Childhood Adventures in Late-Night Reading

Well, everyone except his seven-year-old bookworm daughter.

“What’s wrong with this scene?” he asks. His voice is low, but it has that unmistakable parent-talking-to-a-child ring to it.

A no-brainer: it’s past midnight on a school night. I should be asleep. Mom tucked my sister and me in hours ago—but only one of us fell asleep. I don’t have to look to my right to know that my sister is lying on her bed, doing just that. Every night, I watch in awe as she rests her head on her pink-and-white monogramed pillow and falls asleep. No tossing and turning. No looking up at the glow-in-the-dark stars in the ceiling for hours. No futile attempts at counting sheep. She just sleeps—and I watch, in awe.

There is no greater magic to an insomniac like me.

“What?” I say, feigning innocence.

My defense, I decide, will consist of a simple claim: I lost track of time. Or maybe, I have to return this book at the library tomorrow. I briefly consider blaming my sister’s snoring for keeping me up. A risky plan, I decide. She doesn’t snore.

Dad gives me his signature look: a smile-and-frown, all in the same expression. (It will take me years to realize that he pulled this off by smiling with his eyes and frowning with his lips. A testament to the duality that lived inside him—presumably—since birth.)

He walks over and sits on the foot of my bed.

“I’m not sleepy,” I say, guessing that he is about to launch into a lengthy speech about how I shouldn’t be reading at this hour. (Dad is known for his lengthy speeches.)

He doesn’t reply. Instead, he smiles and gestures to the reading lamp directly above my head. It isn’t on: I didn’t want to wake up my sister.

(Fine, I’ll confess: it isn’t for my sister’s benefit—Anna sleeps like a rock on Valium. I didn’t want to get caught reading at this hour. Mom might be fast asleep, but Dad is a night owl like me.)

“You’re not a cat,” he says, leaning in and turning on the lamp. “Your eyes can’t see properly if it’s dark.”

“The night light was on,” I say.

“The nightlight is not enough.” He taps the lamp again. “If you’re going to read, keep this on. You don’t want to strain your eyes, do you?”

I shake my head. I want to ask if he’ll tell Mom—if he does, she might make me put my books away before going to bed.

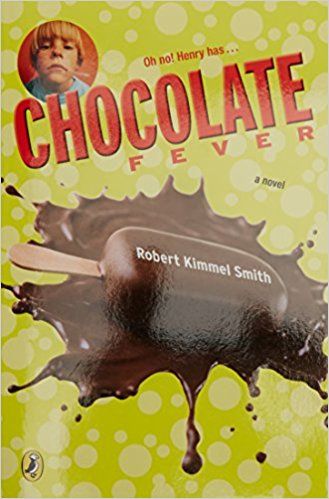

He studies the book’s cover. “Is it any good?”

“So far, yeah,” I say.

He glances over at my nightstand, where three other titles are neatly stacked: Freckle Juice by Judy Blume; Beezus and Ramona by Beverly Cleary, Sideways Stories from Wayside School by Louis Sachar. My standing record is one book per day. My school’s librarian, Ms. Beth, once asked me if I was trying to make it to The Guinness Book of World Records. I told her that if it wasn’t fiction, I wasn’t interested.

“When I was your age I had to hide my reading from my parents.” Dad’s voice is now slow and soft, like cold maple syrup making its way out of a glass jar. “I’d cover myself with three blankets and turn on a flashlight.”

“Did your parents ever catch you?”

His dark eyes shine with mischievous pride. “Never.”

I giggle, giddily sharing his triumph.

“Good night, paçoquinha.” He kisses my forehead.

“Good night, Dad.”

As he makes his way out of the room, I wait for him to tell me to put the book away and go to sleep.

He does no such thing.

The next day, Dad asks me if I’ve checked out a book from the library.

I nod. Mom is only a few feet away, talking on the phone. I wonder if he’s told her about my late-night reading. I want to ask him not to, but I don’t. I open my backpack and show him a copy of The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes.

That night, I open that book and find a small piece of paper inside it, one that wasn’t there when Ms. Beth handed it to me hours before.

Remember: you’re not a cat. Turn the light on.

Don’t strain your eyes.

Love, Dad

I turn on my lamp to read.

I turn it on again the next day, and the day after that. And every time my fingers touch the switch, I smile and think of Dad.

It will be many years before I think of this day again and, when I do, I will realize that my dad wasn’t just looking out for my eyesight (or keeping a secret from my mom). He was endorsing my love of late-night reading, of losing myself in fiction, of books. It is a love I passed on to my sister. A love that fed my imagination, elevated my childhood, guided me into adolescence and adulthood. A love that provides me with both empathy and escape. A love that has allowed me to meet some of my best friends. A love that has shaped my career, my marriage, my life.

A love that defines me till this day.

My dad is no longer on this Earth. But every time I read at night, I turn on a light (be it an actual reading light or my iPad’s night light). And I feel him there with me.

And I thank him.

Thank you, Dad.