Let’s Talk Folk Horror and Appropriation

CW: Some discussion of suicide

There’s an elephant in the room with folk horror, one that a lot of people find easy to ignore: cultural appropriation, especially that of Indigenous cultures.

How many horror stories end up with a setting being built on an “Indian burial ground,” with that being the reason misfortune befalls the main characters? And how many stories have we made w*ndigos the big bad in, which is something that Indigenous individuals have repeatedly asked us not to do? You see these spirits used in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary, Nick Clausen’s Human Flesh, several of Algernon Blackwood’s books, Donners of the Dead by Karina Hall, not to mention the multiple TV shows and movies that use them.

Now, I’ve written about topics like this before, especially why we should stop using Indigenous mythological creatures that are essentially the embodiment of pure evil. That’s why I’ve been censoring the name. It works a bit like sympathetic magic, by saying the name or even writing it, you draw the attention of the spirit. Regardless of your beliefs, drawing the attention of the pure embodiment of evil to you isn’t the best idea, and censoring the name is a small thing to do in the name of respect. We really shouldn’t conflate the creature with a mental disorder, either. This is in part because doing so would mean that every iteration of these spirits used is stripped of any and all cultural context beyond “it’s an Indian monster” and become basic stereotypes of what mainstream culture thinks these beliefs are. By reducing a culture’s belief into a mental illness, especially a mental illness that only affects members of that culture, you are only cementing harmful stereotypes plaguing the group.

Although Indigenous cultures are perhaps the most common ones Americans take from, they’re not the only ones we appropriate. Remember the movie The Forest, with Natalie Dormer, way back in 2016? The entire movie is based around Aokigahara, a national forest in Japan that has also been unfortunately called “The Suicide Forest.” Beyond the more modern practice of people walking into the forest with no intention of walking back out, local legends also say Aokigahara was once where ubasute was practiced. Ubasute was the practice of leaving sick and/or elderly relatives to die in times of shortage to relieve the burden on the family.

But that doesn’t mean we can make insensitive horror movies about it like we did with The Forest. We need to quit with stories that rely on “this foreign culture is strange and magical,” especially with horror stories where we also have to make them creepy. And when the cultural tidbit we decide to pull from heavily involves suicide and mental health, it’s especially damaging.

Other cultural practices that white mainstream has damaged by appropriating in the name of entertainment are santería, voodoo, and hoodoo, just to name a few. We need to pump the brakes with the cultural appropriation in general. It’s one thing to draw inspiration from a culture while also paying homage to it, if the culture is given the respect it deserves. It’s another to pull parts directly from a culture, stripping them of all context — leaving them a pale mockery of the culture they’re from — all in the name of horror. We need to learn to respect other cultures’ requests of leaving their belief systems alone, as we have no right to them.

And it’s not as if there aren’t plenty of cultures for us to actually pull from, as white people. No, there’s not a “white” culture, but there are still American cultures that can be used for folk horror stories. Appalachia alone has plenty of folk stories and monsters that could be made into folk horror movies or books. You have the tailypo, the wampus cat, Mothman, the Bell Witch, and let’s not forget the many Jack stories.

That’s just Appalachia too! That’s not including the United States’s many lake monsters (there’s nearly one per lake, seriously), the Jersey Devil, the Devil’s Hole Cave, and more. There are plenty to choose from that are not part of a culture we tried to wipe out. Moving outside the United States, there’s Celtic folklore, which is full of horrifying faeries. No, not little ones like Tinkerbell, I’m talking red caps (goblins that get their name from their red hats, which are red because they dip them in the blood of their murder victims), kelpies, sluagh (undead faeries), changelings, or Fear gorta, (Irish Gaelige for “man of hunger,” a faery that spreads famines).

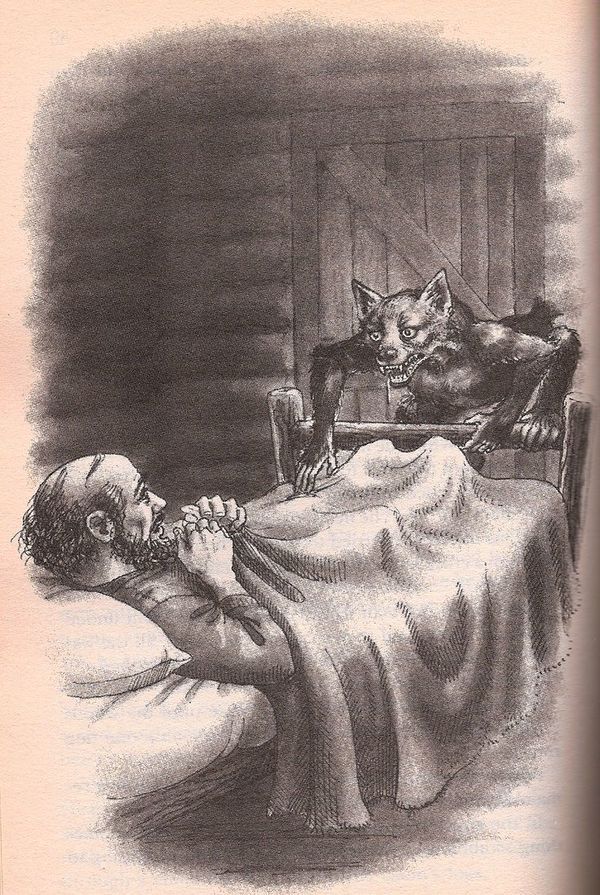

Moving onto continental Europe, a historical horror with la Béte du Gévudan, a man-eating wolf (sometimes werewolf, depending on the story) that terrorized Gévudan in the mid 1760s would be amazing. Everyone loves a good monster story. Or you can go Slavic, making horror stories around Koschei the Deathless from Russia (which would not be a difficult task), any number of Slavic demons from Poland or Ukraine, all of which could be set against a frozen wasteland. Remember The Thing (1982)? Frozen wastelands are excellent horror settings.

The point being, there are a lot of options for us to use for folk horror that aren’t cultural appropriation. That doesn’t mean we can’t be appropriative of the cultures and folklore I’ve listed. We just need to be mindful not to strip the context from any aspect of a piece of culture, and leaving alone cultures that we haven’t been the kindest to in the past is a good start.

If you’re looking for a good place to start with folk horror books, and maybe a primer on the genre itself, I recommend checking out our list of folk horror books.