Comics A-Z: Fairy Tales, Folktales, and Myths from Popul Vuh to Tengu

What I’m going to do in this A–Z is look at fairytales, folktales, and myths from a different direction (and a couple of different angles): I’m going to look at stories that are either western in origin that have been reimagined through other lenses, stories that were coopted and have now been retold by the people to whom they originally belonged, or upcoming stories about which I’ve noticed people voicing concerns for culturally linked reasons. There do seem to be some cross-cultural ur-stories (e.g. great floods, the taming of primordial chaos, and, oddly, vampires?) that I’m planning to stay away from since they’ve already been fed through a truly staggering number of cultural lenses. If I tend toward manga it’s because that’s what I’ve read most widely in comics originating outside of the U.S. so far, but I am actively working to widen my perspective and hey, if you have any recommendations, please send them to @BookRiot.

P: Popul Vuh

Popul Vuh: A Retelling by Ilan Stavans and Gabriela Larios

An oral tradition threatened, like so many others, by European colonization, the Popul Vuh—the Maya creation myth—was written down in the 16th century by members of the K’iche nobility in the hopes of preserving tradition. Translated into Spanish by a Dominican monk, it is one of few primary source documents that offers insight into not only foundational Latin American mythology but the Indigenous way of life destroyed by Spanish invasion and colonization. In the tale, gods and monsters are cues to the larger society’s code of ethics, beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife, and the struggle for survival in a beautiful but sometimes cruel world.

Q: Queen of Heaven

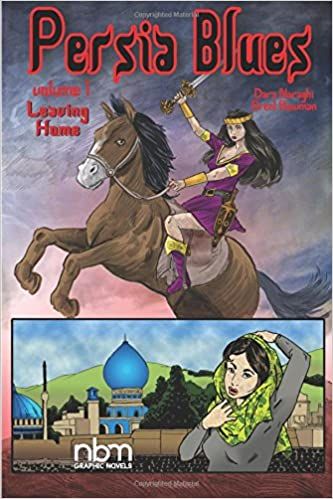

Leaving Home (Persia Blues #1) by Dara Naraghi and Brent Bowman

Many goddesses have borne the epithet “Queen of Heaven” through the ages. One of them is Anahita (the Persian incarnation of Inanna/Ishtar) who was first a goddess and later a Zoroastrian angel. Minoo Shirazi could encounter either in the imaginary kingdom to which she escapes when the constraints of modern Iran, the immigrant experience, and her demanding family, are a bit too much for her to handle.

Then again, maybe balance and peace are to be found where worlds collide…

R: Ryujin (Ryu-o)

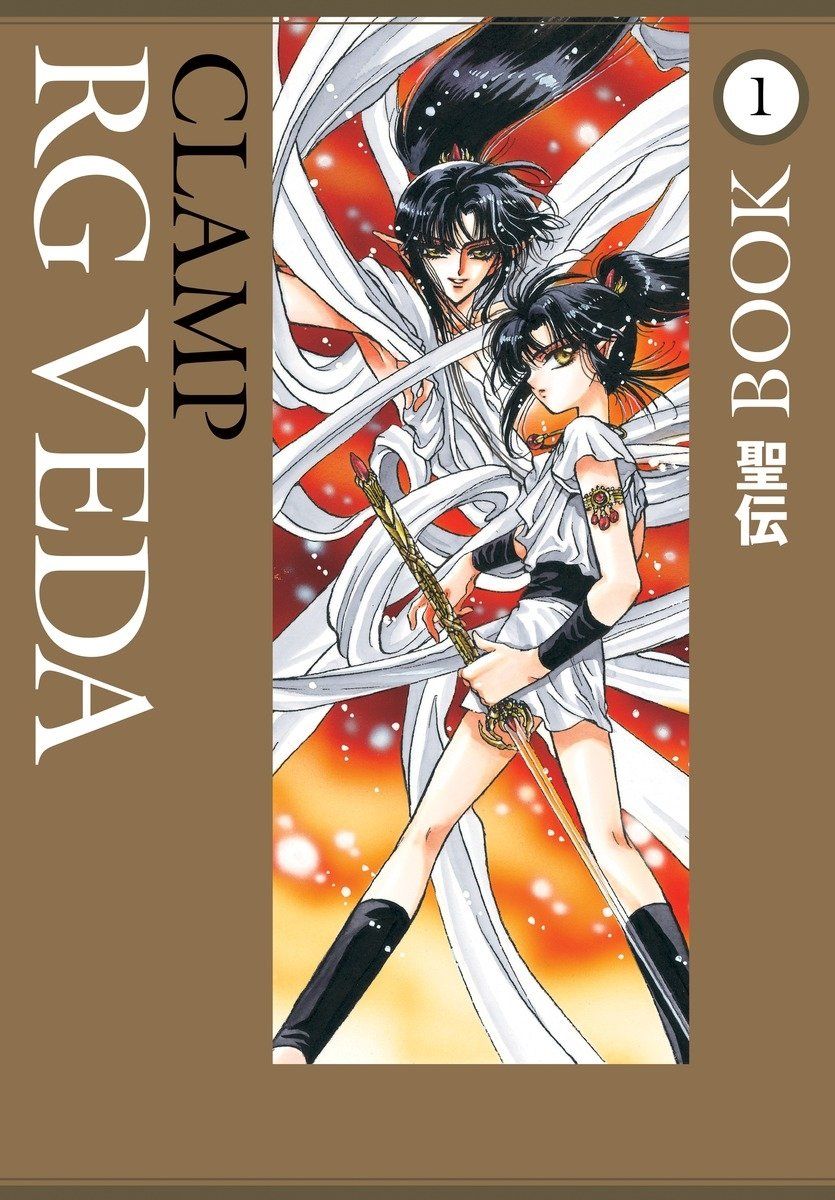

RG Veda by CLAMP

The Rig Veda is the oldest known Vedic Sanskrit text. It is considered one of the four sacred canonical texts of Hinduism.

RG Veda, CLAMP’s first traditionally published manga is, at best, very loosely based on the Rig Veda—so come for the adventure and stay for the excellent hair and sartorial decisions, but if you want a working knowledge of the Rig Veda, you’re going to need to go read the Rig Veda. What you will get in the manga, however, is a mythologically connected (and also hilarious) incarnation of the Ryujin or The Dragon King. Who is conveniently named Ryuu.

In the west, dragons are traditionally linked with hoards and fire and eating knights. In the Middle Ages, they were often stand-ins for demons or even for the Devil. In China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and some other Asian countries, however, dragons are associated with water and tend to be of more helpful and protective disposition though that’s by no means universal. Some scholars believe that the Dragon King is originally an Indian deity who was “imported” to Japan by way of China. As in India, Ryujin is a sea god and master of serpents; he represents the duality of the oceans, both its dangers and its possibilities, death by storm and medicine to be found in the waves, salt water and fresh.

In RG Veda, Ryuu must prove his worthiness to ascend to the throne by diving into primordial waters and retrieving a sword named Dragon Fang. Dragon Fang is the key to a door that keeps the sea monsters from destroying all life in the realm. After retrieving the sword, Ryuu must find another way to lock the door before returning to the surface; just as Ryujin was said to protect the island nation of Japan, so too will Ryuu protect his land from the creatures of the deep and the changeable sea.

S: Shatrughan

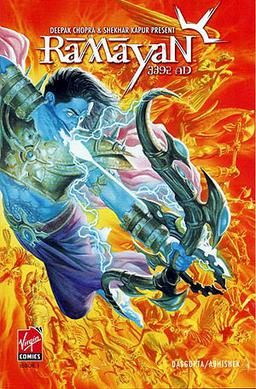

Ramayan 3392 A.D. by Shamik Dasgupta and Shekhar Kupar

All right, this one is gonna get a little weird and…I got nothing. Mythology and folklore don’t lack for “S” initiated topics, but surprisingly few of them feature in comic books or graphic novels, so we’re going to run with this spectacular cover and Rama’s godly abs.

Shatrughan features in the actual Ramayana as Rama and Lakshmana’s youngest brother. According to some he is part of Manifest Vishnu and “Shatrughan” appears as the 412th name of Vishnu in the Mahabharata.

In the comic, Shatrughan retains his place as Rama’s youngest brother and a proud, capable warrior, but they live on a continent called Aryavata, one of two land masses that still has human settlements after a nuclear holocaust. The council that rules the primary city sends Rama and Lakshmana as representatives to a peaceful region Shatrughan and a fourth brother go to quell unrest elsewhere.

Things, as so often the case in comics, go awry for everything because if things proceeded nicely, there wouldn’t be much of a story.

T: Tengu

Toritan: Birds of a Feather by Kotetsuko Yamamoto

Originally thought to take the forms of birds of prey and later evolving into human-avian hybrids, tengu (heavenly sentinels) are sometimes categorized as yōkai and other times as Shinto gods. Originally thought to be dangerous and disruptive, attitudes towards tengu have changed over time and they are now viewed by most as protective, though still dangerous, spirits who frequent mountains and forests.

While some tengu have more human appearances, others are more bird-like (think Tokoyami vs. Hawks—and if you click on that Hawks link watch out for S5 spoilers, I AM NOT KIDDING). In Toritan, Inusaki, a private detective by trade and neighborhood jack-of-all trades by necessity, can speak to and understand birds. Even so, he’s understandably confused when he finds himself crushing on a crow, and his landlady’s son, who happen to have the exact same voice…Thus far, he’s appeared as either fully human or fully crow. Will we see him in-between? What will Inusaki think if he goes full tengu? I suppose we’ll find out in March when Vol. 2 comes out…

See. It’s out there. You just have to put in the time to look. Y’all don’t have that time; that’s why you have me.

Who know’s how far we’ll go.