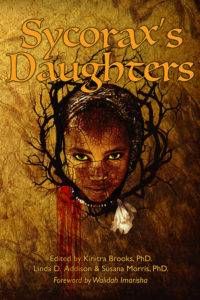

Celebrate Women in Horror Month with 41 Black Women Writers

Fear of the Darkness

I was afraid of the dark as a little kid because I saw the monsters more clearly with the lights out. In middle school, reading Stephen King helped me master my fears. In adulthood, I found horror less interesting. Few writers seemed to be covering new territory, I didn’t understand what was sexy about vampires, and the genre moved toward an embrace of torture porn and away from the supernatural splendor that had drawn me in in the first place.

Last year I met Linda Addison at the Tucson Festival of Books. Her award-winning collection of horror poetry and short fiction, How to Recognize a Demon Has Become Your Friend, reminded me that there are other voices, and other ways of reading familiar tropes. So, when Addison mentioned that she had co-edited an anthology of short horror stories and poetry written entirely by black women, I was excited for her fresh perspective.

In Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Caliban, son of the Algerian sorceress Sycorax, is enslaved, but his male voice remains, to curse, to argue, to beg forgiveness. Sycorax, dead by Prospero’s hands long before the story begins, cannot speak.

Sycorax’s Daughters summons the silenced voice.

“This nation holds that Blackness, and therefore Black people, are the ultimate horror,” writes Walidah Imarisha in her foreword. The evening news is rife with cultural bias conflating blackness with monstrosity, even as the Black experience of “gentrification, white supremacists, brutal cops, and…slavery” makes the most brutal supernatural horror tropes appear “almost banal.” Many stories in the collection cast the Black female protagonist in a role that, from the outside, seem to mark her as the monster, even as her experience of the world has dictated her response.

Lessons from Many Voices

Shakespeare stole Sycorax’s point of view from the world. Sycorax’s Daughters draws that perspective to the fore, allowing Black women to explain themselves, and the evils they have experienced, to the delight of readers who are ready to hear.

The interstitial horror poetry creates and evocative refrain, a rich tapestry of unexpected voices. Horror poetry as a category doesn’t seem to receive a lot of exposure. In fact, the day that I first met Linda Addison, a mutual friend had been explaining her work right before we bumped into her. My reaction was, “Horror poetry? I guess I read ‘The Fungi from Yuggoth’ by HP Lovecraft.” Then she was standing in front of me, laughing, and offering her perspective on the state of the genre.

These poetic voices can even conjure terrifying atmospheres without resorting to supernatural fear. Pretty often, the poets featured in Sycorax’s Daughters show how the real world offers sufficient dread.

The prose voices also provide surprises and reversals. In “The Monster” by Crystal Conner, a seasoned combat veteran finds herself making an unlikely alliance with white supremacists because the entity chasing her is even scarier than Nazis. Cultural appropriation takes the shape of an unassuming but real monster in Nicole D. Sconiers’s “Kim.” In my favorite story in this collection, “Letty,” by Regina N. Bradley, Gris is visited by a psychopomp—a strange, female, winged vision—who tells a slave narrative that embodies true horror.

Throughout the stories, injustice piles on injustice. Often, all efforts at restoring a measure of equality result in…further injustice. It’s a Kafkaesque hopelessness, the terror of a world without logic or meaning. It’s a world that many of the authors in this anthology know all too well.

Our Bodies

Imarisha’s point concerning the horror genre and life in a Black female body is drawn over and over. In the future world of “Of Sound Mind and Body,” by K. Ceres Wright, Dara has signed away agency to her own body, but the horror she experiences in life palls in comparison to the clause in her contract covering death. In “Ma Laja,” by Tracey Baptiste and “Summer Skin,” by Zin E. Rocklyn, women are thrust into the role of the monster just to survive.

Throughout this book, we also see strength in the face of hopelessness, women who keep plodding forward in the face of impossible adversity. Akasha in “The Mankana-kil” by L. Penelope summons her own demons in response to the discrimination she faces as one of two students of color in her school. “Taking the Good,” by Dana Mcknight features the historic monster Lamia saving Helene from her unloving lover.

Sycorax’s daughters—the Black sorceresses working to protect themselves, their homes, their families—appear time and again throughout the book: weird women casting spells in swamps, urban witches crafting their own incantations in the heart of the city. They are children, they are elderly, they are ageless.

February is Women in Horror Month and I can’t think of a better way to celebrate than with Sycorax’s Daughters.