Comics and The Blind: To Visualize Without Seeing

At last year’s Toronto Comic Arts Festival, I decided to do something different. Rather than just attend the two days of attending panels, and buying comics, I made the decision to start my TCAF experience a little early. The festival had some programming set up a few days before, and one of those events were The Canadian Society for the Study of Comics academic conference. The annual conference is in partnership with the festival, and it’s a place where knowledge, and research of comics across disciplines are exchanged. Most of its sessions are open to anyone who wishes to attend, and that’s what I ended up doing with friends.

On the second day of the conference, I went to a session called “Reconstructing Realities in the Comics Medium” where three people were presenting their research on realities, and their perception. There was one on Picture a Favela, and photography as well as psychiatry’s depiction in comics. What stood out to me was a presentation by University of Winnipeg’s Professor Brandon Christopher called “Can Blind People Read Comics?: The Otherness of Reading Philipp Meyer’s Life“. This had taken place weeks after Netflix’s Daredevil had just premiered, and Netflix’s announcement that an audio description option was available to blind audiences (especially since its lead character was a blind superhero).

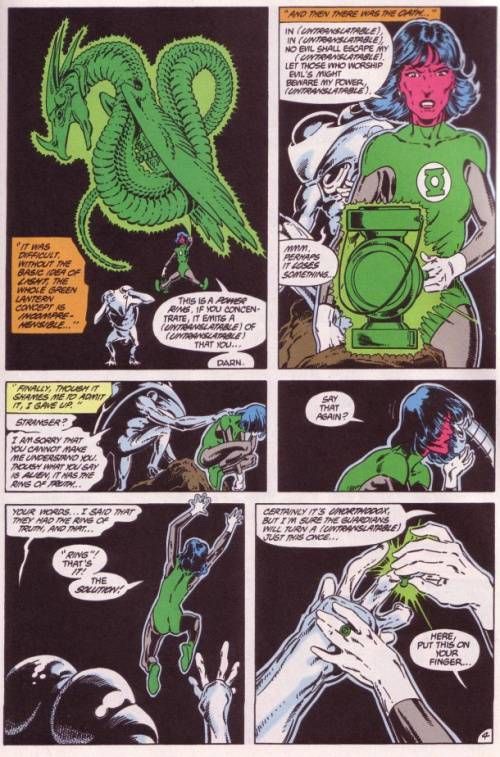

Tales of The Green Lantern Corps Annual #3. 1987

During his presentation, Professor Christopher addressed the issues we don’t think about when it concerned blind “readers” of comics by talking about Alan Moore, and Bill Willingham’s “In Blackest Night” story in the Green Lantern Corps Annual #3 (1987). A Green Lantern named Katma Tui heads into the Obsidian Deeps to recruit for the Green Lantern Corps, and finds a worthy candidate in Rot Lop Fan. Since devoid of light, its inhabitants have adapted by gaining heightened hearing, and a loss of their sight. This causes problems of communication between Katma, and Rot Lop Fan since the Green Lantern’s oath is based on language that is visually coded:

In brightest day, in blackest night,

No evil shall escape my sight.

Let those who worship evil’s might

Beware my power–Green Lantern’s light!

Eventually, Katma realizes this, and changes the oath to accommodate Rot Lop Fan.

In loudest din or hush profound,

My ears catch evil’s slightest sound.

Let those who toll out evil’s knell

Beware my power, the F-Sharp Bell!

As Professor Christopher talked about this story, I thought about how invisible something like this was to me. Never once did I think about how our language is full of visual codes, and cues. It was like that first episode of Daredevil when Karen mentioned how dark his apartment was since he, a blind man, had no use of light. Moments like these are great reminders of the privilege I held.

In the presentation, it was discussed how we could include blind comic fans into the comics experience. A straight translation of the print comic to audio was a terrible way to do it since the text box that normally sets the scene for visual readers would be read as redundant if the art is already being described for the listener (see: Daredevil #1 audio). You would have to adapt the comic to feel like it’s for blind audiences rather than the “just and stir” method. Graphic Audio does this well by creating an audio play with comics like Ms Marvel featuring more than one actor and sound affects. The redundancies are eliminated and it very much feels like a “movie in your mind” like the tagline says.

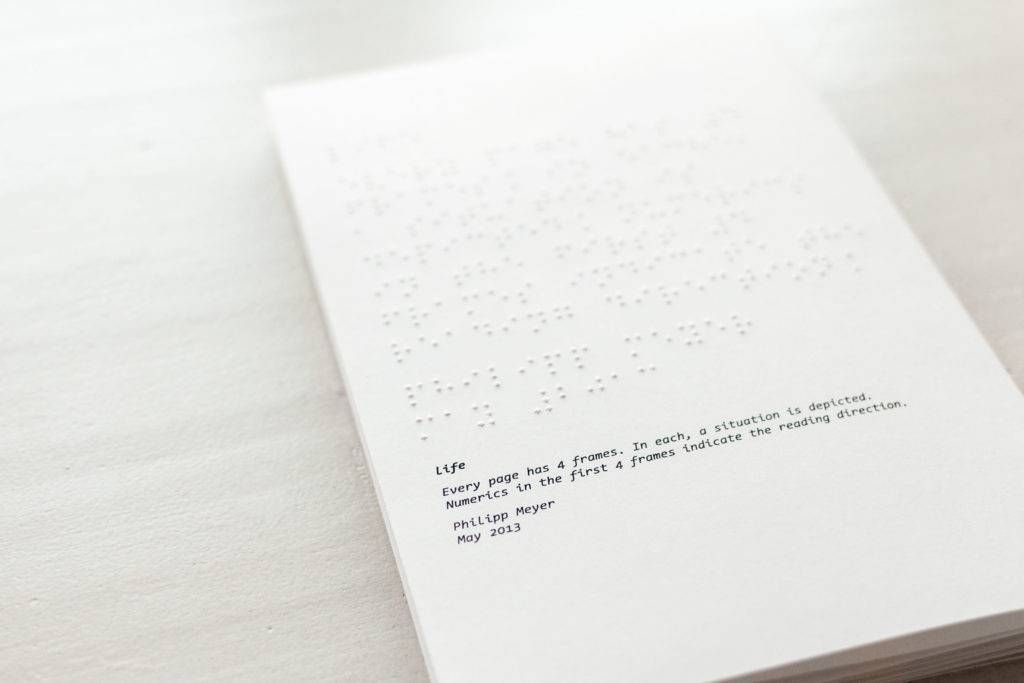

Life by Philipp Meyer

And of course, there’s Philipp Meyer’s Life which is one possible way to make tactile comics. It’s a very short comic using braille to tell its story.

During my Interaction Design studies I went half a year abroad to try something new. I took a course about comics to find out if it’s possible to create a short comic that is readable for people without eyesight. The reader should be able to follow and explore the story through touching the paper. I saw it as a challenge and a chance to fathom the possibilities of tactile storytelling.

-Philipp Meyer

I highly recommend checking out Meyer’s experience on making the comic and it’s only one possible way to make different kinds of comics for all kinds of people. I’m really glad that I got to attend that particular session, and heard Professor Brandon Christopher speak on the topic. Hopefully this is the start to open ourselves up to just beyond our field of vision own experiences.