Edith Wharton: Horror Writer

Edith Wharton was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1921 for her novel The Age of Innocence. She is also known for her other novels, such as Ethan Frome and The House of Mirth. I love her short stories, especially the classically popular “Roman Fever.” She is a writer of great renown, though many readers might not realize that Wharton also wrote ghost stories, and damn good ones at that.

Wharton herself used to be terrified of ghost stories, having admitted to burning books on the subject for fear of having them in the house. Yet she slowly began to read ghost stories, and then she began to write ghost stories. Stories where you can feel the heavy winter storms and dense fog imprisoning you to a frigid, dark house. Stories where we question our sanity and our senses. And these haunting, spectral tales are what I love most about Wharton’s body of work.

The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton

Some of her most famous ghost stories include “The Lady Maid’s Bell” and “Pomegranate Seed.” For those who know of Shirley Jacksons’s hefty public feedback to the famous story “The Lottery,” published in 1948 by The New Yorker; Wharton experienced a similar bout of feedback for her story”Pomegranate Seed” much earlier, when the story appeared in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1931.

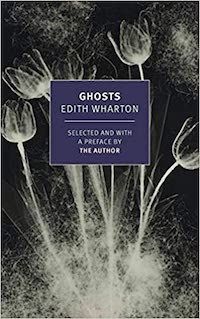

In the preface to her collection of stories, aptly titled Ghosts, first published in 1937 and recently re-published in its original format by NYRB, Wharton wrote:

…I was bombarded by a host of enquirers anxious, in the first place, to know the meaning of the story’s title (in the dark ages of my childhood an acquaintance with classical fairy-lore was as much a part of our stock of knowledge as Grimm and Andersen), and secondly, to be told how a ghost could write a letter, or put it into a letter-box.

“Preface” from Ghosts by Edith Wharton

Both Shirley Jackson and Edith Wharton have a knack for stirring discomfort and awe in the deepest recesses of our souls, and it seems they both have a knack for stirring it well enough that people felt the need to write them anxious — even angry — letters. What I deeply admire about Wharton’s ghost stories, much like Jackson’s work, is the way she portrays the chilling eeriness in mundane activities and shows just how warped the domestic can be. Wharton takes many houses (with wonderful names I might add: Kerfol, Lyng, Bells, etc.) and makes them dreary, cold places, despite their size and opulence. She takes what many would consider “normal” people, farmers, quiet widows and widowers, secretaries, etc. and makes them suspicious, haunted, and even bewitched.

Productive Ambiguity in Edith Wharton’s Horror

Wharton is brilliant in that she inherently trusts the unknown to her readers, which depending on the reader’s acceptance of the uncanny, often makes the stories more terrifying. She wrote in her preface:

When I first began to read, and then to write, ghost-stories, I was conscious of a common medium between myself and my readers, of their meeting me half-way among the primeval shadows, and filling in the gaps in my narrative with sensations and divinations akin to my own.

“Preface” from Ghosts by Edith Wharton

Not everything is explained in Wharton’s stories. Some readers may not enjoy the ambiguity of her endings. Not every sound and feeling is analyzed down to its minute crumb. Some stories end with terrible revelations and what-ifs, while others exhale in a soft, eerie whisper. These are not slasher nor cosmic horror stories; there is a lot of mundanity to Wharton’s settings, and her characters often take pride in their normalcies, their routines, and not having adventurous lives or lurid affairs.

Still, in the shadowy corners and lonely halls of these places, something is just not quite right. Wharton leans into some of the most simple fears and hones in on them: abandonment, loneliness, or being responsible — even inadvertently — for a small event or occurrence that then costs someone their life or livelihood.

While I could easily be tempted to write a thesis-length essay on Edith Wharton’s entire ghost story oeuvre, many have already done so. Her most famous stories, such as “Afterward,” “Pomegranate Seed,” and “The Lady Maid’s Bell,” have been anthologized and pored over many times (and rightfully so). Instead, I will simply touch on my favorite ghost story in the collection and how this one in particular unsettled me.

“All Souls”

Fear of abandonment is so well-developed in the first story in Wharton’s collection. Being confined or trapped in the home is a habitual theme among Wharton’s stories. It is a common fear and a primal one. In “All Souls,” the main character Sara Clayburn is walking back to her house, Whitegates, when she meets a woman on the way. What’s peculiar is Sara doesn’t recognize this woman, and she knows most in the area, and when asked where the woman was going, she answers, “‘Only to see one of the girls.'” After the meeting, Sara falls and injures her ankle. She is told not to walk on it and confined to bed. Her servant, Agnes, leaves her a tray of food, which Sara also finds unusual, knowing she could ring her if needed.

It’s a perfect storm for a horror story, because there’s also an actual snow storm, and Sara is not used to being idle. The night after her injury she counts down the hours till morning, the silence deafening, and what was mundane before suddenly becomes eerie and suspicious. Sara’s imagination runs wild:

“Who that has lived in an old house could possibly believe that the furniture in it stays still all night? Mrs. Clayburn almost fancied she saw one little slender-legged table slipping hastily back into its place.”

Morning finally comes, but the silence remains. Sara rings for Agnes but she does not come. The snow outside is blinding. The food tray Agnes offered but Sara scoffed at is now out of reach. The day goes on.

The story turns into a quest of sorts: Sara searches the house for her servants — Agnes is not there, the cook did not come, the handmaid’s room is empty — and for answers, wondering whether she was abandoned, trembling with fear and the pain on her ankle. Was she forgotten? Was this all planned? It is the emptiness of the house that is the worst of it. Her own house becomes a stranger to her, and is that not scary as hell, to view our own home as the villain?

And like other horror stories and movies that unsettle me, somehow the day passes, and the next day Agnes and the others arrive, and act as if nothing unusual has happened. The day of emptiness and a very strange occurrence (which I don’t want to spoil) that Sara endured is written off as a side effect of her painful injury. The doctor that arrives to check her ankle is different than the doctor that originally attended her. It’s that god-awful feeling of everyone being in on the joke but you.

The story comes full circle. A year passes. Sara Clayburn tells the narrator of this story of what happened. Then, a year to the day, on All Souls’ eve, Sara meets the same woman on her walk back to Whitegates. The woman is walking to the house, same as she was a year before. And she responds to Sara’s question with the same answer. It’s refreshing because Sara absolutely makes the connection and gets the hell out of there, and there is a hint that Agnes did know something else. Sara tells the narrator:

“And as I watched her I could see a little secret spark of relief in her eyes, though she was so on her guard. And she just said, ‘Very well, madam,’ and asked me what I wanted to take with me. Just as if I were in the habit of dashing off to New York after dark on an autumn night to meet a business engagement! No, she made a mistake not to show any surprise—”

With Wharton’s expert productive ambiguity though, there is no confirmation. There is conjecture, even mention of witches at the end of the story. But nothing is confirmed in absolute. Sara does not go back to Whitegates.

Wharton plays gloriously with the fear of being trapped in our own home. She uses gaslighting by secondary characters, deep pain from injury, and a snowstorm to set the scene of perfect unease. I still think about this story, especially the line about the furniture moving at night, and quiet nights blanketed in snow will never feel quite the same.

Among Primeval Shadows

For stories in the collection that similarly made my hair stand on end, “The Triumph of Night” and “Bewitched” (the dialogue in this story, holy cow) have also possessed my thoughts like small slivers. There’s just something about about a good horror story that haunts me in all the best ways. I enjoy picking apart Edith Wharton’s lines and choices as much as reveling in the discomfort she made me feel. It’s why I also wrote about horror literary magazines and their amazing short fiction that still rings in my head. You can also find some excellent horror short story collections to get you through the winter months.

Edith Wharton lamented in her Preface that the ghost story might very well be on the decline. She believed ghosts rely on silence, and modernity was putting an end to that. But I think she would take heart in the ghostly stories published today by the likes of Tananarive Due, Mariana Enríquez, and many others. After all, as Edith Wharton said of ghost stories, “if it sends a cold shiver down one’s spine, it has done its job and done it well.”

Wharton’s stories continue to send shivers down my spine, as does much contemporary horror short fiction. Which is to say, horror stories — ghost stories — have done and will continue to do a very damn good job.