DC’s IDENTITY CRISIS, 15 Years Later

In 2004 I was working part time at Borders (RIP) and just getting into comics. My manager at the time was also a big comics fan, and one day in the break room he lent me the first issue of DC’s big new event, Identity Crisis.

I now believe that Identity Crisis is one of the worst things that ever happened to the comic book industry, and we’re still shaking off its effects. But what made it so captivating—and so bad—and what were those effects?

Content note: the following contains discussion of fictional sexual assault and real world sexual harassment.

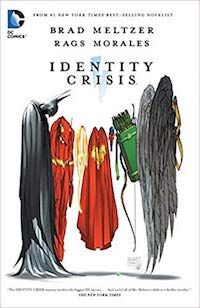

First, some background. Identity Crisis was a seven-issue miniseries written by novelist Brad Meltzer and drawn by Rags Morales, published from June to December of 2004. It entered the sales charts at #1 with 163K units preordered and finished out its run at the #3 spot with 140K units, which shows a remarkable lack of attrition. The first issue went back for two additional printings. DC currently sells three different versions of the trade, one with a list price of $103.98 at the time of this writing.

If you haven’t read it, here’s a brief, spoilery summary:

In the first issue, Sue Dibny, the wife of beloved comic relief hero Ralph Dibny, aka the Elongated Man, is murdered. The surviving members of the “Satellite Era” of the Justice League, i.e. the ’70s run—Green Arrow, Black Canary, Zatanna, the Atom, and Hawkman—assume Dr. Light is the killer and try to bring him in. When two younger heroes, Kyle Rayner (Green Lantern) and Wally West (the Flash) question why the JLA is targeting a villain widely perceived to be a hapless joke, the Satellite Era Leaguers reluctantly explain that back in the day, they occasionally used Zatanna’s magic to erase the memories of any villain who discovered their secret identities. One day, Dr. Light managed to sneak aboard the satellite, where he found Sue on monitor duty and raped her. When the League returned, they decided that wiping Light’s memory wouldn’t be enough, and voted to magically lobotomize him, making him incompetent ever since. Also, Batman, who wasn’t part of the initial vote, caught them at it and tried to stop them…so they wiped his mind, too.

The League fails to apprehend Light, who regains his memory and…full capacity of his brain? Unclear. Meanwhile, an anonymous figure attacks Jean Loring, the Atom’s ex-wife; sends a threatening note to Lois Lane; and hires the villain Captain Boomerang to kill Jack Drake, the father of then-Robin Tim Drake. Boomerang and Jack kill each other, leaving their sons orphaned. Elsewhere, the hero Firestorm is killed while questioning other suspects in Sue’s murder.

An autopsy reveals that Sue died of an aneurysm, and close examination reveals tiny footprints on her brain. Simultaneously, the Atom, who has gotten back together with Jean after rescuing her from her mysterious attacker, realizes she knows more than she should about the various attacks…meaning that she must be the killer. She tearfully confesses that she borrowed his equipment but insists that she only meant to scare Sue, hoping that threats to various Leaguers’ loved ones would send her own Leaguer straight back to her arms. The Atom has her committed to Arkham Asylum, then wanders off to be tiny and sad for a while. Meanwhile, Batman starts to suspect (correctly) that the rest of the League has been playing with his memory, causing an erosion of his trust in them that cause a domino effect of negative consequences in future stories.

The end!…Hooray?

There are a lot of minor issues with this story. Like most Crises, it slaughters a number of tangential characters to show you that it means business—like, I don’t care about Firestorm, and he’s back now anyway, but he deserved better than that. Most of the cast is written fairly out of character, and the bulk of the story is narrated by Green Arrow, a baffling choice for a story about secret identities when he hadn’t had one in 20 years. And the pacing is a mess: with the murder in #1, the backstory in #2, and the reveal in #7, that’s four whole issues in the middle of treading water with the heroes coming no closer to the solution while a bunch of people die.

But of course that all pales beside the major issue, which is that this story revolves around a female character being raped and killed.

And it’s a red herring.

The things that happen to Sue in this story—her assault, her death, the mutilation of her corpse—don’t happen because of who she is. They happen because DC wanted to be cool and dark and edgy, like Marvel but better, and the way to do that was to put a rape front and center in a high profile comic.

This isn’t me extrapolating what the mindset of DC editorial was at the time, though that’s easy enough to do from their output. No, this comes from Valerie D’Orazio, who was assistant editor on Identity Crisis and has spoken a few times about the experience of working on it. It’s from her that we know DiDio’s stated goal at this point was “to take the smile out of comics.” It’s from her that we know that the genesis of the book was the editorial declaration: “We need a rape,” and that Sue Dibny was chosen because she was a “good girl,” making her assault all the more jarring. (Because “bad girls” deserve it, I guess?)

It’s from D’Orazio, too, that we know that an associate editor went running into his boss’s office, gleefully shouting that “The rape pages are in!” And that actually drawing those pages made artist Rags Morales feel ill.

It’s perhaps worth noting at this point that D’Orazio has also discussed her history of being sexually harassed by the editor on Identity Crisis (and many other books), Mike Carlin.

Given how much editorial wanted the rape plot line in there, and given how insensitive their in-house discussion of a sensitive subject was, it’s not surprising that the end product uses rape only for shock value and misdirection. It’s not a book about rape in any meaningful sense, because it’s not a book about Sue, or even about Ralph or Dr. Light. It’s a book that has a rape in it, as envisioned by grown men who think putting rape in your work is something that makes you cool and grown up, even as you giggle over it like naughty children.

And it’s a book that offers up female characters for the slaughter in service of that prurient rubbernecking: not just Sue, but Jean, who had existed for 43 years prior to this book, whose villainous turn is motivated by nothing but out-of-nowhere, unhinged clinginess, and who was permanently ruined as a character for a book that, once again, isn’t actually about her or her actions.

So what is Identity Crisis actually about? It’s about the impossibility of trusting anyone: your wife, your friends, your heroes to do the right thing. It’s about how what you thought was something beautiful and innocent—those Satellite Era comics you loved as a kid, the Dibnys’ sweet and playful marriage—is actually tainted. (Please note that I am describing the comic’s themes here and not suggesting that real rape survivors or their relationships are “tainted” by their experiences.)

I’ve always theorized that this need to break down the lighthearted comics of the past speaks to an essential insecurity on the part of the creators. Superheroes are, at the end of the day, deeply goofy at their core. For a certain kind of mindset, growing up to discover that something you thought was cool as a kid was, in fact, deeply goofy, means that the only solution is to force it to be cool, by any means possible. That toy you used to love isn’t as shiny as you thought? Break the toy. Who cares if other kids are still using it?

But there’s also historical context for Identity Crisis. In “Terrified Protectors: The Early Twenty-First Century Fear Narrative in Comic Book Superhero Stories,” Jeffrey K. Johnson situates it as a post-9/11 story, heavily influenced by the culture of fear and suspicion that developed in the United States after the 9/11 attacks:

“DC assaulted its superteam, the Justice League of America (JLA), in thoroughly disturbing ways…Numerous superheroes trade their morals and values for safety and violate the rights of other heroes and villains that disagree. No one is safe and no one can be trusted. Our heroes and their families are not who or what we thought they were and now everyone must be seen with fear and suspicion. As many Americans began to distrust those around them, so did their heroes.”

Johnson traces Identity Crisis through to its immediate fictional successor, Infinite Crisis. Like Identity Crisis, Infinite Crisis begins with the murder of a comic relief C-lister (the Ted Kord Blue Beetle, in this case) by another seemingly harmless supporting character (Maxwell Lord). Max then takes mental control of Superman and sends him on a rampage that only stops when Wonder Woman snaps Max’s neck, further alienating a horrified Batman from his allies.

Sue, Ted, and Max were all strongly associated with the lighthearted Justice League book of the late 1980s, Justice League International. By 2008, Ralph was also dead, along with three more former JLI teammates. Taking the smile out of comics, indeed.

As Johnson points out, Marvel had its own share of dark and cynical post-9/11 stories, like House of M and Civil War. DC and Marvel have been locked in a sort of arms race since the ’60s, after all, of “That worked for the other guys so let’s do it ourselves but even harder.” The spiraling downwards into violence and suspicion happened across the industry, to the detriment of everyone, and not just at DC. And it can’t just be blamed on one comic, given the political context.

But DC’s choice to base their own jumping-off point for this new wave of storytelling on a rape not only spoke to their disdain for women and rape victims, it meant that every subsequent plot development in their greater universe hinged on a throwaway rape plot point. When Batman’s suspicion of his fellow Leaguers caused him to build a spy satellite to surveil them, readers were reminded that this was the point of Identity Crisis, and not Sue Dibny’s rape, murder, and mutilation. What happened to her didn’t matter; how Batman felt about a tangential issue did.

It also made rape more speakable as a plot point and a threat, especially since Dr. Light was restored to the pantheon of competent villains. In an issue of Green Arrow that came out shortly after Identity Crisis, Dr. Light gleefully beats up the other Dr. Light—a heroic Japanese woman—then informs Green Arrow that it was almost as good as raping her would have been. The callous salaciousness of “the rape pages are in!” permeated far beyond that one moment in the DC offices.

Don’t get me wrong: sexual violence has been a part of comics since the beginning, going back to all those pinup-y covers of tied-up women menaced by sinister figures that EC and Fox Comics did such a brisk trade in. It was a truism before Identity Crisis that it was harder to find a female character who hadn’t been sexually assaulted in some way than one who had. But Identity Crisis’s aggressive handling of such sensitive subject matter paved the way for DC to continue to shout about it, over and over until its efficacy as shock value had completely dried up. (Then they moved on to dismemberment. It was a gruesome decade.)

Like I said at the beginning of this piece, there are reasons Identity Crisis succeeded. The noir tone is gripping, and after all, you can’t know that a whodunit is going to fall completely flat until you know, well, who done it. Plus, that first issue depicts Ralph and Sue’s love for one another so beautifully that it remains, in isolation and without the last couple pages or so, one of the best comics about them ever published.

Maybe it was Meltzer’s way of apologizing.

Even after DC erased the vast majority of their continuity in 2011’s New 52 reboot, they insisted that Identity Crisis was somehow still canon, despite the fact that the Justice League was a brand-new operation that couldn’t possibly have a long history full of dark secrets. Ralph and Sue Dibny remained MIA for another four years, before returning in 2015. In a world where superheroes pop in and out of the grave every week, Identity Crisis condemned them to wallow in one of DC’s darkest stories for over a decade. Even now, it’s what they’re best known for (though Ralph’s long stint on the CW’s Flash is hopefully changing that).

It was around that same time, with initiatives like DCYou and Rebirth, that DC began to ease up on its rigid editorial micromanaging. With that release came room for brighter, more optimistic stories. While there are absolutely still dark, nihilistic stories coming out of DC every month—see, oh, the entire Black Label line—it feels less like every editorial summit begins with “Give me Identity Crisis, but worse.”

Some of DC’s “dark and edgy” comics have been so influential that they’ve changed the medium permanently, with books like The Dark Knight Returns and The Killing Joke leading that list. Others cause an immediate trend, but in retrospect turn out to be more of a flash in the pan than a tectonic shift. Looking back at Identity Crisis 15 years later, now that we’re finally out of its blast radius, I think—I hope—that we can safely say it’s the latter. DC has more female creators and staff now than they did back then. They are going back to the sexual assault well far less frequently. They’re letting creators tell the stories they want instead of dictating plot lines to them. Hopefully, these are all trends that will continue.

Identity Crisis seemed at one time like a book that would go down in history as an Important Text. Now it feels like a modern relic, a product of its time creatively and culturally. For the sake of the medium, I hope we can leave it there.