My Evening with Margaret Atwood

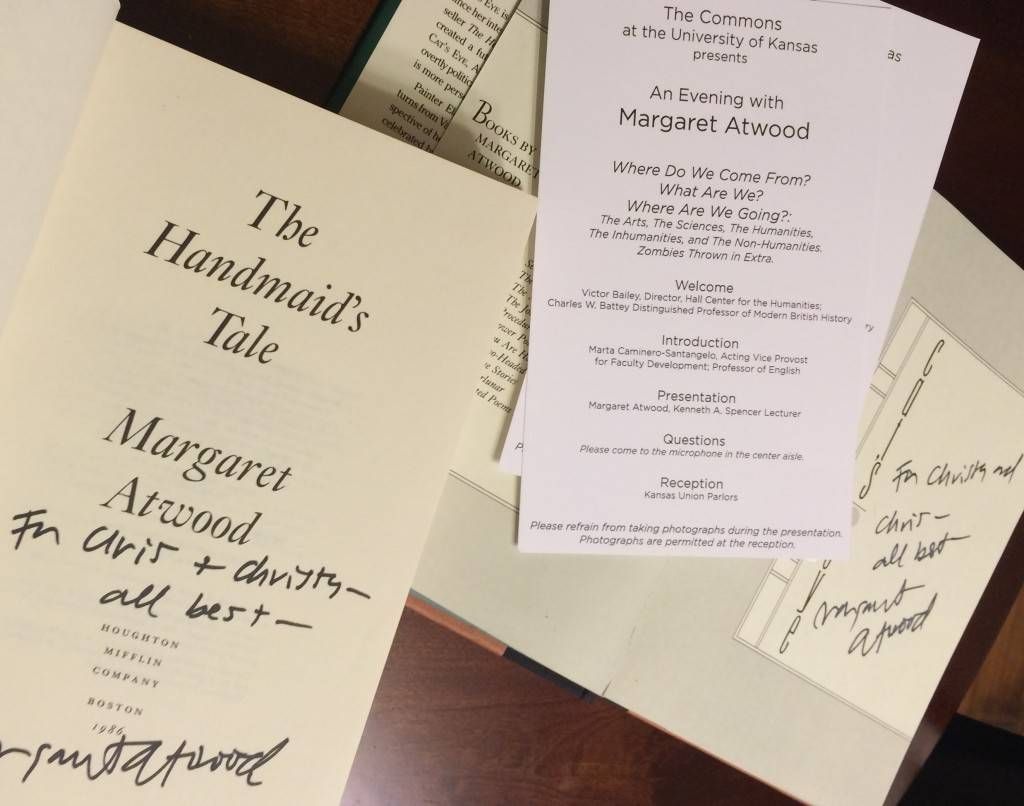

Margaret Atwood, though small in stature, is a towering figure in literature. Her books are deep, entertaining, and read for both pleasure and study. On the evening of February 2, 2015, I had the pleasure of seeing her speak on the University of Kansas campus. Her topic: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?: The Arts, The Sciences, The Humanities, the Inhumanities, and the Non-Humanities. Zombies Thrown In Extra.

If the zinger at the end of her title wasn’t enough, her first words certainly assured the crowd that this would not be some dry academic speech, “Can you see my tiny head?”

I’ve read a fair amount of Atwood and follow her on Twitter, so I certainly expected wit and vast intelligence. Her humor, however, was a treat. She joked about the Wizard of Oz (because we were in Kansas) and smoked whale testicles (you read that right). I learned that “beavering” is a verb, but not a dirty one, at least not in the context of writers working on the upcoming HBO adaptation of her MaddAddam trilogy.

After several wonderful minutes of her delightful humor with deadpan delivery, she got to the crux of her discussion: the blending of her love of sciences with her passions for literature and art. The first of three pillars of her discussion: Where do we come from? She talked about discoveries of art dating back hundreds of thousands of years and children being born with an innate sense of rhythm; how they draw on wall with crayons before they are ever taught concepts of “art.”

She morphed the question of “What are we?” into “Who are we?” Scientists drill down the “what” into DNA patterns, carbon-based lifeforms, etc. So “Who are we?” is the more important question. Anthropologists and theologians might argue into the night on this question, while literature students may quote Shakespeare’s Hamlet, as Atwood did:

What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals—and yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust?

Atwood then paid reverent homage to Wikipedia as she discussed the differences between the humanities and sciences, how they perceive the world. She then boiled down the difference splendidly: “The humanities are not rocket science, though they may explain an interest in rocket science.”

The final pillar of her discussion was “Where are we going?” She summed it up by quoting Dickens, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” The best can be seen in amazing inventions and advancements, particularly in genetics, that seem to be announced on a daily basis. The worst is apparent in global warming which has led to erratic weather which will lead to food shortages which will lead to political unrest and so on and so forth. Science can tell us that. Art makes it visceral and personal. Art gives us the man behind the curtain, pulling the strings that make the world worse.

That’s where the zombies came in. Zombies, according to Atwood, are a “modern, plebeian phenomenon.” They are pure metaphor for the end of the world, for the plight of the common man, but they also represent hope. You can shoot a zombie in the head, after all. You can’t fire a gun and fix the melting ice caps.

After her wonderful talk and a bevy of applause, she took questions. She discussed the Future Books Project because a certain bearded Book Riot contributor asked her. She explained the project and explained how all books are time capsules. To her, the Future Books Project takes that time capsule idea and extends it in very hopeful ways. It supposes that in 100 years there will be books, trees, a library, and a desire to still read books. That is why she immediately agreed.

Atwood traded witty barbs with a KU professor when he asked her why she chose literature. She talked about not really choosing it, how her family disapproved, and how she kept a day job for a long time. “Nobody would have chosen (literature) in 1956 in Canada,” she explained. She proceeded to tell the tale of trying her hand at true romance novels first, but never finding the “proper language” for it.

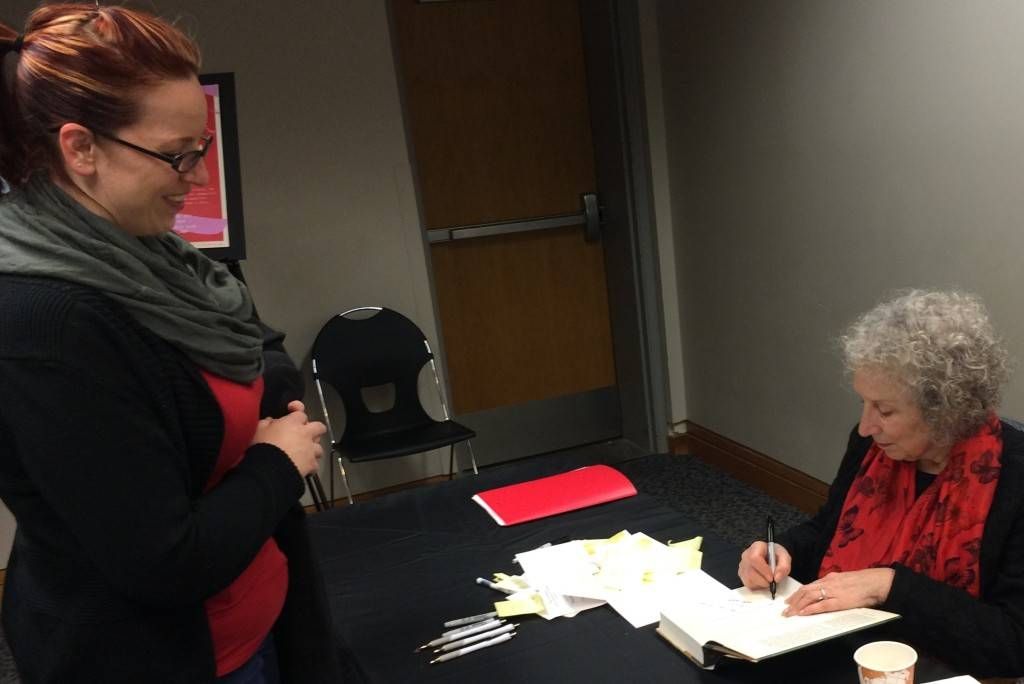

Finally, the more than 1,100 people amassed were ushered out of the room and into a very, very, very long line to get our books signed. I had brought ALL of my Margaret Atwoods, but stuck to their rule of one per person. Fortunately my wife came along (who now loves Margaret Atwood, too), so I had Atwood sign my copies of The Handmaid’s Tale and Cat’s Eye.

She was lovely, if rather exhausted by the time I got to see her and have a picture taken. My wife and I drove nearly an hour each way to see her speak, and I would gladly have driven much further for this delightful, brilliant woman.

____________________

Follow us on Twitter for more bookish goodness!