Genre Kryptonite: Beauty and the Beast Retellings

Earnest preamble: I am fully aware of the dangerous, sexist subtext of the Beauty and the Beast story. The message that if a woman is truly good, she can change the nature of an angry, selfish, abusive man is a terrible one. The message that a good woman is valued for her physical beauty while simultaneously being expected to look beyond a man’s imperfections is a terrible one. These are not messages I would want any woman or girl to internalize. There are many powerful, important pieces of writing that detail or evoke exactly how incredibly problematic this story is, and I fully encourage everyone to read them.

HOWEVER.

In the spirit of unabashed Bad Feminism (™ Roxane Gay), I will admit that Beauty and the Beast stories are totally and completely my weakness, due to an early-age identification with the animated Belle (thanks, Disney!). I suspect I am in no way special in this regard. I have read or watched literally dozens of Beauty and the Beast retellings or adaptations (and for the record, turned out pretty great with lots of self-esteem and healthy relationships). The following is an evaluation of only a small handful of the bookish Beauties and Beast stories of my fictional acquaintance.

Rose Daughter, Robin McKinley

Robin McKinley is an amazing, magical weirdo and this is basically a book about gardening. It is about Beauty growing roses, then not growing roses for a long time, and then growing them again at the end. When it is not about Beauty growing or not growing roses, it is about her fantastic cross-dressing, horse-training older sister, Lionheart (a character who needs her own book STAT). When it is not about the roses or Lionheart, it is kind of about Beauty and the Beast.

This Beast, as it turns out, wasn’t cursed because he was selfish or cruel, but because he is actually a wizard whose magical theories were getting too real for the wizarding Establishment. His lack of a terrible flaw, sensitive, artistic sensibilities, and basically mild nature seem at odds with the very fact of his taking her prisoner in the first place, and make for a very strange Beast. Not quite as strange, however, as the solution to the not-growing roses which (spoiler!) turns out to be part “true love” and part “golden unicorn fertilizer.” I kid you not (see above, re: magical weirdo). This kind of thing is why I never regret reading a McKinley, even though this slow read isn’t my favourite retelling of the Beauty and the Beast story.

Dark Triumph, Robin LaFevers

When Beauty Tamed the Beast, Eloisa James

An unwed, pregnant bride, however, is exactly what Piers’s father, the Duke of Windebank, believes he needs, so the Duke strikes a deal with Linnet’s father and suddenly she is packed off to live in a remote castle with a famously grouchy, impotent man. Seems legit! A+ parenting there, guys. The fact that Linnet is not exactly the Beast’s prisoner so much as an essentially ruined woman with nowhere else to go makes the romance and eventual steamy interludes much more palatable, but more importantly, it’s interesting commentary on the limits of female agency in the oft-romanticized Regency era. By making the technically-still-virginal Linnet a social pariah, James subtly underlines how unmoored the concept of “sexual purity” is (and always was) from reality, and highlights how much of this incredibly important standard of judgement was outside a woman’s control. To top it all off, this version of the classic story even gives the “Beast” character an opportunity to demonstrate his lack of superficiality.

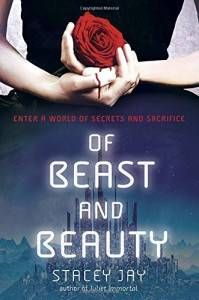

Of Beast and Beauty, Stacey Jay

As for the question of who is “beastly” in terms of physical appearance, well, that is slightly more complicated. Suffice to say that even though each of the two characters finds the other repulsive at the beginning of the story, neither of them are truly monsters. In Jay’s book, beastliness is tied up with issues of race and otherness: both characters discover that when you are taught from a young age to view the Other as less than human, virtually any action they take can be used to support your view of their monstrosity, and any between you and the Other is cause for self-loathing.

____________________

Book Riot Live is coming! Join us for a two-day event full of books, authors, and an all around good time.