Brown For No Reason: Finding Books When Brandy Cinderella is Your Lodestar

For as long as I have been a Professional Book Person, I have had both a personal and sociopolitical stake in diversity and equity in the publishing industry and literary content. I have, like many of us, huge problems with whitewashing, with inauthentic or insensitive portrayals of nonwhite (or other non-majority groups) people, with stereotypes. I don’t think all things must be #OwnVoices to be good, but I think a lot of stuff should be when possible.

Toni Morrison famously criticized the failures of the “white imagination,” a subconscious viewpoint of white creatives wherein they seem to be literally incapable of imagining the very existence — let alone the thriving or full being — of people of color. This sometimes leads to the Rue problem, or, y’know, just a publishing landscape that remains overwhelmingly white in professional makeup and literary content. That’s problem A.

As for B? There is something I like to call the Black Barbie Problem: you take a thing that is White As Default, and, to make Social Justice Warriors™ happy, you dip it in some brown paint and call it a day. Hooray! Racism is fixed. Except Black Barbie does not have any features typically associated with a different racial group or have any other markers that make her nonwhite except her skin tone (of course features vary; not all X people look the same, etc, but I hope you can see my point; please don’t @ me). Or, in the case of a story, your Black Barbie character lives in a real life American city but does not ever have to contend with her race, doesn’t have to deal with people trying to touch her hair, doesn’t experience microaggressions…puh-lease. Now that is science fiction.

You may think I’m being oxymoronic here — you don’t like the people of color in the books you’re reading, but you don’t want books without them, so which one is it?

Yes. (As in, do you want cake or ice cream? Yes.)

It will forever baffle me that in science fiction and fantasy, genres where you can literally make up an entire world from scratch if you want to, remain so white, both in content and context — that is, there is not a whole lot of SFF based on our real world that has people of color in it, and yet we don’t have a whole lot of Black Barbies in completely made up worlds, either. The publishing industry routinely and institutionally excludes people of color, but that’s a different article. Dragons, talking snowmen, humanoid plants, all fair game, but so many of the people interacting with these creatures are still flaxen-haired and blue-eyed? Bo-ring.

How long did it take Disney to get to The Princess and the Frog, and when they finally gave us Tiana, their imagination still could not extend to making up a fantasy world just like Aurora, Ariel, and Snow White before them: they had to put her into the real United States, had to make her experience a lot of racism in her real world, then experience meta-racism from her creators by being turned into an animal? In a genre where every other entry is a romp through a made-up kingdom? It was like holding out a treat and then snatching it away at the last minute — “ha ha, you thought you were joining our club, but you’re actually second-tier!” I am not consoled by people who tell me something along the lines of “but Disney is so problematic for XYZ reasons; you shouldn’t want to be included in that.” Because I do. I really do. Like it or not, that stuff is integral to our pop cultural identity and modern myth-making in the western world. We all deserve to be a part of it.

Every day I leave my house, I have to be conscious of the way my phenotypical appearance and cultural identities will affect the way people see or treat me, what they expect of me, what they assume about me…but that’s what they are putting on me. On my end? In my head? I’m the star, and I want to be treated like it. I want to see people like me existing without boundaries or barriers. Too many white creatives think you can’t have a character of color in a story without justifying it (and that too often manifests in casually racist ways) — I, however, wake up every day and am brown for no reason. Truly! No reason at all! I just exist!

White readers get to see themselves in the real world and in the fantastical, in the highfalutin Literary Works and in the Lowbrow Stuff, and everywhere in between. Readers of color deserve the same, and I’m here to argue that we don’t just deserve fantasy worlds based on the myths, fairytales, and legends of the non-U.S. places of our heritage or origin (such as Nnedi Okorafor’s Zahrah the Windseeker or Julie C. Dao’s Forest of a Thousand Lanterns). Critically, we deserve to see ourselves in “traditional” fantasy worlds — that is, worlds that are ostensibly generic but actually Euro- or Anglo-centric, because that, too, is the society we have to exist in on the daily. You want to colonize us? Then you have to include us.

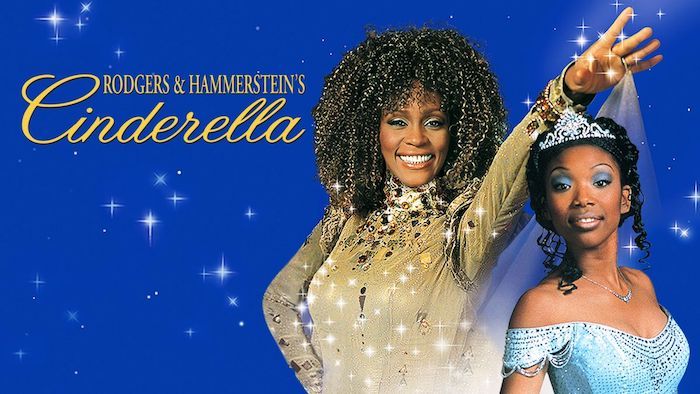

Enter Brandy Cinderella

Ironically, this 1997 groundbreaker was also a Disney production, but it’s Wonderful World of Disney, not a 2D animated feature, and that’s an entirely different institution, and I don’t have time to explain capitalism and monopolies right now. It was, however, everything I needed. A television movie based on Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella, this was a Broadway nerd’s multicultural dream that appealed to all ages and demographics. Jason Alexander basically played George Costanza, but working for a king! Who was Victor Garber! Garber and wife Whoopi Goldberg had a Filipino son! Who falls in love with R&B’s princess, Brandy! Whose fairy godmother is Whitney Motherflipping Houston! And Bernadette Peters is there for good measure! And nobody said a damn thing about any of it, because who cares? It’s fantasy, and all you need to be is a good singer! (This is why I was not impressed with Hamilton — somebody did all that stuff 20 years earlier, Lin-Manuel.)

Brandy Cinderella (that may not be its title on IMDb, but that’s definitely its more recognizable moniker) was, quite literally, the only fantasy story I had in my youth where somebody was brown for no reason. It’s absolutely flawless and I will accept no criticism or challenges to that statement — again, don’t @ me — but it’s not good enough to have just one. One that is almost old enough to rent a car without paying an extra fee, at that. Until about five seconds ago, you couldn’t stream it anywhere, and your only hope was that your best friend’s neighbor’s older brother taped it the night it aired and you know someone who still has a VCR. The soundtrack has, to this day, never been released for sale!

There is room in my library and in my heart for many types of SFF with diverse characters, but right now, I want the type that is absolutely Disneytastic. No real-world context, no racism, just Brown For No Reason in a made up world that is identical to the worlds I was shown on TV screens and bookshelves my entire childhood.

I have only ever found a handful of novels that fill this gap, all of them for middle grade readers (which is good and important! but not enough), and almost all of them written by white people, like Princeless and Twinchantment. On the one hand, that’s wonderful–white people should not be let off the hook on this issue. They are also, realistically, the people more likely to have power, status, and access in the publishing world (even Brandy Cinderella was produced by mostly white people), so we need them committing to the work. But there is a ton of room for nonwhite authors, members of various diasporas and living in colonized lands, to write ourselves into the world we have always lived in but never been fully welcome in. Sometimes we should be allowed to be brown for no reason at all.