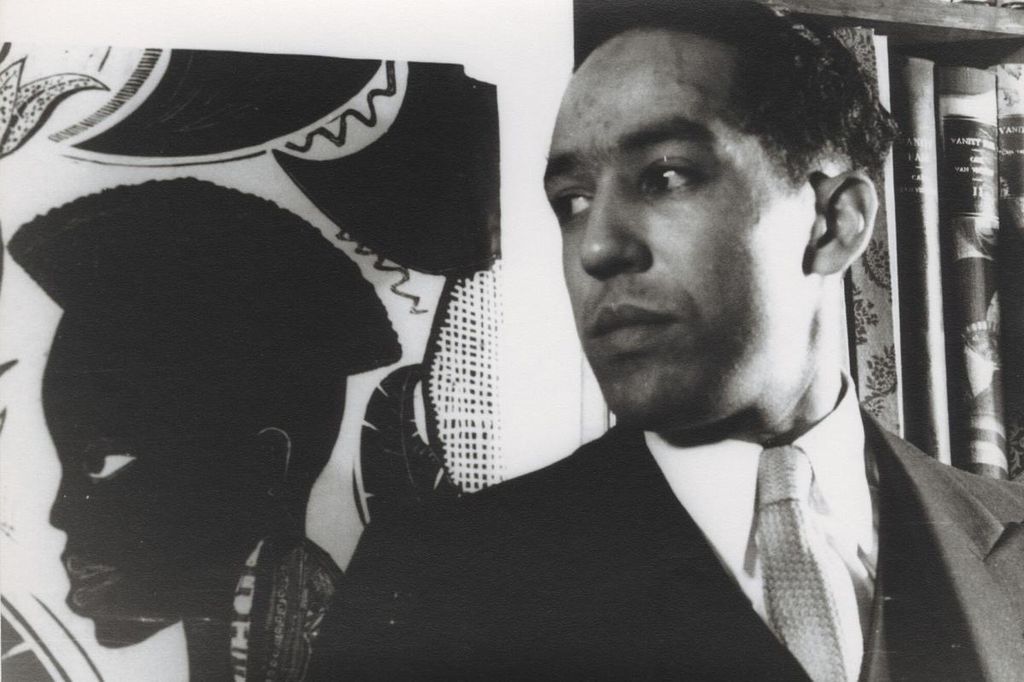

If you don’t know Harlem Renaissance poetry, then you probably don’t realize how very queer that poetry was. Names you may have never heard like Helene Johnson, Wallace Thurman, Alain Locke, and Richard Bruce Nugent were writing about their Black queer lives in coded, subtle ways (and sometimes in not-so-subtle ways). But so were names you probably have heard of, like Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, and Langston Hughes. Yes, THAT Langston Hughes, the most famous of all the Harlem Renaissance writers.

Since the Harlem Renaissance, some of the best poets and writers in America have been Black and queer. Robert Hayden, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Nikki Giovanni, Carl Phillips, and Danez Smith, just to name a handful. It was the Harlem Renaissance writers, in an era when being gay was nearly as fatal a condition as being Black, who paved the way for the incredible poets now who can write freely and openly about exactly who they are.

I leave you with a little homework. If you haven’t read some of the books and authors mentioned in this essay, please do. I also recommend Double-Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology by Venetria K. Patton and Maureen Honey and Legacy: Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance by Nikki Grimes. The tones of Black American writing today resonate on every page of those great Harlem Renaissance works.